Timeline of Somerset history

Key dates in the history of Somerset

- 43–47 – Roman invasion and occupation

- 491 – Battle of Mons Badonicus (may have been fought in Somerset) (uncertain date)

- 537 – Battle of Camlann (sometimes located at Queen Camel) (uncertain date)

- 577 – Battle of Deorham (Dyrham, Gloucestershire) – Saxons occupied Bath

- 658 – Battle of Peonnum (Penselwood ?) – Saxons then occupied most of Somerset

- 710 – Battle of Llongborth (? Langport)

- 845 – First documentary reference to "Somersæte"

- 878 – Battle of Cynwit – Saxon victory over the Danes by Ealdorman Odda

- 878 – Battle of Ethandun – West Saxon victory over the Danes (uncertain whether in Somerset or Wiltshire)

- 878 – Treaty of Wedmore – after defeat of Danes by King Alfred the Great

- c900 – Kings of Wessex hold court at Cheddar

- 973 – King Edgar of England crowned at Bath

- 988 – St Dunstan buried at Glastonbury

- 1013 – Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard received submission of western thegns at Bath

- 1088 – Siege of Ilchester

- 1191 – Discovery of "King Arthur's" tomb at Glastonbury

- 1497 – Perkin Warbeck's rebellion supported by Somerset men

- 1643 – Battle of Lansdowne

- 1645 – Siege of Taunton during the English Civil War

- 1685 – Battle of Sedgemoor – Duke of Monmouth defeated

- 1685 – Judge Jeffries holds the "Bloody Assizes" at Taunton

- 1770 – Start of major enclosures of Somerset Levels

- 1805 – Somerset Coal Canal Opened

- 1827 – Bridgwater and Taunton Canal opened

- 1875 – Formation of Somerset County Cricket Club

- 1898 – County boundaries altered

- 1956 – Chew Valley Lake opened by Queen Elizabeth II

- 1974 – Formation of County of Avon, reducing the area of the County of Somerset

- 1996 – Abolition of the County of Avon, creating the unitary authorities of North Somerset and Bath and North East Somerset

Timeline of Bath, Somerset

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Bath, Somerset, England.

| History of England |

|---|

|

|

|

Prehistory

- Mesolithic – Human activity on Bathampton Down.

- Iron Age – Hillfort on Bathampton Down.[1]

- 863 BC (traditional date) – In legend, King Bladud discovers the sacred spring at Bath.[2]

1st to 5th centuries

- c. 60s – First Roman temple structures built, around the hot water springs; completed by 76.

- 2nd century

- Early: Baths extended.

- Late: Baths vaulted.

- 3rd century – By this time, Bath city walls are built for defence.

- 300–350 – Evidence for Christians in Bath.

- 5th century – Following the end of Roman rule in Britain, Bath is largely abandoned.

6th to 10th centuries

- 516 – Battle of Badon: A famous battle against the Saxons, where a progenitor of King Arthur is said to have been victorious; perhaps on Bathampton Down.

- 577 – Battle of Deorham: Bath is captured by the Saxons[3] and, being north of the River Avon, then falls within the Saxon petty-kingdom of the Hwicce.

- 628 – Following the Battle of Cirencester, the Hwicce come under the rule of the kingdom of Mercia.

- 676 – Abbess Berta founds a convent under the protection of Osric, king of the Hwicce.

- 757 – Cynewulf of Wessex grants land in Bath to monks of St Peter.[clarification needed]

- 781 – Offa of Mercia takes control of the monastery from the Bishop of Worcester.

- 878 – Bath becomes a royal borough (burh) of Alfred the Great, in his kingdom of Wessex (and also in the county of Somerset).[3]

- c. 900 – Market active.[4]

- 973 – 11 May (Whitsunday): Edgar, King of England 959–975, is crowned and anointed with his wife Ælfthryth at Bath Abbey by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury.[5] The Church of St Swithin, Walcot, is founded at about this date.

- c. 980 – Ælfheah becomes abbot of Bath.

11th to 17th centuries

- 1087 – Town, Abbey and mint pass to John of Tours.

- 1090 – John of Tours, Bishop of Wells, moves the episcopal seat to Bath, giving it city status.

- Early 12th century? – King's Bath built.

- 1102 – Bath fair active.[4]

- 1137 – Major fire.[6]

- 1148–1161 – Abbey consecrated between these dates.[6]

- c. 1174 – St John's Hospital founded.

- 1273 – Old Bridge extant.

- 1285 – Church of St Michael's Within built in St John's Hospital.

- c. 1333 – Monks of the abbey establish a weaving trade in Broad Street.[7]

- 1371 – Market mentioned in charter.

- c. 1435 – Hospital of St Catherine established.

- 1482 – "Sally Lunn's House" built.

- c. 1495 – St Mary Magdalen, Holloway, built as a chapel to a leper's hospital.[6]

- 1499 – Abbey found derelict by Oliver King, Bishop of Bath and Wells, who begins its reconstruction.[8]

- 1533 – Rebuilding of Abbey substantially completed by this date.[6]

- 1539 – January: Dissolution of the Monasteries: Abbey surrendered.

- 1552

- King Edward's School founded as a grammar school.[9]

- Approximate date: First market house built.

- 1572

- The roofless Abbey is given to the corporation of Bath[6] for restoration as a parish church.

- Dr. John Jones makes the first public endorsement of the medicinal properties of the city's water.

- 1576 – Queen's Bath built.

- 1578 – Drinking fountain installed in the Baths.

- 1590 – Bath chartered (city status confirmed) by Elizabeth I.[10]

- 1597 – Deserving poor given free use of the mineral water.[11]

- 1608 – Bellott's Hospital established.

- 1613 and 1615 - Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI and I, visits Bath for her health

- 1616 – Abbey Church consecrated.[12]

- 1625–1628 – Guildhall rebuilt.[13]

- 1643 – 5 July: Battle of Lansdowne fought near the city.

- 1657 – Regular coach service from London.

- 1676 – Dr. Thomas Guidott publishes A discourse of Bathe, and the hot waters there. Also, Some Enquiries into the Nature of the water, the first published account of the medicinal properties of the city's water.

- 1677 – West Gate pub in business.

- 1680 – Supposed origin of the Sally Lunn bun.

- 1687 – Mary of Modena, queen consort of James II of England, visits in the hope that Bath waters would aid conception; by the end of the year she is pregnant with James Francis Edward Stuart.

1700s

- 1702–1703 – Queen Anne visits.

- 1704 – First pump-room built;[14] Richard "Beau" Nash is appointed Master of Ceremonies.

- 1705 – First theatre in the city built.[13]

- 1707 – Bath Turnpike Trust established.[15]

- 1708 – Harrison's Assembly Rooms, with a riverside walk, open.

- 1711 – Bluecoat school founded as a charity.[7]

- 1712 – March: Ralph Allen appointed postmaster.

- 1715 – Church of St Michael's Within in St John's Hospital rebuilt to the design of William Killigrew.

- 1720 – Ralph Allen begins to farm the Cross and Bye Posts in the south west of England.

- 1717 – Approximate date: Green Street developed.[16]

- 1721 – Bluecoat school opens.[9]

- 1724 – James Leake (bookseller) in business.[17][18]

- 1725–1727 – Guildhall extended.

- 1725

- John Wood, the Elder, newly returned to Bath, presents his plans for the city to Ralph Allen.[7]

- Approximate date: William Oliver (physician) settles in Bath.

- 1726

- Ralph Allen begins buying up Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines for building stone.[7]

- James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, buys Chandos House to let as lodgings.

- 1727–1728 – John Wood, the Elder, executes his first private commission in Bath, a new building for St John's Hospital.[9]

- 1727–1736 – Beaufort Square laid out by John Strahan.[19][20]

- 1727

- Gilt bronze head from cult statue of Sulis Minerva from the Roman Temple is found by workmen excavating a sewer and placed in the guildhall.

- 15 December: River Avon made navigable downstream to Bristol.

- Approximate date: Construction of Ralph Allen's Town House begins.

- 1728

- St John's Gate ("Trim Bridge") built.[7]

- First Bath Racecourse recorded.[21]

- 1728–1736 – Queen Square laid out by John Wood, the Elder.[7]

- 1730s – Parade Gardens laid out.

- 1731 – A tramroad is opened to carry building stone from Ralph Allen's Combe Down mine through his Prior Park estate down to the Kennet and Avon Canal.

- c. 1733

- Thomas Warr Attwood becomes de facto first Bath City Surveyor and Bath City Architect.

- First printing press established in the city, by Felix Farley of Bristol.

- 1734

- Royal visit by William IV, Prince of Orange,[10] marked by an obelisk of 1735.

- Construction begins on Ralph Allen's house at Prior Park to the design of John Wood, the Elder.

- 25 December: St Mary the Virgin opened near Queen Square as the city's first proprietary chapel (foundation stone laid 25 March 1732; designed by John Wood, the Elder).[13]

- 1735

- Construction of New Bridge to carry the Bristol Road over the Avon begins.

- Gay Street laid out by John Wood, the Elder.[7]

- 1738 – Royal visit by Frederick, Prince of Wales with Princess Augusta, marked by erection of an obelisk in Queen Square.[10]

- 1739

- Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases (Royal Mineral Water Hospital, "The Min") established by Act of Parliament as The Hospital or Infirmary in the City of Bath; it will be built to plans of 1738 by John Wood, the Elder.[11]

- Portrait painter William Hoare settles in Bath.

- c. 1741 – North Parade built by John Wood, the Elder.

- 1742

- Ralph Allen elected mayor and his residence at Prior Park is completed.[16]

- Church of St Swithin, Walcot, rebuilt following storm damage in 1739.

- William Frederick (bookseller) in business.[17]

- 1743–1749 – South Parade built to the design of John Wood, the Elder.[7]

- 1744

- 27 February: The Bath Journal, the city's first newspaper and a predecessor of the Bath Chronicle, begins publication.

- Sham bridge in Ralph Allen's Prior Park Landscape Garden estate designed by Alexander Pope.[22]

- 1745 – Beau Nash forced to retire as Master of Ceremonies due to anti-gambling laws.[7]

- 1747 – Bath Pauper Scheme originates.

- 1750

- 27 October: Old Orchard Street Theatre opens as St James' Theatre.[23]

- Approximate date: Bath Oliver biscuit devised by William Oliver (physician).

- 1751 – Pump Room enlarged, truncating the King's Bath.

- 1752 – King Edward's School rebuilt in Broad Street.

- 1754

- February: The Circus house construction begins to the design of John Wood, the Elder.[24]

- Old Bridge rebuilt.

- 1754–1755 – North and South Gates demolished (West Gate demolished c. 1776).

- 1755

- Bath Advertiser newspaper begins publication.[25]

- Roman Bath rediscovered.[26][27]

- Kingston Baths built for Evelyn Pierrepont, 2nd Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull on the site of the Abbey cloister.

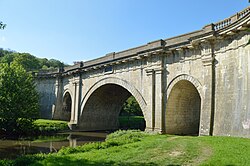

- Palladian bridge in Ralph Allen's Prior Park Landscape Garden built to a design by Richard Jones.[22]

- 1758–1774 – Portrait painter Thomas Gainsborough resident at 17 The Circus.[19]

- 1759 – William Pitt, Secretary of State, from 7 The Circus, orders James Wolfe to capture Quebec City.[19]

- 1760 – Gay Street developed.[28]

- 1762 – Sham castle built as an eye-catcher in Ralph Allen's Prior Park Landscape Garden to a design by Richard Jones.[22]

- 1762–1763 – Milsom Street built.

- 1765 – 6 October: The second chapel of the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion is opened in The Paragon; George Whitefield is the first preacher.

- 1766

- Christopher Anstey publishes his long satirical epistolary poem The New Bath Guide.

- Astronomer William Herschel arrives in Bath, initially as organist of the Octagon Chapel (completed 1767); his house in New King Street is built.

- 20 December: Royal Crescent house construction begins to the design of John Wood, the Younger.

- 1767–1768 – Brock Street built to the design of John Wood, the Younger.

- 1768 – The Theatre Royal, Bath (Old Orchard Street Theatre) and Theatre Royal, Norwich, assume these titles having been granted Royal Patents, making them officially England's only legal provincial theatres.[29]

- 1769 – The Circus ("King's Circus") houses completed to the design of John Wood, the Younger.[19]

- 1769–1774 – Pulteney Bridge constructed to the design of Robert Adam.[28][19]

- 1771 – 30 September: New (Upper) Assembly Rooms, built to the design of John Wood, the Younger, open with Capt. William Wade as Master of Ceremonies.[9]

- 1772 – 18 March: Playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan elopes with soprano Elizabeth Ann Linley from her home in Royal Crescent.[19]

- 1774 – Royal Crescent houses completed to the design of John Wood, the Younger.

- 1775–1777 – Hot Bath built to the design of John Wood, the Younger.[7]

- 1775 – 15 November: Architect Thomas Warr Attwood is killed by the collapse of a derelict building which he is inspecting on the site of the intended new Guildhall and is succeeded as Bath City Surveyor by Thomas Baldwin.

- 1777–1779 – Wesleyan church built in New King Street.[19]

- 1777

- 28 August: Society for the Encouragement of Agriculture, Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce founded.[30]

- Church of St Swithin, Walcot, rebuilt to the design of John Palmer, opens.

- Card room added to the Assembly Rooms.

- Real tennis court opens in Julian Road.[31]

- 1778–1782 – Sarah Siddons appears at the Old Orchard Street Theatre.

- 1778 – New Guildhall completed to the design of Thomas Baldwin and the previous one is demolished.

- 1779 – 28 December: Bath Philosophical Society founded; ceases 1787.[32]

- 1780

- 13 June: Anti-Catholic unrest.[26]

- Roman Great Bath rediscovered.[27]

- First record of the Sally Lunn bun.[33]

- Approximate date: Oxford Row built.[16]

- 1781 – 13 March: William Herschel makes the first observation of the planet Uranus from his back garden in New King Street.[34]

- 1783–1784 – Cross Bath built by Thomas Baldwin.[35]

- 1784 – 2 August: John Palmer demonstrates his mail coach system.

- 1787–1788 – Camden Crescent built by John Eveleigh.

- 1788–1794 – Laura Place built by Thomas Baldwin and John Eveleigh.[36]

- 1788 – Bath Casualty Hospital (a predecessor of the Royal United Hospital) opens.

- 1789–1793 – Lansdown Crescent built by John Palmer.

- 1789

- July: Bath Improvement Act 1789 (29 Geo. 3. c. 73) passed by Parliament giving the city council powers to purchase, demolish and rebuild.

- South Colonnade for Grand Pump Room scheme completed by Thomas Baldwin.[37]

- Congregational church opened in Argyle Street.

- 1790

- 9 April: Thomas Baldwin is appointed first architect and surveyor to the Improvement Commissioners formed under the Act of 1789.[16]

- North Colonnade for Grand Pump Room scheme completed by Thomas Baldwin.[38]

- Roman temple pediment discovered during work near the Baths.[39]

- Somerset Place construction begins to the design of John Eveleigh.

- 1791 – 31 March: Bath Street construction begins to the design of Thomas Baldwin.[40]

- 1792

- March: Norfolk Crescent construction begins to the design of John Palmer.

- Bath City Dispensary and Infirmary founded.

- Lansdown Course races begin.[41]

- 1793

- September: Laying out of Sydney Gardens begins to the design of Thomas Baldwin.

- Bath bank crash.

- 1795

- 11 May: Sydney Gardens open as Bath Vauxhall Gardens, commercial pleasure grounds. Sydney Hotel is under construction here.

- 28 December: Grand Pump Room opens.[42] Begun around 1789 by Thomas Baldwin,[7] construction work is completed 1793–1799 by John Palmer.[9]

- Harmonic Society formed.[43]

- 1796? – York Street opened.

- 1797–1798 – Cross Bath rebuilt by John Palmer.[7]

- 1797

- 30 May: Abolitionist William Wilberforce marries Barbara Spooner at the Church of St Swithin, Walcot, the couple having met on 15 April in Bath.

- House of Antiquities opened to display archaeological finds.

- 1798 – 7 November: Christ Church dedicated as a proprietary chapel built to the design of John Palmer.

- 1799

- By summer: William Smith produces the first large-scale geological map, of the area round Bath.[44]

- 8 August: Lace goes missing from Elizabeth Gregory's milliner's shop; Jane Leigh Perrot (Jane Austen's aunt) is charged with its theft.[45]

- 11 December: William Smith draws up a table of strata round Bath.[44]

- Sydney Hotel opens in Sydney Gardens to the design of Charles Harcourt Masters.

- A new Philosophical Society is established.[9]

1800s

- 1800

- North side of Pulteney Bridge collapses in a flood.

- S. W. Simms (bookseller) in business.[46]

- Approximate date:

- Jewish congregation formed.[47]

- First houses in Sydney Place completed to the design of Thomas Baldwin.

- 1801

- January: Jane Austen becomes resident in Bath when her father retires here; she will remain until summer 1806 living mostly in the new-built Sydney Place.

- 1 May: Kennet and Avon Canal opens from Bath to Devizes[48] (completion of the locks at the latter place at the end of 1810 creates through inland water communication to London).[49]

- 1802 – Balloon ascents from Sydney Gardens.

- 1805

- 1 January: Jane Austen's father, the Rev. George Austen, dies in Bath; he is buried at the Church of St Swithin, Walcot, where he had been married in 1764

- Penitentiary established.[9]

- New Theatre Royal[9] (replacing the Old Orchard Street Theatre) and Barker's Picture Gallery open.[50]

- De Montalt Mill, Combe Down, established as a paper mill.[15]

- 1806 – East wing of Grand Pump Room completed.[16]

- 1808 – New houses in Sydney Place completed to the design of John Pinch the elder.

- 1810

- Lancasterian Free School established.[50]

- Union Street completed.

- 1812 – Jewish Burial Ground, Combe Down opened.

- 1813 - Claverton Pumping Station opens, allowing the Bath locks on the Kennet and Avon Canal to be used in periods of low rainfall.

- 1815

- Cleveland Pools opened.[51]

- Stothert's iron foundry established.[15]

- 1816 – 8 January: Third Bath Philosophical Society formed.[52]

- 1817

- Royal visit by Queen Charlotte.

- Atkinson & Tucker (booksellers) in business.[46]

- 1818 – Bath Gas Light Company established.[15]

- 1819 – Masonic Hall dedicated.[50]

- 1821 – 6 February: Original Assembly Rooms in Terrace Walk destroyed by fire.

- 1822

- Norfolk Crescent completed to the design of John Pinch the elder.

- Post office in Broad Street.

- 1824 – Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution founded (given Royal status 1837).[53]

- 1825

- 19 January: Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution opens its premises on the site of the original Assembly Rooms in Terrace Walk.

- The Corridor, one of the world's earliest retail arcades, is built to the design of architect Henry Goodridge.[7]

- Mechanics Institute opens.[43]

- Lansdown Cricket Club formed.

- 1826

- Bath United Hospital opens in Beau Street in a building designed by John Pinch the elder.

- A. H. Hale's pharmacy in business in Argyle Street.

- 1827

- Beckford's Tower (Lansdown Tower) is completed by Henry Goodridge for William Beckford.

- Cleveland Bridge opened as a toll bridge.[54]

- John Loudon McAdam appointed Surveyor of the Bath Roads, a post which he holds until his death in 1836.[15]

- Partis College completed as almshouses for women by Ann and Fletcher Partis.[16]

- 1829 – New basin at baths completed.[16]

- 1830

- Victoria Park is opened by the 11-year-old Princess Victoria as a private pleasure ground.[55]

- Prior Park College is opened as the Sacred Heart College.

- 1831 – Jolly's department store opens as The Bath Emporium.

- 1832 – Sydney Buildings constructed.[16]

- 1833–1834 – George Phillips Manners restores the Abbey, replacing the pinnacles.[6]

- 1834–1837 – St Michael's Without church rebuilt to the design of George Phillips Manners.

- 1834 – Stothert, Rayne & Pitt acquire the Newark Iron Foundry.

- 1836

- 1 January: Local government reformed under terms of the Municipal Corporations Act 1835; city corporation is obliged to surrender control over Abbey appointments.

- 28 March: Bath Poor Law Union formed and begins construction of a new workhouse at Combe Down.

- 30 May: Major fire at Prior Park.

- North Parade Bridge built in cast iron to the design of William Tierney Clark and Victoria suspension bridge built to the patent of James Dredge, Sr.

- 1837 – Victoria Column erected.[56]

- 1839 – Isaac Pitman moves to Bath.

- 1840

- 2 May: First Penny Black postage stamp sent from 8 Broad Street by Thomas Musgrave.

- 6 June: Novelist Fanny Burney dies in Bath; she is buried at the Church of St Swithin, Walcot.

- 31 August: Great Western Railway opened from Bath to Bristol Temple Meads; 30 June 1841 through to London Paddington.

- 1841

- January: Major floods.

- November: First "Daguerreotype Institute" (photographic studio) in Bath opened, in Subscription Walk Gardens.[52]

- 1846 – City authorised to provide drinking water from springs at Bathampton and Batheaston.

- 1847 – Commercial Reading Room and Tottenham Library founded.[43]

- 1851 – Kingswood School moves to Bath.

- 1852 – Bath School of Art founded.

- 1854 – Post Office in York Buildings, George Street (1750s).

- 1855

- February: Bath Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club established by Leonard Jenyns.[52]

- Bath Quartet Society established.[41]

- Corn market built in Walcot Street.

- 1856 – J. B. Bowler, engineer and carbonated drink manufacturer, in business.

- 1859–1860 – New Bluecoat school built.

- 1861–1863 – St John the Evangelist Roman Catholic Church in South Parade is built to the design of Charles Francis Hansom.

- 1861 – Guildhall Market built.

- 1862 – 18 April: A major fire causes the Theatre Royal to be rebuilt.[57]

- 1863 – Widcombe ("Halfpenny") footbridge first built over the Avon in wood.

- 1864

- Bath United Hospital given its Royal prefix on opening of its Albert wing.

- Locksbrook Cemetery opens as Walcot Cemetery.

- 1865

- Bath Rugby founded by members of Lansdown Cricket Club as Bath Football Club.

- Old Orchard Street Theatre becomes a Masonic Hall.[23]

- 1867

- Alexander Graham Bell rigs up a telegraph line in Bennett Street while teaching at Somerset College.[52]

- James Irvine records remains of the Roman temple of Sulis Minerva.

- 1869–1885 – Excavations of Roman Baths by Maj. C. E. Davis, the city architect.

- 1869

- 4 August: Queen Square station opens to passengers as terminus of the Midland Railway's Mangotsfield and Bath Branch Line.

- Original White Horse Inn (opposite the Pump Room) is demolished.

- 1870–1873 – St Andrew's Church built to the design of George Gilbert Scott.

- 1874

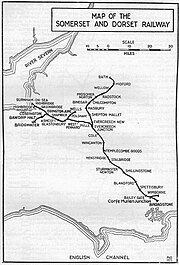

- 20 July: Somerset and Dorset Railway begins operating from Queen Square station.

- Manvers Estate sold.

- 1875

- Bath High School for Girls established by the Girls' Public Day School Company.

- ?: Bath City Police established.

- 1877 – 6 June: Widcombe footbridge collapses, killing eleven, causing it to be rebuilt as a wrought-iron lattice girder.

- 1878

- Bath College opens.[41]

- Corporation acquires Kingston Baths.

- 1880

- 28 February: Bath Golf Club founded

- 24 December: Bath Tramways Company begins operating horsecars.

- Approximate date: Blaine's Folly built.[22]

- 1881 – Population: 52,557.[58]

- 1882 – Holburne Museum fine art collection bequeathed to the city.

- 1883 – Queen's Bath largely demolished revealing a Roman circular bath.

- 1886 – First telephone exchange.

- 1887 – Botanical Gardens opened in Royal Victoria Park.

- 1888 – Bath Photographic Society formed.[59]

- 1889

- 1 April: Bath becomes a county borough under terms of the Local Government Act 1888.

- 21 June: William Friese-Greene, working in Bath since c. 1875, patents a "chronophotographic" camera, an early form of movie camera.[52]

- New douche and massage baths incorporating parts of the Queen's Bath and of the 1786 New Private Baths and including an arch over York Street completed to the design of C. E. Davis.

- Landslide destroys nine houses in Camden Crescent.[60]

- Twerton Co-operative Society, a consumers' co-operative, opens its first shop.[61]

- Bath Association Football Club formed.

- 1890 – Electricity generating station begins operation.[15]

- 1891 – Bath Fire Brigade and Ambulance Service established.

- 1892 – Technical training begins, origin of City of Bath Technical School and Bath College of Domestic Science.

- 1893 – Holburne Museum opens in Charlotte Street.

- 1894 – Major floods.

- 1896 – April: Bath Municipal Technical College and Bath City Secondary School established in a new north extension of the Guildhall.

- 1897

- 18 October: Victoria Art Gallery foundation stone laid to commemorate the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria.[19]

- Henrietta Gardens laid out to commemorate the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria.

- Roman Baths and associated Concert Room designed by J. M. Brydon are opened to the public.[6]

1900s

- 1900

- Silcox Son & Wicks, furnishers, established.

- May: Victoria Art Gallery and Reference Library opens.[12][46]

- New (redbrick) houses for the working classes erected in Dolemeads.[7]

- 1901

- Empire Hotel in business (designed by C. E. Davis).[62]

- Population: 49,839.[10]

- 1902 – 25 July: Horse tram system closes for electrification, being temporarily replaced by horsebuses.

- 1904 – 2 January: Bath Electric Tramways Company begins operating.

- 1905 – 12 December: Midland Bridge, a replacement lattice-girder bridge over the Avon, is opened.

- 1907 – Bath School of Pharmacy established.

- 1909

- c. February: Old Bath Preservation Society, predecessor of Bath Preservation Trust, set up.[7]

- 19–24 July: Historical Pageant staged in Royal Victoria Park.[63]

- St Winifred's Quarry built as a house on Combe Down to the design of Charles Voysey.[6]

- 1910 – Jubilee Hall Cinema operating in Assembly Rooms.

- 1911 – 9 November: Twerton and parts of Charlcombe and Weston are incorporated within the city boundary under terms of the Local Government Act 1888.

- 1915

- T. R. Hayes, furnishers, established.

- December: Robert Atkinson (architect) is commissioned to produce a post-war plan for the city.

- 1916

- Bath War Hospital set up at Combe Park.

- Holburne Museum moves to the former Sydney Hotel.

- 1920 – Bath Tramways Motor Company set up to operate motor buses.

- 1923

- Roman hot plunge baths excavated.

- Kingston Baths demolished.

- 1925

- Bath Corporation Act includes conservation powers.

- Lansdown Water Tower built.

- 1927

- 16 May: New Post Office and Telephone Exchange opens in Northgate Street.

- 3 November: City war memorial dedicated.

- 1929

- 20 June: Cleveland Bridge, having been acquired in 1925 by Bath Corporation and rebuilt, is freed of toll.[19]

- July: Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady & St Alphege completed in Oldfield Park to the design of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott.

- 1931 – October: Assembly Rooms purchased by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings with funds provided by Ernest Cook and transferred to the National Trust for restoration and preservation.

- 1932

- Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution moves to premises in Queen Square.

- 11 December: Royal United Hospital opens on the Combe Park site[64] and its former premises are taken over by Bath Technical College.

- 1934 – Bath Preservation Trust founded.

- 1936–1941 – Haile Selassie, deposed Emperor of Ethiopia, spends most of his exile in Bath.

- 1936 – North Parade Bridge rebuilt in stone-faced reinforced concrete.

- 1937

- Bath Corporation Act includes additional conservation powers.

- A school crossing patrol ("lollipop lady") is appointed, one of the earliest in the UK.

- 1938

- 15 October: Assembly Rooms reopened after restoration.

- Kilowatt House on Claverton Down, a unique example of modernist architecture in the city, is completed to the design of Mollie Taylor as a residence for electrical engineer Anthony Greenhill.[6]

- 1939

- 6 May: The Bristol Tramways and Carriage Company, operator of the Bath tramways, converts the last remaining routes to motor bus operation.

- 3 September: On the outbreak of World War II, departments of the Admiralty begin evacuation to Bath.

- 1942 – 25–27 April: Bath Blitz: Three German aerial bombing raids as part of the "Baedeker Blitz" kill 417; among the buildings destroyed or badly damaged are the newly restored Assembly Rooms, St Andrew's church and All Saints Chapel.[65]

- 1944 – March–November: John Betjeman is assigned to a wartime job working on publicity for the Admiralty at the requisitioned Empire Hotel.[66]

- 1945 – Town planner Patrick Abercrombie produces A Plan for Bath for post-war reconstruction.[67]

- 1946 – October: City of Bath Bach Choir founded.

- 1948

- Bath Assembly (music festival) begins.

- Queen Square is given to the citizens of Bath in memory of those killed in the Blitz.

- 1951

- George Perry-Smith opens the innovative Hole in the Wall restaurant.

- July–August: John Straffen strangles two young girls.

- 1955

- Bath Terraces Scheme introduced to conserve the city's historic architecture.[7]

- Covered reservoir opens on Bathampton Down.

- 1958 – Bus station opened in Manvers Street.

- 1960 – December: Major floods.

- 1961 – Bath Crematorium opens.

- 1963

- 23 May: Assembly Rooms reopen after post-war reconstruction incorporating the Museum of Costume.

- 10 June: The Beatles play the Pavilion.

- 1965–Easter 1983 – Excavations of Roman Baths under the direction of Barry Cunliffe, including areas beneath the Grand Pump Room and in the sacred spring.

- 1965 – Town planner Colin Buchanan publishes Bath: a planning and transport study.[68]

- 1966

- 7 March: Bath Green Park railway station and Somerset and Dorset Railway close with effect from this date.

- November: University of Bath chartered, work having started on its Claverton Down site in 1964.

- Churchill Bridge replaces Old Bridge over the Avon.[15]

- Electricity generating station ceases operation.[15]

- 1969–1972 – Original Southgate Shopping Centre built to the design of Owen Luder.

- 1969 – J. B. Bowler, engineer and carbonated drink manufacturer, ceases business.

- 1970

- 16 May: Reopening of Widcombe bottom lock as part of the restoration of the Kennet and Avon Canal.[48]

- June: Bath Festival of Blues and Progressive Music held.

- 20 June: No. 1 Royal Crescent opened to the public as an historic house museum by Bath Preservation Trust after a 2-year restoration.

- 23–29 September: Adam Fergusson's essay criticising inappropriate development, "The Sack of Bath", is published in The Times newspaper by the editor William Rees-Mogg;[7] it is subsequently expanded into a book with photographs by Snowdon and verses by John Betjeman.[69]

- 1971

- 1973 – 30 March: Beaufort Hotel (later Hilton Bath City Hotel) opens in Walcot Street.

- 1974

- 1 April: Bath becomes part of Avon non-metropolitan county under terms of the Local Government Act 1972.

- 9 December: Irish Republican Army bomb exploded in The Corridor.[71]

- 1975

- Bath College of Higher Education established.

- Hermann Miller furniture factory built by Farrell/Grimshaw Partnership.[6]

- 1978 – Spa baths closed due to contamination.[7]

- 1979

- 27 April: Bath Postal Museum opens in Great Pulteney Street.

- Roper Rhodes bathroom accessories business launched.[72]

- 1981 – Bath Fringe Festival and Bath Half Marathon begin.

- 1986

- 26 July: Major fire at The Colonnades, Bath Street.

- Bristol and Bath Railway Path laid out.

- 1987

- 22 May: GWR FM Bath launches as an independent local radio station.

- December: City of Bath inscribed as a World Heritage Site.[7]

- 1989 – 11 January: Closure of Stothert & Pitt is announced.

- 1991

- 21 April: Population: 78,689.[70]

- Summer: Major fire at Prior Park.

- 1993

- April: Museum of East Asian Art opens.

- May: Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution relaunched at its Queen Square premises; new public library opened in the Podium.

- 1995 – Bath Literature Festival begins.

- 1996 – 1 April: City becomes part of the Bath and North East Somerset non-metropolitan district. Charter Trustees of the City of Bath established.

- 1997 – Ustinov Studio (theatre) built.

- 1999 – 15 November: Bath FM launches as an independent local radio station, broadcasting until 24 March 2010.

2000s

- 2000 – New Wessex Water headquarters on Claverton Down built to the design of Bennetts Associates.[6]

- 2001 – April: city population recorded by the census is 83,992.[73]

- 2002 – Bath Times newspaper begins publication as a free weekly; it ceases publication by 2007.[25]

- 2005

- August: Bath Spa University gains full university status.

- October: The Egg opens.

- 2006 – 7 August: Thermae Bath Spa facility opens.

- 2007

- September: Bath Festival of Children's Literature begins.[74]

- October: Bath Chronicle changes from daily to weekly publication.

- 2008 – Beau Street Hoard found.

- 2009 – Bath bus station and SouthGate shopping centre open.

- 2011

- April: city population recorded by the census is 88,859.[75]

- October: Occupy Bath begins.

- Construction of Bath Western Riverside residential development on former Stothert & Pitt crane factory site begins.

- 2015

- 9 February: A child and three adults are killed and four others seriously injured when a poorly maintained tipper truck runs away down Lansdown Lane into Weston.[76]

- April: City of Bath College renamed Bath College.

- 2021 – March: Clean Air Zone introduced in central Bath.[77]

Births

- c.953 – Ælfheah of Canterbury, archbishop (d. 1012)

- c.1080 – Adelard of Bath, natural philosopher (d. c.1152)

- 1704 – John Wood, the elder, architect (d. 1754)

- 1707 – Benjamin Robins, military engineer (d. 1751)

- 1728 – 25 February: John Wood, the younger, architect (d. 1782)

- 1732 – David Hartley, the younger, statesman and inventor (d. 1813)

- c.1738 – John Palmer, architect (d. 1817)

- 1742 – John Palmer, postal innovator and theatre owner (d. 1818)

- 1744 – 31 May: Richard Lovell Edgeworth, politician, writer and inventor (d. 1817)

- 1751 – Honora Sneyd, educationalist (d. 1780)

- 1754 – September: Elizabeth Ann Linley, soprano (d. 1792)

- 1771 – Frances Brett Hodgkinson, actress in the United States (d. 1803)

- 1773 – 14 January: William Amherst, 1st Earl Amherst, diplomat and Governor-General of India (d. 1857)

- 1780

- 3 June: William Hone, libertarian writer, satirist and bookseller (d. 1842)

- Approximate date: Daniel Terry, actor and playwright (d. 1829)

- 1790 – 19 December: William Parry, Arctic explorer (d. 1855)

- 1794

- 9 September: William Lonsdale, geologist (d. 1871)

- James Dredge, the elder, civil engineer and brewer (d. 1863)

- 1796 – John Pinch, the younger, architect (d. 1849)

- 1807 – Robert Montgomery, poet (d. 1855)

- 1808 – 15 July: Henry Cole, civil servant and inventor (d. 1882)

- 1810 – 2 April: Edward Vansittart Neale, Christian socialist (d. 1892)

- 1816 – 17 March: Abraham Marchant, Mormon leader (d. 1881)

- 1820 – 22 June: Charles Lowder, Anglo-Catholic priest (d. 1880)

- 1835 – 2 April: William Eden Nesfield, domestic revival architect (d. 1888)

- 1840 – 29 July: James Dredge, the younger, civil engineering journalist (d. 1906)

- 1846 – 26 October: C. P. Scott, newspaper editor (d. 1932)

- 1872 – Edith Garrud, née Williams, pioneer martial artist and suffragist (died 1971)

- 1881 – 7 July: Sidney Horstmann, engineer and businessman (d. 1962)

- 1888 – 15 June: Martin D'Arcy, Catholic intellectual (d. 1976)

- 1896 – 7 January: Arnold Ridley, playwright and actor (d. 1984)

- 1898 – 17 June: Harry Patch, supercentenarian and last surviving combat soldier of World War I (d. 2009)

- 1901 – 29 September: Caryll Houselander, Catholic lay mystic (d. 1954)

- 1903 – 17 October: G. E. Trevelyan, novelist (d. 1941)

- 1935 – 24 March: Mary Berry, food writer and presenter

- 1943 – 3 April: Jonathan Lynn, stage and screen director, producer, writer and actor

- 1945 – 17 December: Jacqueline Wilson, née Aitken, children's fiction writer

- 1947 – 4 October: Ann Widdecombe, politician

- 1964 – 24 February: Bill Bailey, comedian and musician

- 1973

- 11 April: Kris Marshall, actor

- 14 May: Indira Varma, actress

- 1974 – 18 January: Princess Claire of Belgium, née Coombs, princess consort

See also

- History of Bath, Somerset

- Timeline of Somerset history

- Timelines of other cities in South West England: Bristol, Exeter, Plymouth

References

- ^ Aston, Mick. "The Bath Region, from Late Prehistory to the Middle Ages" (PDF). Bath Spa University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Geoffrey of Monmouth (1136). Historia Regum Britanniae.

- ^ a b "Saxon Bath". The Mayor of Bath. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b Letters, Samantha (2005), "Somerset", Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516, Institute of Historical Research, Centre for Metropolitan History

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. "Vikings and Anglo-Saxons". British History Timeline. BBC. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Forsyth, Michael (2003). Bath. Pevsner Architectural Guides. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10177-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Spence, Cathryn (2012). Water, History & Style – Bath: World Heritage Site. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-8814-1.

- ^ "Bath Abbey". Sacred Destinations. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tymms, Samuel (1832). "Somersetshire". Western Circuit. The Family Topographer: Being a Compendious Account of the ... Counties of England. Vol. 2. London: J. B. Nichols and Son. OCLC 2127940.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 511–512.

- ^ a b "Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases". Bath Heritage. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Bath". Great Britain (7th ed.). Leipzig: Karl Baedeker. 1910. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010546516.

- ^ a b c Wood, John (1765). Description of Bath (2nd ed.). London: W. Bathoe.

- ^ Townsend, George Henry (1867). "Bath". A Manual of Dates (2nd ed.). London: Frederick Warne & Co.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Buchanan, R. A. (1969). The Industrial Archaeology of Bath. Bath University Press. ISBN 0-900843-04-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Peach, R. E. M. (1893). Street-Lore of Bath. London: Simpkin, Marshall.

- ^ a b Maxted, Ian (2006). British Book Trades: Topographical Listings. Somerset. Exeter Working Papers in British Book Trade History. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Kaufman, Paul (1967). "The Community Library: A Chapter in English Social History". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 57 (7): 1–67. doi:10.2307/1006043. JSTOR 1006043.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Commemorative inscription.

- ^ Haddon, John (1982). Portrait of Bath. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7091-9883-3.

- ^ Mortimer, Roger; Onslow, Richard; Willett, Peter (1978). Biographical Encyclopaedia of British Racing. London: Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 0-354-08536-0.

- ^ a b c d Headley, Gwyn; Meulenkamp, Wim (1999). Follies, grottoes & garden buildings. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-85410-625-4.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Masonic Hall formerly Theatre (443204)". Images of England. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012.

- ^ Historic England (15 October 2010). "1–30 The Circus (1394142)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Bath (England) Newspapers". Main Catalogue. British Library. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ a b Toone, William (1835). Chronological Historian ... of Great Britain (2nd ed.). London: J. Dowding.

- ^ a b Page, William, ed. (1906), "Romano-British Somerset: Part 2, Bath", History of the County of Somerset, Victoria County History, vol. 1, University of London, Institute of Historical Research

- ^ a b Green, Mowbray Aston (1904). Eighteenth Century Architecture of Bath. Bath: G. Gregory. OCLC 1718577. OL 6953596M.

- ^ "History". Bath: Theatre Royal. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Rules and orders of the Society Instituted at Bath, for the Encouragement of Agriculture, Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. 1777. OCLC 85861288.

- ^ "About The Museum". Museum of Bath at Work. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Torrens, Hugh (1990), "The Four Bath Philosophical Societies, 1779–1959", Proceedings of the 12th Congress of the British Society for the History of Medicine, Bath

- ^ Thicknesse, Phillip (1780). The Valetudinarians Bath guide, or, The means of obtaining long life and health. Dodsley, Brown and Wood.

- ^ Although initially recording it as a comet. Herschel, W.; Watson, Dr. (1781). "Account of a Comet, By Mr. Herschel, F.R.S.; Communicated by Dr. Watson, Jun. of Bath, F.R.S". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 71. London: 492–501. Bibcode:1781RSPT...71..492H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1781.0056. S2CID 186208953.

- ^ Historic England (15 October 2010). "The Cross Bath (1394182)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ Historic England. "Numbers 1 to 12 (442847)". Images of England. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

- ^ Historic England (15 October 2010). "South Colonnade at Grand Pump Room (1395196)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Historic England (15 October 2010). "North Colonnade at Grand Pump Room (1395195)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ "Key objects of the collection". Bath: Roman Baths. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Historic England (15 October 2010). "1–8 Bath Street (1394178)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Handy Guide to Bath. Bath: Jolly & Son. 1900. OCLC 12987834. OL 17860578M.

- ^ Historic England (15 October 2010). "Grand Pump Room (1394019)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Wright, G. N. (1864). The Historic Guide to Bath. Bath: R. E. Peach, printer. OL 25319615M.

- ^ a b Winchester, Simon (2001). The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-14-028039-1.

- ^ The Trial of Jane Leigh Perrot. 1800.

- ^ a b c Clegg, James, ed. (1906). International Directory of Booksellers and Bibliophile's Manual. J. Clarke.

- ^ Roth, Cecil (2007). "Bath". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 210.

- ^ a b Clew, Kenneth R. (1985). The Kennet & Avon Canal: an illustrated history (3rd ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8656-5.

- ^ Allsop, Niall (1987). The Kennet & Avon Canal. Bath: Millstream Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-948975-15-8.

- ^ a b c Annals of Bath, from the year 1800 to the passing of the new municipal act. Bath: Printed by Mary Meyler and Son. 1838. OCLC 5258530. OL 23277637M.

- ^ Historic England. "Cleveland Baths (Grade II*) (1396146)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Wallis, Peter, ed. (2008). Innovation and discovery: Bath and the rise of science. Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution; William Herschel Society. ISBN 978-0-948975-82-0.

- ^ "History". Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Historic England. "Cleveland Bridge (442453)". Images of England. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Royal Victoria Park, Bath, Bath, England". Parks & Gardens UK. Parks & Gardens Data Services. 27 July 2007. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Major, S. D. (1879). Notabilia of Bath. Bath: E.R. Blackett.

- ^ "Destruction of Bath Theatre". Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette. 24 April 1862. Retrieved 18 October 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Bath". Handbook for Travellers in Wiltshire, Dorsetshire, and Somersetshire (4th ed.). London: John Murray. 1882. hdl:2027/uc1.l0098676091.

- ^ "Photographic Societies of the British Isles and Colonies". International Annual of Anthony's Photographic Bulletin. New York: E. & H. T. Anthony & Company. 1891.

- ^ Hobbs, P.R.N; Jenkins, g.O. "Appendix 1 Major recorded landslides in the Bath area In: Bath's 'foundered strata' - a re-interpretation Physical Hazards Programme Research Report OR/08/052" (PDF). British Geological Survey. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Pearce, David (2015). "The Co-operative Movement in Bath". Proceedings of the History of Bath Research Group. 3:15–18.

- ^ "Small Talk of the Week". The Sketch. 18 December 1901.

- ^ "Bath Historical Pageant". The Redress of the Past. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "A Potted History of the RUH". Royal United Hospital. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Rothnie, Niall (1983). The Bombing of Bath: the German air raids of 1942. Bath: Ashgrove. ISBN 0-906798-29-9.

- ^ Wilson, A. N. (2007). Betjeman. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-099-49837-7.

- ^ Abercrombie, Patrick; Owens, John; Mealand, H. Anthony (1945). A Plan for Bath. London: Pitman.

- ^ "Brutal Bath" (PDF). Museum of Bath Architecture. 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Fergusson, Adam (1973). The Sack of Bath: a record and an indictment. Salisbury: Compton Russell. ISBN 978-0-85955-002-4.

- ^ a b "Population Statistics". Bath and North East Somerset District Council. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Britten, Elise (15 December 2019). "Looking back on the day an IRA bomb exploded in Bath city centre". SomersetLive. Reach. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Dean, Malcolm (22 July 2017). "Maggie Roper". The Guardian. London. p. 37.

- ^ Bath and North East Somerset Council, Bath and North East Somerset Cultural Strategy 2011-2026 (PDF), p. 40

- ^ "Bath Festival of Children's Literature". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "Bath". BANES 2011 Census Ward Profiles. Retrieved 2 May 2015.(Combined populations of the 16 wards that made-up the unparished area at the time of the 2011 census.)

- ^ "Bath tipper truck crash kills child and three adults". BBC News. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ Barltrop, Paul (25 August 2023). "Bath air quality improves since introduction of clean air zone". BBC News. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

Bibliography

Published in 18th century

- New Bath Guide, or, Useful Pocket-Companion. Bath: Printed by C. Pope, for W. Taylor. c. 1765.

- New Bath Guide, or, Useful Pocket-Companion (New ed.). Bath: Printed by R. Cruttwell for W. Taylor. 1789. hdl:2027/hvd.hxjnl3.

- Christopher Anstey (1766). New Bath Guide: or, Memoirs of the Blunderhead Family (3rd ed.). London: J. Dodsley. OL 16314966M.

- Daniel Defoe; Samuel Richardson (1778). "Bath". A Tour Through the Island of Great Britain (8th ed.). London: J.F. and C. Rivington.

- Philip Thicknesse (1778). New Prose Bath Guide, for the Year 1778. London: Printed for the author. OL 23412268M.

- John Collinson (1791). "Bath". History and Antiquities of the County of Somerset. Vol. 1. Bath: Printed by R. Cruttwell.

- New Bath Directory, for the Year, 1792. Bath: W. Gye. 1792.

- Archibald Robertson (1792). "Modern Bath". Topographical Survey of the Great Road from London to Bath and Bristol. London. OCLC 1633468.

Published in 19th century

1800s-1840s

- Richard Warner (1801). History of Bath. Bath. OCLC 5837002.

- John Claude Nattes (1806). Bath, illustrated by a series of views. London: W. Miller and W. Sheppard. OCLC 32851779.

- Joseph Nightingale (1813). "Bath". Beauties of England and Wales. Vol. 13. London: J. Harris.

- Historic and Local New Bath Guide (4th ed.). Bath: C. Duffield. c. 1815.

- Pierce Egan (1819). Walks Through Bath. Bath: Meyler and Son. OL 7233349M.

- James Dugdale (1819). "Somersetshire: Bath". New British Traveller. Vol. 4. London: J. Robins and Co.

- Gye's Bath Directory. Bath: W. Gye. 1819.

- Robert Watt (1824). "Bath". Bibliotheca Britannica. Vol. 3. Edinburgh: A. Constable. hdl:2027/nyp.33433089888832. OCLC 961753.

- David Brewster, ed. (1830). "Bath". Edinburgh Encyclopædia. Edinburgh: William Blackwood.

- "Bath". Great Western Railway Guide. London: James Wyld. 1839. OCLC 12922212.

- Thomas Bartlett (1841). "Bath". New Tablet of Memory; or, Chronicle of Remarkable Events. London: Thomas Kelly.

- "Bath". Mogg's Great Western Railway and Windsor, Bath, and Bristol Guide. London: Edward Mogg. 1841.

- And Co, Hunt E. (1848). Hunt & Co.'s Directory & Court Guide for the Cities of Bath, Bristol, & Wells.

1850s-1890s

- "Bath". Bradshaw's Descriptive Railway Hand-Book of Great Britain and Ireland. London: W.J. Adams. 1860.

- John Earle (1864). A guide to the knowledge of Bath, ancient and modern. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green.

- "Bath (Somerset)". Where Shall We Go?: A Guide to the Healthiest and Most Beautiful Watering Places in the British Islands (4th ed.). Edinburgh: A. and C. Black. 1866.

- William Henry Overall, ed. (1870). "Bath, Somerset". Dictionary of Chronology. London: William Tegg. OCLC 2613202.

- Smith, George; Thackeray, William Makepeace (July 1873). "Some Literary Ramblings about Bath: III". Cornhill Magazine. Vol. 28.

- James Tunstall (1876). Rambles about Bath and its neighbourhood (6th ed.). London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co. OCLC 12987741. OL 6919886M.

- John Parker Anderson (1881). "Somersetshire: Bath". Book of British Topography: a Classified Catalogue of the Topographical Works in the Library of the British Museum Relating to Great Britain and Ireland. London: W. Satchell.

- R. E. M. Peach (1883–1884). Historic houses in Bath, and their associations. Vol. 2. London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co. OCLC 5463468. OL 7096295M. Archived.

- Concise Guide to Bath. Bath: R.B. Cater. 1885.

- R. E. M. Peach (1888). Bath, Old and New. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Company.

- British Association for the Advancement of Science (1888). J. W. Morris (ed.). Handbook to Bath. Bath: I. Pitman and Sons. OL 19530108M.

- J. G. Douglas Kerr (1898). Popular Guide to the Use of the Bath Waters (12th ed.). Bath Herald. OL 14035086M.

- Bijou Guide to Bath. Bath: Tylee & Co. 1890. OCLC 12987828. OL 19368029M.

- Charles Gross (1897). "Bath". Bibliography of British Municipal History. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Published in 20th century

- Emanuel Green (1902). Bibliotheca Somersetensis. Vol. 1: Bath Books. Taunton: Barnicott and Pearce. OCLC 7080200.

- G. K. Fortescue, ed. (1902). "Bath". Subject Index of the Modern Works Added to the Library of the British Museum in the Years 1881–1900. London: The Trustees.

- William Tyte (1903). Bath in the Eighteenth Century. Bath: Chronicle Office.

- Robert Donald, ed. (1908). "Bath". Municipal Year Book of the United Kingdom for 1908. London: Edward Lloyd. hdl:2027/nyp.33433081995593.

- Bryan Little (1947). The Building of Bath 47-1947: an architectural and social study. London: Collins.

- Walter Ison (1948). The Georgian Buildings of Bath from 1700 to 1830. London: Faber.

- Benjamin Boyce (1967). The benevolent man: a life of Ralph Allen of Bath. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- "Bath in the Eighteenth Century". Apollo. London. November 1973.

- Peter Coard (1973). Vanishing Bath: buildings threatened and destroyed (3rd ed.). Bath: Kingsmead Press. ISBN 0-901571-67-9.

- Adam Fergusson (1973). The Sack of Bath: a record and an indictment. Salisbury: Compton Russell. ISBN 978-0-85955-002-4.

- Adam Fergusson; Tim Mowl (1989). The Sack of Bath and after. Salisbury: Compton Russell. ISBN 0-85955-161-X.

- Charles Robertson (1975). Bath: an architectural guide. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-10750-8.

- Larry R. Ford (1978). "Continuity and Change in Historic Cities: Bath, Chester, and Norwich". Geographical Review. 68 (3): 253–273. Bibcode:1978GeoRv..68..253F. doi:10.2307/215046. JSTOR 215046.

- Bryan Little (1980). Bath Portrait: the story of Bath, its life and its buildings (4th ed.). Bristol: Burleigh Press. ISBN 0-902780-06-9.

- R. S. Neale (1981). Bath 1680-1850: a social history. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-0639-4.

- Christopher Pound (1981). Genius of Bath: the city and its landscape. Bath: Millstream. ISBN 978-0-948975-01-1.

- Barry Cunliffe; Peter Davenport, eds. (1985). The Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath. Monograph 7. Vol. 1: The site. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. ISBN 0-947816-07-0.

- Barry Cunliffe (1986). The City of Bath. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-297-4.

- Tim Mowl; Brian Earnshaw (1988). John Wood: architect of obsession. Bath: Millstream Books. ISBN 978-0-948975-13-4.

- Peter Davenport, ed. (1989). Archaeology in Bath 1976–1985. Monograph 28. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. ISBN 0-947816-28-3.

- G. A. Kellaway, ed. (1991). Hot Springs of Bath. Bath City Council. ISBN 978-0-901303-25-7.

- Peter Davenport (1999). Archaeology in Bath: excavations 1984–1989. BAR British series 284. Oxford: Archaeopress. ISBN 1-84171-007-5.

- Peter Borsay (2000). Image of Georgian Bath, 1700–2000. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820265-2.

- Barry Cunliffe (2000). Roman Bath Discovered (3rd ed.). Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1902-1.

Published in 21st century

- Peter Davenport (2002). Medieval Bath uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1965-X.

- Michael Forsyth (2003). Bath. Pevsner Architectural Guides. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10177-5.

- John Wroughton (2004). Stuart Bath: Life in the forgotten city, 1603–1714. Bath: Lansdown Press. ISBN 0-9520249-5-0.

- Peter Borsay (2006). "Myth, Memory, and Place: Monmouth and Bath 1750–1900". Journal of Social History. 39 (3): 867–889. doi:10.1353/jsh.2006.0001. JSTOR 3790298. S2CID 144152506.

- John Wroughton (2006). Tudor Bath: Life and strife in the little city, 1485–1603. Bath: Lansdown Press. ISBN 0-9520249-6-9.

- Peter Wallis, ed. (2008). Innovation and discovery: Bath and the rise of science. Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution; William Herschel Society. ISBN 978-0-948975-82-0.

- Cathryn Spence (2010). Bath – City on Show. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5674-4.

- Dan Brown & Cathryn Spence (2012). Bath in the Blitz: Then & Now in colour. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6639-2.

- Roger Rolls (2012). Douched and Doctored: thermal springs, spa doctors and rheumatic diseases. London Publishing Partnership. ISBN 978-1-907994-09-8.

- Cathryn Spence (2012). Water, History & Style – Bath: World Heritage Site. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-8814-1.

- Mike Jenner (2013). The Classical Buildings of Bath. Bristol: Redcliffe. ISBN 978-1-908326-03-4.

External links

- "Somerset", Historical Directories, UK: University of Leicester. Includes Bath directories, various dates.

- "Libraries and Archives: Local studies". Bath & North East Somerset Council.

- List of Mayors of Bath, 1230-

Wansdyke

Wansdyke (from Woden's Dyke) is a series of early medieval defensive linear earthworks in the West Country of England, consisting of a ditch and a running embankment from the ditch spoil, with the ditching facing north.

There are two main parts: an eastern dyke which runs between Savernake Forest, West Woods and Morgan's Hill in Wiltshire, and a western dyke which runs from Monkton Combe to the ancient hill fort of Maes Knoll in historic Somerset. Between these two dykes there is a middle section formed by the remains of the London-to-Bath Roman road. There is also some evidence in charters that it extended west from Maes Knoll to the coast of the Severn Estuary but this is uncertain. It may possibly define a post-Roman boundary.

Usage

Wansdyke consists of two sections, 14 and 19 kilometres (8.7 and 11.8 mi) long with some gaps in between. East Wansdyke is an impressive linear earthwork, consisting of a ditch and bank running approximately east–west, between Savernake Forest and Morgan's Hill. West Wansdyke is also a linear earthwork, running from Monkton Combe south of Bath to Maes Knoll south of Bristol, but less substantial than its eastern counterpart. The middle section, 22 kilometres (14 miles) long, is sometimes referred to as 'Mid Wansdyke', but is formed by the remains of the London to Bath Roman road. It used to be thought that these sections were all part of one continuous undertaking, especially during the Middle Ages when the pagan name Wansdyke was applied to all three parts. However, this is not now considered to be certain.

Defence of an unrecorded border

Among the largest defensive earthworks in the United Kingdom, Wansdyke may be compared to both Offa's Dyke (later, and forming a Mercian border with Wales) and Hadrian's Wall (earlier, and forming a border between Britannia and Caledonia). Nennius, an 8th-century Welsh monk who had access to older chronicles since lost, describes these defences and their purpose, and links them to the legends of King Arthur.[1]

Nomenclature and dating

The earthwork is named after their god Woden (Odin), possibly indicating that the incoming Anglo-Saxons had no information about the origins of a structure that was there when they arrived, and which was of no significance to locals at that time.[2] Its name occurs in charters of the 9th and 10th century AD. Its relationship to the expansion of the West Saxons was considered in 1964 by J.N.L. Myres, who maintained that Wansdyke was constructed by some sub-Roman authority.[3] Fowler speculates that it was a fortification intended for use against invading Saxons in the 490s, and abandoned when the news of British victory at Mons Badonicus made it redundant.[4] The name 'Woden's Dyke' eventually became Wansdyke.

East Wansdyke

East Wansdyke in Wiltshire, on the south of the Marlborough Downs, has been less disturbed by later agriculture and building, and is more clearly traceable on the ground than the western part. In places the bank is up to 4 m (13 ft) high and the ditch as much as 2.5 m (8.2 ft) deep. Since at least the tenth century, there have been gaps, "gates", in the work. The ditch is on the north side, so Wansdyke may have been intended by the Romano-Britons as a defence against West Saxons encroaching from the upper Thames Valley westward into what is now the West Country. Fowler suggests that its plan is consistent with those of Roman border fortifications such as Hadrian's Wall: not just a military defence but intended to control locals and travellers along the Wessex Ridgeway.[5] He suggests further that the works were never finished, abandoned in the face of a political change which removed their rationale.[4]

Lieut.-General Augustus Pitt Rivers carried out excavations at the Wansdyke in Wiltshire in the late 19th century, considering it the remains of a great war in which the south-west was being defended.[6] In 1958, Fox and Fox attributed its construction to the pagan Saxons, probably in the late sixth century.[7]

West Wansdyke

Although the antiquarians like John Collinson[8] considered West Wansdyke to stretch from Bathampton Down south east of Bath, to the west of Maes Knoll,[9] a review in 1960 considered that there was no evidence of its existence to the west of Maes Knoll.[7] Keith Gardner refuted this with newly discovered documentary evidence.[10] In 2007 a series of sections were dug across the earthwork which showed that it had existed where there are no longer visible surface remains.[11] It was shown that the earthwork had a consistent design, with stone or timber revetment. There was little dating evidence but it was consistent with either a late Roman or post-Roman date. A paper in "The Last of the Britons" conference in 2007 suggests that the West Wansdyke continues from Maes Knoll to the hill forts above the Avon Gorge and controls the crossings of the river at Saltford and Bristol as well as at Bath.[12]

As there is little archaeological evidence to date the whole section, it may have marked a division between British Celtic kingdoms or have been a boundary with the Saxons. The evidence for its western extension is earthworks along the north side of Dundry Hill, its mention in a charter and a road name.[13]

The area became the border between the Romano-British Celts and the West Saxons following the Battle of Deorham in 577 AD.[14] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Saxon Cenwalh achieved a breakthrough against the Britons, with victories at Bradford on Avon (in the Avon Gap in the Wansdyke) in 652 AD,[15] and further south at the Battle of Peonnum (at Penselwood) in 658 AD,[16] followed by an advance west through the Polden Hills to the River Parrett.[17] It is however significant to note that the names of the early Wessex kings appear to have a Brythonic (British) rather than Germanic (Saxon) etymology.[18]

A 1,330-yard (1,220 m) section of Wansdyke in Odd Down, which has been designated as an Ancient monument,[19] appears on the Heritage at Risk Register as being in unsatisfactory condition and vulnerable due to gardening.[20]

Modern use of name

The Western Wansdyke gave its name to the former Wansdyke district of the county of Avon, and also to the Wansdyke constituency.

Route and points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maes Knoll hillfort | 51°23′28″N 2°34′34″W / 51.391°N 2.576°W | ST599659 | Maes Knoll |

| Stantonbury Camp | 51°22′12″N 2°28′16″W / 51.370°N 2.471°W | ST672636 | Stantonbury Camp |

| Joining the River Avon | 51°21′22″N 2°19′37″W / 51.356°N 2.327°W | ST773620 | Monkton Combe |

| River Avon to Lacock | 51°24′43″N 2°07′05″W / 51.412°N 2.118°W | ST918681 | Lacock |

| Morgan's Hill | 51°24′07″N 1°57′32″W / 51.402°N 1.959°W | SU029670 | Morgan's Hill |

| Shepherds' Shore | 51°23′38″N 1°55′59″W / 51.394°N 1.933°W | SU047661 | |

| Milk Hill | 51°22′26″N 1°51′11″W / 51.374°N 1.853°W | SU102639 | |

| Shaw House | 51°23′13″N 1°48′40″W / 51.387°N 1.811°W | SU131654 | |

| Savernake Forest | 51°22′59″N 1°40′48″W / 51.383°N 1.68°W | SU221649 | Savernake Forest |

See also

References

- ^ Gardner, Keith S. "The Wansdyke Diktat? – A Discussion Paper". Wansdyke Project 21. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Fowler 2001, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Myres, The English Settlements (1986:156); H. Trevor-Roper, "Wansdyke and the origins of Wessex" in Essays in History

- ^ a b Fowler 2001, p. 197.

- ^ Fowler 2001, p. 193.

- ^ Pitt-Rivers, "Excavations in Bokerly and Wansdyke', 1892

- ^ a b Cyril and Aileen Fox, "Wansdyke reconsidered", Archaeological Journal (1958)

- ^ Collinson, The History and Antiquities of the County of Somerset, 1791

- ^ For example see Major, A "The course of Wansdyke through Somerset", Somerset Archaeology and Natural History Society Proceedings Vol 70, 22–37 (1924)

- ^ Keith Gardner, ""The Wansdyke Diktat? Bristol and Avon Archaeology (1998).

- ^ Jonathan Erskine, "The West Wansdyke: an appraisal of the dating, dimensions and construction techniques in the light of excavated evidence", Archaeological Journal 164.1, June 2007:80–108). https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2007.11020707 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00665983.2007.11020707

- ^ Keith Gardner, "The Land of Cyngar the Priest, The Last of the Britons 400–700", published 2009

- ^ "Maes Knoll". Wansdyke Project. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 501–97 AD.

- ^ The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 645–56 AD

- ^ The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 658–75 AD

- ^ The Victoria History of the County of Somerset, Vol 1 (1906)

- ^ Hills, C., (2003) Origins of the English, Duckworth. p. 105: "Records of the West Saxon dynasties survive in versions which have been subject to later manipulation, which may make it all the more significant that some of the founding 'Saxon' fathers have British names: Cerdic, Ceawlin, Cenwalh."

- ^ Historic England. "Wansdyke: section 1,230 yd (1,120 m) eastwards from Burnt House Inn (1007003)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Wansdyke: section 1,230 yards (1,120 metres) eastwards from Burnt House Inn, Southstoke — Bath and North East Somerset (UA)". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Fowler, Peter (2001). "Wansdyke in the Woods: An unfinished Roman military earthwork for a non-event". In Ellis, Peter (ed.). Roman Wiltshire and After: Papers in Honour of Ken Annable. Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. ISBN 978-0-947723-08-8. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

External links

- Wansdyke Project 21 – A project to preserve Wansdyke (the earthwork), last updated 2008

- Wansdyke – Devizes Heritage website, archived in 2010

Combe Down

Prior to Now on Combe Down link: Combe Down development timeline

| Combe Down | |

|---|---|

Holy Trinity Church | |

Location within Somerset | |

| Population | 5,419 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | ST763625 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BATH |

| Postcode district | BA2 |

| Dialling code | 01225 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Combe Down is a village on the outskirts of Bath, England, in the Bath and North East Somerset unitary authority area, within the ceremonial county of Somerset.

Combe Down village consists predominantly of 18th- and 19th-century Bath stone-built villas, terraces and workers' cottages; the post World War II Foxhill estate of former and present council housing; a range of Georgian, Victorian and 20th-century properties along both sides of North Road and Bradford Road; and the 21st-century Mulberry Park development on the site of former Ministry of Defence offices.

Location

Combe Down sits on a ridge above Bath, approximately 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) to the south of the city centre. The village is adjoined to the north by large areas of natural woodland (Fairy Wood, Long Wood, Klondyke Copse and Rainbow Wood) with public footpaths offering views overlooking the city. Parts of these woods are owned and managed by Bath & Northeast Somerset Council, but the majority are owned and managed by the National Trust; the Bath Skyline trail runs north of the woods.[2] To the south of the village are views of the Midford Valley.

Etymology

"Combe" or "coombe" is a word meaning a steep-sided valley derived from Old English "cumb" and possibly from the same Brythonic source as the Welsh cwm. "Down" comes from the Old English "dūn" or "dūne", shortened from adūne ‘downward’, from the phrase of dūne ‘off the hill’.[3]

Governance

Formerly part of the parish of Monkton Combe, Combe Down was incorporated into the city of Bath in the 1950s.[4]

There have been a number of boundary changes and local government changes affecting Combe Down.

- Before 1854: part of the ecclesiastical parish of Monkton Combe in the diocese of Bath and Wells and the civil hundred of Bath Forum in Somerset

- From 1854: part of the ecclesiastical parish of Combe Down in the diocese of Bath and Wells[5] and the civil hundred of Bath Forum in Somerset

- Following the Public Health Act 1875: part of the civil hundred of Bath Forum in Somerset and Bath Rural Sanitary District

- Following the Local Government Act 1894: part of the civil parish of Monkton Combe in Bath Rural District Council in Somerset

- Following the Local Government Act 1933: part of the civil parish of Monkton Combe in Bathavon Rural District Council in Somerset

- Following the Local Government Commission for England (1958–1967): from 1967 part of the county borough of Bath

- Following the Local Government Act 1972 from 1974: part of the district of Bath in the county of Avon

- Following the Avon (Structural Change) Order 1995: from 1996 part of the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset.

Amenities

Combe Down has many local amenities including schools, churches, shops, local societies and pubs. It has two allotment sites: 64 plots on a privately owned site at Church Road, established in 1895, and 10 plots at Foxhill owned by the parish council.

The local state primary school is Combe Down CEVC (Church of England Voluntary Controlled) Primary School, housed partly in a log cabin imported from Finland.[6] The nearest state secondary school (with sixth form) is Ralph Allen School. The independent Monkton Combe School is in the nearby village of Monkton Combe while its prep school, pre-prep and nursery are all in Combe Down village. Prior Park College, an independent Catholic secondary school, is adjacent to the village.

The centre of the village has a range of shops and small businesses. The post office closed in 2006 despite public opposition and the nearest post office branch is now inside a grocery store in a row of shops on the Bradford Road.

There is an Anglican church (Holy Trinity[7]) and a non-conformist chapel (Union Chapel[8]). A Roman Catholic church (Saint Peter and Saint Paul) is on the edge of the village, adjacent to the Foxhill estate.

The village pubs are the King William IV,[9] the Hadley Arms[10] and the Forester & Flower (formerly The Foresters). The King William has not reopened since the pandemic of 2020 and the Forester & Flower opens only for one evening a week, so as at December 2023 the Hadley Arms is the only fully operational village pub.

Combe Down has two flourishing rugby union clubs and a cricket club, a children's nursery, a doctors' surgery and a dentist as well as an active Cub and Scout Group (10th Bath) with its own Scouts' Hut. There are several societies, including an active local history group (the Combe Down Heritage Society), a branch of the Women's Institute and two art groups.

There is a private hospital, Bath Clinic (owned by Circle Health Group) on Claverton Down Road, based at Longwood House, the former home of the Mallet family of Mallet Antiques. Margaret Mary Mallett (1882–1959), who lived at Longwood House, and her daughters Margaret Elizabeth Mallett (1905–1991) and Barbara Penelope Mallett Lock (1896–1978) donated 347 acres (140 ha) of land on Combe Down and Claverton Down including Rainbow Wood farm, Klondyke Copse, Fairy Wood and Bushey Norwood to the National Trust.[11] Opposite the hospital is a 4-star hotel and health club, Combe Grove Manor, with 69 acres (28 ha) of gardens and woodland.[12]

A public open space (Firs Field) incorporates the village war memorial and a play area with children's play equipment. Three parcels of land make up the Firs Field open space, two of which are under the control of the local Council. The deeds state that the Firs Field is intended for the recreation of the residents of Combe Down in perpetuity.[13] Firs Field was restored to meadowland status following the successful completion of the stone mine stabilisation works in 2010. A residents' group (The Friends of Firs Field) exists to ensure the appropriate representation of local residents' interests with regard to the management of the field. In 2015 Firs Field was granted "commemorative" status and designated an official Fields in Trust "Centenary Field".[14]

In July 2014[15] the Ralph Allen CornerStone was opened. It is run by a charity, the Combe Down Stone Legacy Trust, as a sustainable building and educational centre. The Combe Down Heritage Society has museum-standard secure archiving space in the basement where it catalogues and stores unique local heritage material, and which can be accessed by researchers.[16]

There are daily bus services to the village from Bath city centre. The privately owned Bath 'circular tour' bus passes the outskirts of the village and down Ralph Allen Drive on its route to the city centre. The Bath Circular bus (service number 20A) passes through Combe Down and caters for students travelling to the University of Bath and Bath Spa University.

History

It is believed that a Roman villa was situated on the southern slopes of the village somewhere below Belmont Road,[17] the site of which was discovered in the 1850s.[18] An inscription on a stone recovered from the area reads "PRO SALVTE IMP CES M AVR ANTONINI PII FELICIS INVICTI AVG NAEVIVS AVG LIB ADIVT PROC PRINCIPIA RVINA OPRESS A SOLO RESTITVIT". This can be translated as: "For the health of Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Invictus Augustus, Naevius the imperial freedman, helped to restore from its foundations the procurator's headquarters which had broken down in ruins." It is thought to date from AD 212–222.[19] Many finds from the site were taken to the Somerset County Museum at Taunton.

John Leland, the 16th century antiquarian and traveller, noted some stone mining activity in Combe Down as he passed by.

By 1700, small open stone quarries were operating on Combe Down. Most of the land and the quarries were purchased by Ralph Allen in 1726 but there was as yet little habitation.[20]

In 1791 John Collinson describes Combe Down as still undeveloped:

"On the summit of Combedown a mile northward from the church [mc], among many immense quarries of fine free stone, are large groves of firs, planted by the late Ralph Allen, esq; for the laudable purpose of ornamenting this (at that time rough and barren) hill. Among these groves is a neat range of buildings belonging to this parish. It consists of eleven houses [De Montalt Place], built of wrought stone, raised on the spot ; each of which has a small garden in front. These were originally built for the workmen employed in the quarries, but are now chiefly let to invalids from Bath who retire hither for the sake of a very fine air-, (probably rendered more salubrious by the Plantation of firs) from which many have received essential benefit. The surrounding beautiful and extensive prospects ; the wild, but pleasing irregularities of the surface and scenery, diversified with immense quarries, fine open cultivated fields, and extensive plantations of firs...".[21]

From their 1924 history of Combe Down, D. Lee Pitcairn and Rev. Alfred Richardson state that:

"The houses in Isabella Place were built about 1800, and in 1805 when the De Montalt Mills were founded cottages were erected in Quarry Bottom and Davidge's Bottom to take the place of wooden booths which labourers and workmen had hitherto occupied for the day and in which they had sometimes slept during the week. From this time onwards the place began to develop little by little... In 1829 when the Combe Down quarries were disposed of by Mrs. Cruickshank, building further increased...".[22]

The population increased from 1,600 in 1841 to 2,372 in 1901[23] and was 5,419 in 2011.[24]

Stone mines and quarries

Combe Down village sits above an area of redundant 18th and 19th century stone quarries, many of which were owned and developed by Ralph Allen in the 1720s. These quarries were fully infilled and stabilised during a central government-funded project which took place between 2005 and 2010.[25] Over 40 quarry sites have been identified on Combe Down.[26] Only one working quarry (Upper Lawn Quarry) remains on the edge of the village, located off Shaft Road. This supplies high quality Bath stone to the city and across the UK.[27]

John Leland, the 16th century antiquarian and traveller, wrote in the 1500s that he approached Bath from Midford "...And about a Mile farther I can to a Village and passd over a Ston Bridge where ranne a litle broke there & they caullid Midford-Water..2 good Miles al by Mountayne and Quarre and litle wood in syte..."[28] which could be a reference to quarrying around Horsecombe Vale, between Midford and Combe Down.