In looking at the history of Combe Down one, inevitably, has to look at the history of Bath 1700 – 1764.

Bath today is very well known, a UNESCO World Heritage site known for its natural hot springs and 18th century Georgian architecture.

TripAdvisor describes it thus:

“Known for its restorative wonders, Bath was once the home of Jane Austen. Sure, you could attempt to conjure up this elegant city by reading Pride and Prejudice in your tub, but as Bath has a lot more history than your bathroom (we assume, anyway) you’d be missing out. A stroll through Bath is like visiting an open-air museum, with roughly 5,000 buildings in the city drawing notice for their architectural merit. After your stroll, soak in the natural hot waters of the Thermae Bath Spa, once a favourite of the Celts and Romans.”

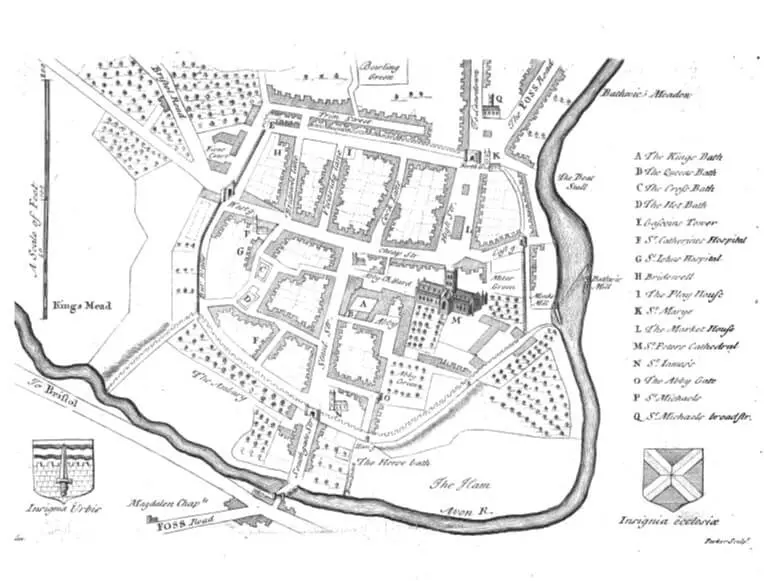

However, it was not always like this. Before the ambitions of John Wood, the Elder (1704-1754) and Ralph Allen (1693-1764) to change the medieval city of Bath into one of the world’s most beautiful cities combining Palladian architecture and landscape harmoniously William Stukeley (1687 – 1765) described Bath, in Itinerarium curiosum; or, An account of the antiquities, and remarkable curiosities in nature or art, observed in travels through Great Britain: Volume 1, so: “The small compass of the city has made the inhabitants crowd up the streets to an unseemly and inconvenient narrowness: it is handsomely built, mostly of new stone, which is very white and good; a disgrace to the architects they have there”.

He also includes a map which is shown below.

Of course, Bath had first been a Roman city and after they left was probably both in the hands of the Romano British and the Anglo Saxons until the town became Saxon controlled after the Battle of Deorham in 577.

Bath became a religious centre in 675 when a convent was established and later a monastery, the church of which grew to become Bath Abbey.

After the Norman conquest Bath remained a religious centre with the Abbey becoming the seat of the Bishop in 1157 which was confirmed by a Charter in 1256 from Henry II.

During this period Bath also became a centre of the wool trade and became famous for broadcloth.

Bath Abbey still dominated the town and its development until the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII with Bath being dissolved in 1539.

In 1552 a Charter granted the Mayor and citizens of Bath all property previously owned by the Priory in the city.

Elizabeth I authorized a nationwide collection over seven years to pay for reroofing and reglazing Bath Abbey in 1573 and also decreed that the Abbey should become the Parish Church of the City, causing the closure of all the other churches within the city boundary and thus Bath has no medieval churches.

Elizabeth I also granted the Charter of Incorporation in 1590 so that Bath became a city.

The loss of the monastery and the decline of the wool trade meant that Bath had to find another way to earn its living and tourism seemed to be something the city could do by using its Roman Baths’ heritage and the thermal springs.

The King’s Bath was improved in 1578 and 1624.

The New Bath was built in 1576 to provide better facilities and then renamed Queen’s Bath after Queen Anne of Denmark (wife of James I) visited in 1613 and 1615.

Though times were not always good, especially during the Civil War when the city was looted royal patronage continued to increase the reputation of the city. Charles II brought his wife, Catherine of Braganza in the hoping that this would produce his first legitimate heir.

Mary of Modena, wife of James II, visited Bath in 1687 needing an heir to the throne, and following her visit gave birth to a son – The Old Pretender.

During all this time, Bath never had a population greater than 3,000 and was surrounded by it’s medieval city walls. (There’s a walk that allows you to see them). The population of Bath was to rise to 28,000 by 1801 and 57,000 by 1831.

Ralph Allen became postmaster in Bath in 1712.

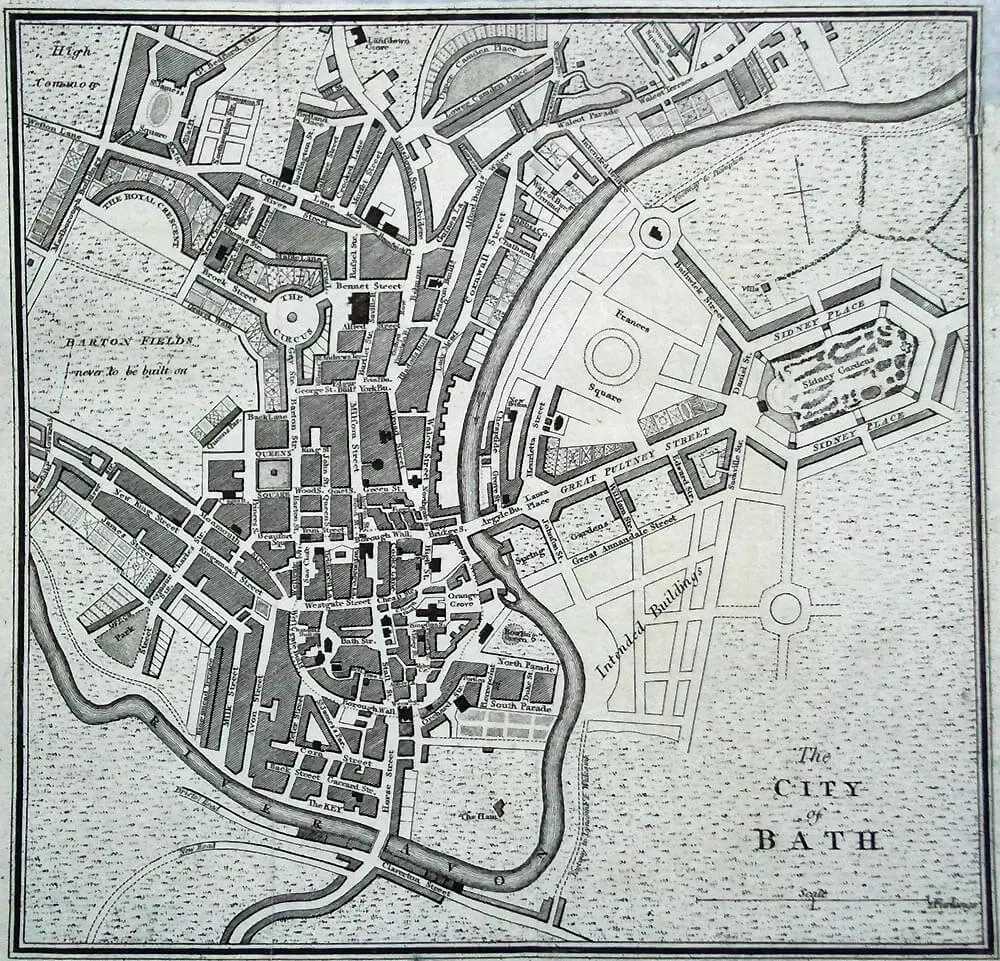

By 1726 his contract with the Post Office to run the cross and bye posts for the country had given him the contacts, confidence and cash to acquire the quarries on Combe Down, probably having seen John Wood, the Elder’s plans of 1725 for Bath which developed the town outside the existing city walls and their constrictions and restrictions.

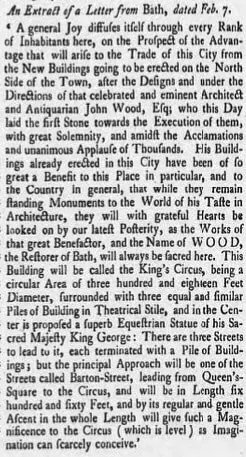

Over the next 40 years the stone from Ralph Allen’s quarries on Combe Down and Wood’s developments such as St John’s Hospital (1727–28), Queen Square (1728–36), Prior Park (1734–41), The Royal Mineral Water Hospital (1738–42), North Parade (1740), South Parade (1743–48) and The Circus (1754–68) transformed Bath from the medieval to a modern and beautiful city.