About Frank

I was born on 23 July 1926 at the Priory at Rainbow Wood.

My father worked as a gardener for a Major Lock and I believe my mother must have worked in the house as I have an old picture of my mother and some of us children with Major Lock’s daughter, Alison.

My eldest brother, Edward, was born at 6 Greendown Cottages, this was the home of my father’s eldest sister, Kate Kellaway.

Another sister was Mrs Rhymes who owned the paper shop in The Avenue.

Another of my father’s brothers was my Uncle Bert, he worked in the shop too.

My father’s youngest brother Charles, worked with his wife (apart from a short time in the RAF during WWII) all his life at Monkton Combe school.

My grand parents lived in what we called Quarry Bottom, I have a picture of her standing in the doorway of what I believe was No 1, now Quarry Vale I believe.

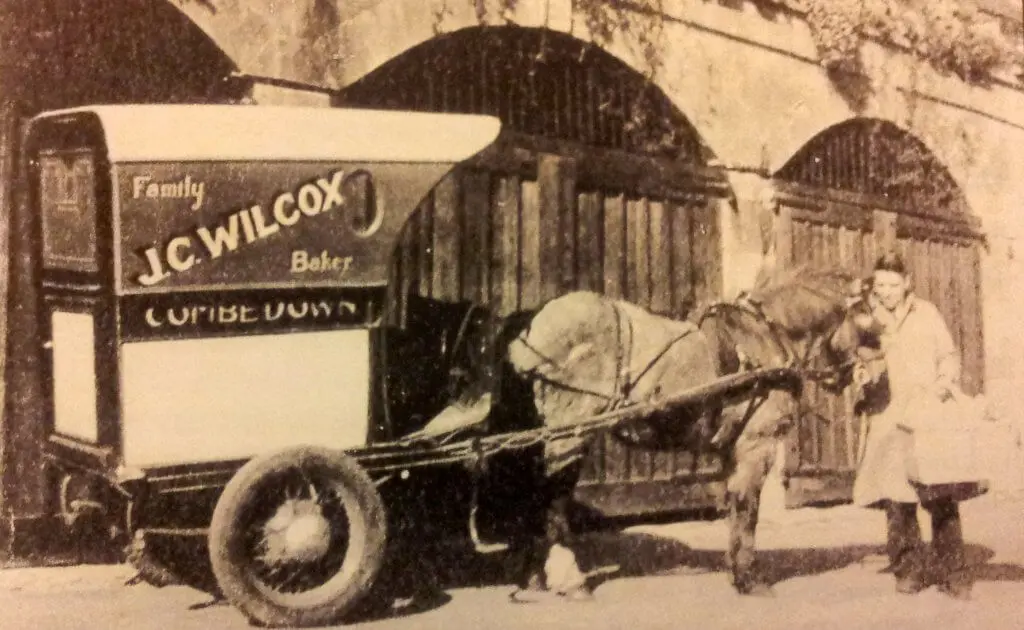

My cousin married Colin Wilcox, the baker in Combe Road.

In my work life I joined Sparrows International Crane Hire and became Managing Director of Sparrows Heavy Crawler Cranes Ltd.

I have a personal website about Sparrows.

Memories of Combe Down

© Frank Sumsion 2017

1930 – 1944

Recently, whilst lying in bed after awaking around 6.45 am, for some unknown reason my mind wandered back to Combe Down (the ‘Down’) and Bath during the time of my childhood and youth.

My first vivid memory as a four or five-year-old child was moving home with my dad, mum, two brothers and sister into an almost derelict cottage in Byfield Place, off Summer Lane, Combe Down.

I clearly remember walking into a very dark room with one gas light in a corner, a stone sink and an iron fireplace with a hob and small oven.

There were two bedrooms upstairs, in one of these was a small hole in the wall that opened into the vacant cottage next door, this cottage was occupied soon afterwards by a family called West.

My dad and Mr West repaired the hole in the wall.

I do not know how we slept upstairs, however, I remember the loo . . . it was in a very small rear garden, approached by a few steps. It was stone-built, about a yard square with a door, and newspaper as a substitute for a toilet roll. There was a bucket, under a wooden plank with a hole in the middle, to this day I do not know where the contents were emptied.

There was a water tap outside the front gate that we shared with the neighbours.

I realised later that we were amongst the poorer families on the ‘Down’.

My dad’s family were very close and two of my aunts were especially kind to us and made sure that we never went without.#

School

My brother George, sister Betty and myself attended the infants’ school in Summer Lane, just a few hundred yards from our home, almost directly behind the church. It was situated on the corner of Summer Lane and Belmont Road. It had an area of about a quarter-of-an-acre of grass, where we played on drier sunny days.

The school grounds were entered by walking across a small grass play area and up a few steps, the classroom was on the left and a small playground extended to the right. Further to the right-hand side was a row of about six to eight toilets (bucket-type again).

I can still recall my first teacher’s name, Miss Brewster.

We used to take a small lunch to school always a sandwich, very often just jam, but sometimes my mother made us a banana sandwich and by lunchtime the banana was almost black but they tasted wonderful, I still make jokes about them today.

Another memory that has lived with me: when playing in Summer Lane on a wet day with my brother George, we were sailing match boxes in the gutter. Mine floated into a drain, George somehow managed to lift the cover slightly open. I put my hand inside but he could not hold the cover and it dropped, as I pulled my hand away it caught my fingers, almost severing the top of the third finger of my left hand. A passer-by noticed the incident and rushed me to the surgery of Dr Morris in The Avenue (I believe the surgery is still there). Dr Morris managed to sew the parts together. The scar and split nail remain, as a reminder. The district nurse called at our cottage to dress the wound every day or so and my mother told me that I used to run and hide as soon as I saw her coming along the lane on her bicycle.

. . . so much for the infant times.

The Village

My memories of Combe Down are still quite clear in my mind, it was all so different then. As children, we wandered everywhere and people seemed to notice you and talk to you more.

Tyning Road was prominent in that many of our class and playmates came from there, the Whittaker’s, Prescott’s and Clothiers come to mind. There were also many pupils brought from outside Combe Down, such as the villages of Hinton Charterhouse and Combe Hay. Fales coaches provided the transport.

The Down as I knew it then, still had many open areas, mostly allotments.

Directly opposite Wilcox, the baker in Combe Road, was a large area of allotments (now Westerleigh Road and housing). At the entrance to the allotments was a large stack, faggots of wood (bundles of wood), that

Mr Wilcox used to heat his bread ovens. All his bread in those days was cooked in his wood-burning ovens.

Walking across the allotments to the far right-hand corner, at the bottom of Rock Lane, was a stone works where you could walk underground into the Combe Down stone mines.

There was another entrance to the stone mines at a quarry behind Combe Down rugby club. This quarry became a landfill site during my childhood days.

Just along from our cottage in Byfield Place was a flight of steps. At the top of the steps, to the right, was a butcher’s shop and next to that was ‘The Jupiter’, one of seven public houses that were on the Down at that time. Across the road from the butcher’s shop was a small builders’ yard and on the corner of Summer Lane and Church Road was Appleby’s the greengrocers.

Continuing along Church Road towards the church (Holy Trinity), on the right-hand side, was a small shop and then a dressmaker.

Another 50 yards or so brought you to Mrs Colmer’s sweet shop, a favourite of ours. Mrs Colmer ran the shop, and Mr Colmer, the local shoe repairer, worked in the cellar below. We wore boots most of the time, the soles covered in studs to make them last, my dad repaired them.

I believe there were two other shops before you arrived at more allotments, my uncle Bert used one of these. Beyond the allotments and continuing along the road there was an entrance to a walkway (drung) to Belmont Road, and after the entrance was Holy Trinity church, where we were all christened. Beyond that again the vicarage and Combe Down senior school, now an apartment block.

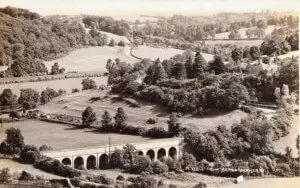

On the corner of Church Road and Belmont Road is another drung, leading to Summer Lane. At the end of the drung, on the opposite side of the road, are Bluebell Steps. These steps drop down to the ‘stream field’ as we knew it. Combe Down Waterworks are at the bottom beside the former railway viaduct at Tucking Mill.

At the bottom of the field to the right, almost under the railway viaduct, was the Combe Down Waterworks pumping station which pumped water to the elevated water tank, opposite the Foresters’ Arms (now the Forester & Flower). It also pumped water to a reservoir at Hampton Down, close to the university, and in the opposite direction across Midford Brook via an underground pipe to a water tank that existed in the Crown car park at Hinton Charterhouse. On peaceful nights the sound of the two large gas-fired engines inside the pumping station could be heard clearly on the Down.

The Avenue on Combe Down holds many of my favourite memories . . .

Entering from Church Road: on the right was the bank, it was an imposing building. Next to the bank there was a small lane. The lane ran to the rear of my Aunt Nell’s newsagents (I believe this is now a cycle shop) and the church rooms. My uncle also had a garage in the lane.

Beyond the lane was a row of three cottages, which included the newsagents, all owned by Aunt Nell (Mrs Rhymes). My brothers and I became ‘paperboys’ for her. Opposite the newsagents were Cobbs the bakers, a chemist and the Co-op.

Next door to Aunt Nell lived the caretakers of the church rooms.

After the cottages came the church rooms building (I was at a dance here when the Bath blitz began). Continuing further were two small shops, then the exit from the lane previously mentioned, then allotments with a row of garages at the rear of them.

Before Williamstowe was Dr Morris’ surgery. He was very well known and I remember my parents recalling his kindness and caring for his patients.

Williamstowe was an unmade lane leading to the baptist chapel, it was a large tin hut. One of its preachers was Mr Noad, he ran the post office in Combe Road. Most of the other buildings in the lane were cottages.

Mr Davies lived in Williamstowe, he was the dairyman and he delivered milk locally, using a yoke across his shoulders and two large churns.

Further along The Avenue was ‘Ings’ the grocers. Their deliveryman was well known on the Down as he rode a carrier bike (it had a carrying frame in front of the handlebars). Rain or shine he always wore a trilby hat.

Next was Fale and Ralph’s garage, it’s where my uncle purchased his petrol. I remember one brand of petrol they sold, Cleveland, it cost 11½ pennies per gallon (approximately 5p in today’s money!). Fales ran a coach service, the coaches were garaged in Gladstone Road (also unmade), off Tyning Road.

At the end of The Avenue, opposite the Hadley Arms, was a shelter for tram passengers. Also there was a drung, this lead to Church Road and re-entered near the school. Two-thirds along the drung was the school playground. Behind the Hadley was the scout hut and a couple of tennis courts.

The Firs Field, or recreation ground, had a small children’s playground at its entrance with swings and a roundabout that you ran beside and pushed to make it turn before jumping on.

Towards the right-hand side of the Firs Field was a ‘light hole’, approximately 20 feet in diameter, it serviced the underground stone mines, it was surrounded by a dry-stone wall three or four feet high. We were told never to climb over the wall.

The war memorial at the top of the field (backing on to North Road) was always well-maintained and we were always taken there on Remembrance Day when buglers and a band often played.

A large party was held in Firs Field to celebrate King George V’s silver jubilee. Aunt Nell had a stall selling sweets and ice cream.

The Firs Field road was still unmade at this time with lots of large puddles during heavy rain, there was a footpath in front of the houses .

The last house, at the North end of the road, was the hairdressers, Mr Pearce, ‘Shaver’ as he was kindly known. Our haircuts? Short back and sides!

Going back now to my childhood memories: we moved from Byfield Place in late 1931 to Odd Down.

Move to Odd Down

My parents now occupied a brand-new council house. This must have been like a gift from heaven to them . . . from an almost derelict cottage on the Down to a three-bedroomed (one with a fireplace) home.

On the ground floor was a front room with a fireplace and cupboards to one side; a kitchen, with a gas cooker and new glazed sink with draining boards either side and a gas boiler for hot water. There was also a larder and a coal room; a bathroom with a bath, wash-hand basin and a flush toilet. And the icing-on-the-cake was electric lighting. They must have been in a dream world.

Our house number was No18, on Upper Bloomfield Road.

The front of the semi-detached house was approached by a tarmac path to the front door with an unmade garden either side, the path then continued to the rear of the house, with a good-sized rear garden.

The few pieces of furniture my parents owned were brought from the Down on a horse-drawn coal cart. My Uncle Bill borrowed the cart from Mr West who lived at No 1 Greendown Cottages.

Upper Bloomfield Road was not fully made-up when we arrived, it needed the top small hardcore filling and steam-rolling. We would watch the rollers rolling back and forth. This was followed by tarmacing and gravelling. The hot tar was spread from horse-drawn, coal-heated tanks. I remember feeling sorry for the horses, their fetlocks were covered in tar which had blown from the spray guns of the men who were carrying out the work. The men also looked almost black. And then, again, came the steamrollers to finish off the final surface.

A new fish and chip shop opened directly opposite our house. A good-sized piece of fish with chips was 6d (2½p today). Further along to our left was a grocers, ‘Dauntons’, and then a brand-new Co-op.

Our milk was delivered by Mr Griffith, he also carried two large churns supported by a yoke on his shoulders, as Mr Davies previously mentioned at Combe Down. Our bread was delivered by Colin Wilcox, from his bakery at Combe Road, Combe Down, in his horse-drawn van. His delivery round included both Southstoke and Odd Down. It was delicious bread.

Coal was delivered by Mr Banks on his horse and cart. He had a yard in the quarry at the rear of Odd Down Cottages on Upper Wellsway.

We had a bus stop almost on our doorstep. The buses were some of the very first used in Bath and ran to various parts of the city, our service ran to Grand Parade. I have a vague memory that it was the No 11 service.

For about a year we attended St Philip’s School on Odd Down but we were not happy.

On our way to St Philip’s School the area between Odins Road, Wansdyke Road and Bloomfield Road was an old quarry being used as a landfill site. Lorries powered by steam were still widely used and the large ones, from the Bath City Steam Co, were often to be seen tipping all types of loads. Horses with carts were also used, offloading waste. Smaller lorries were beginning to replace horse-drawn transport and the Ford and Chevrolet lorries of about 30 cwt / 2 tons capacity were becoming popular, especially with the Bath coal companies.

Somehow we found ourselves back at Combe Down school. I suspect this was partly arranged by Aunt Nell, as we three boys very soon had paper rounds to carry out in the mornings and evenings. It meant leaving home at 6.30 am and cycling to The Avenue, collecting a small amount of newspapers to deliver before breakfast at the paper shop. I loved the breakfast unless it was porridge. In later years my aunts told me that they made me sit until I finished it, but more often-than-not I won (I didn’t finish it) and it was ‘wash your hands’ and off to school.

Halcyon Days

The passing of time has changed many things over the years, none more so than children being out-of-doors.

As a child in the early 1930s, I cannot remember having any worries about being on my own, anywhere, at any time. Going to and from school, whether on foot, bicycle or public transport there was never a problem.

Of course, our parents worried if we were out later than expected but for most of the time we moved around as we pleased. There were obviously things going on that we knew little about but generally, amongst all the poverty and hard times, people coped well. As far as I am concerned, they were ‘the good old days’.

During weekends and school holidays we’d spend day-after-day wandering around fields and local villages, sometimes going for cycle rides but more often just walking through the fields and woods.

The collecting of birds’ eggs was not illegal and as children we would walk many miles along hedgerows seeking out birds’ nests. My father gave us strict rules, we never removed more than one egg from a nest, and never returned to the same nest. However, in this instance time has changed for the good . . . the Protection of Birds Act 1954 put a stop to this, and rightly so.

I vividly remember vast numbers of the once-common lapwing (the peewit). Before the Second World War lapwings would flock at Foxhill. There were no houses only fields, owned by Springfield Farm. Part of my evening paper round involved delivering to an old farmhouse, at the outset of war it was taken over by the Admiralty. During what must have been early summer, I would spend an hour or more sitting perfectly still in the fields, surrounded by hundreds of these birds. Also there always seemed to be a skylark, high in the sky, singing clearly. I never hear it these days. Lovely memories.

Rabbits were to be seen in abundance in the countryside, accompanied by the odd hare. I remember that we found some young hares (leverets), we took a couple home but Dad made us return them.

Wild flowers were in profusion from springtime and all throughout the summer months. There were primroses, violets, bluebells, cowslips, moon daises, dog roses and occasionally a wild orchid.

We had settled at 18 Upper Bloomfield Road and made a few new friends at Odd Down.

My father soon had the garden in shape. The front garden had flowers and the rear vegetables. Dad also had an allotment to supplement the supply of fresh vegetables. He also built a small chicken house and run at the end of our garden, we had a few fresh eggs. Rabbit was our main meat as they were very plentiful and very cheap.

I must have been seven or eight years old when we first had our trolleys. They were assembled using a plank of wood approximately 4ft in length and about 12ins wide. Two other pieces of wood held the axles, the front axle was fixed with a large bolt in the centre, enabling it to be steered using our feet or a piece of rope. At the rear would be a soapbox (bars of soap, such as carbolic, were delivered in wooden boxes about 2ft long x 18ins wide, about 12ins in depth), perfect for sitting in. Most of the wood came from a landfill tip between Odins Road and Upper Bloomfield, the wheels and axles from discarded perambulators.

There were very few cars and lorries on the road . . . We had an excellent trolley run from Odd Down, starting at the top of Combe Hay Lane. It was a free ride all the way to Combe Hay village. Afterwards we’d pull our trolleys back to the start line to repeat the ride, passing the Wheatsheaf Inn (then owned by a local farmer, one of his sons was in my class at Combe Down School), via the old Fosseway Lane.

My paper round, I believe my age was nine-years-old, started with a 6.30 am cycle ride from Odd Down to Combe Down.

My morning delivery consisted of about a dozen or so newspapers. In Belmont Road, Captain Daubeney’s family lived in a large house, on the corner with Summer Lane, I entered through large wooden double gates; then onto Quarry Vale . . . my grandparents once lived here but it was before my time, we always called it Quarry Bottom. Some of the residents I recall here were Mr Elliot; the Robinsons and Milsoms. Also the Fishlock family lived at one of the better-built cottages on the right of the steps that lead up to Church Road.

My evening round, of about 25/30 papers, started at North Road just beyond the Foresters Arms. The first delivery was at Horsecombe Grove; then Cleevedale Road, Mr Pavey, one of our schoolmasters, lived there; then on to Foxhill, fields at this time (as mentioned previously). There was an old farmhouse at the top of Foxhill, on the right, just before you entered the hill (it was near here that I sat with the lapwings).

My next stop was Horsecombe Brow, Mr Brown, our school headmaster, lived here; then Pioneer Avenue followed by Hawthorn Grove. The entry to the grove was from Entry Hill. There were open quarries either side of the grove and also one at the top of Entry Hill, on the corner, as you entered the hill from Bradford Road, it is now a small playing field. I think the shop on the corner of Hawthorn Grove was Ridgeways. My final delivery was a few yards down Entry Hill, to the last house of a short rank, on the right-hand side, it was up a few steps and I can still remember being tired and ready for home.

Moving on . . . nine or ten years old. Most of my Saturday mornings were spent helping my uncle, Bert Sumsion (he worked alongside my Aunt Nell in the newsagents). He had his own paper round, delivering from Mount Pleasant at Shaft Road to Claverton village in the Limpley Stoke valley. I enjoyed going with him.

Mount Pleasant was a row of old stone miners’ cottages, we would park Uncle Bert’s car and walk along the track in front of them. The track was unmade, full of potholes that filled with water in winter. There were a few outside water taps for the people living in the cottages and I vaguely remember a water trough about half way along the rank of cottages. Water troughs were a common sight, welcomed by the many horses used to pull carts.

We moved on to deliver at Combe Grove House (a majestic house, now a hotel and leisure centre) and then along a rough track that exited almost at the start of Brassknocker Hill. There were a few cottages opposite and in one of them we had tea and a biscuit.

We went up the hill, the next delivery was at the old convalescent home. Uncle Bert made several other deliveries and I usually stayed in the car (a Singer 10).

We also delivered to a gamekeeper’s cottage, it was well back from the road on the right, as we proceeded towards Claverton Down. I always went with my uncle to see the gamekeeper, they would usually talk about rabbit shooting and I believe that sometimes my uncle joined him.

We had no deliveries at Claverton Down.

We would drive along another rough track that came out on the road leading down to the village of Claverton and the Warminster Road, delivering papers on the way to Claverton Manor (now the American Museum). We would continue down the hill to a farm in the valley, on our right, before arriving at the village where we delivered to several cottages. The last delivery was to an elderly lady who again gave us tea or cocoa and biscuits or cake, Uncle Bert was a popular man. It would be nearly lunchtime when we returned to the shop.

My uncle also bred budgerigars, he had 20 or 30, perhaps more, in a large aviary above his garage. I helped with the cleaning.

Also on Saturday mornings my brother, George, delivered prescriptions for the local chemist, Davy, John and Aspell. Their shop was in Combe Road between the Jupiter and King William pubs. When he finished his deliveries he came back to the shop and we were given something to eat.

I previously mentioned our return to Combe Down School. My first teacher was Miss Condy, she taught juniors and came from Claverton. She was kind and caring. I soon moved up the general classes and remember most of the teachers names:

- Mr Brown, the headmaster, taught English;

- Mr Pavey, history and geography;

- Miss Tanner (Hetty), mathematics. The most strict teacher.

- Mr Flaherty, science.

Another teacher taught the girls cookery, on the ground floor of the building.

Boys sometimes had gardening lessons, these took place in a small plot next to the infant school, adjoining gardens at Quarry Vale.

Miss Tanner will be remembered by every pupil in her class. We each had small wooden pencil cases, about 1¼” square and 10 inches long. Miss Tanner had a habit of looking over your shoulder. If you made what to her was a simple mistake, she would rap you over the back of your neck, quite hard, with the pencil case. I was very often the recipient. However, it must have done some good, as I went on to win a scholarship at 11 years of age (I don’t know why they called her Hetty).

At the school we renewed our friendships with the local children, Whittakers, Dowdings, Prescotts and Clothiers come to mind.

Weekends and holidays were nearly all spent with our friends on the Down, at Beech Wood or Rainbow Wood, next to the tram terminal where you could walk through to the monument field and on to Claverton.

In Rainbow Wood there were many undulating tracks, we all rode our bikes as fast as we could, not too many spills but very exciting for us.

My first memory of a picnic was a lovely sunny day at Hampton Down. We passed through Rainbow Wood, across the monument field, along a footpath through fields before crossing the road at Claverton Down and walking on to Hampton Rocks as we called them. There were panoramic views in all directions but as children we were more interested in climbing the rocks and looking inside one or two small caves.

Senior School and the outbreak of the Second World War. New friends and a new set of standards.

The time came for me to sit for the scholarships exams. In those days, the exams took place on a Saturday morning at the Oldfield Boys’ School, at Wells Road, in Bath. I was amongst a small group of boys from Combe Down School bright enough to sit for the scholarships and was one of the fortunate ones to gain a pass.

The scholarship results qualified me for acceptance at either the City of Bath Boys’ School or West Central School. There was only one choice for my parents, West Central, as they could not afford the school uniform and all the other expensive items required to meet the standard at City of Bath.

It was still difficult for them to meet the cost of West Central. However, they managed and at 11 years of age, I proudly started my education at my new school during autumn of 1937. The school’s uniform consisted of a black blazer, grey trousers (my first long pair) and a black cap with a navy-blue band around it. Also required were football boots, plimsolls, a white singlet and shorts for sports and physical training, somehow my parents found the money to pay for them.

West Central School (now a nursing home) was at the bottom of ‘The Hollow’, in Lymore Avenue, Bath, and opposite the world-famous Blackmore and Langdon’s Garden Nurseries, a mass of colour in the summer.

The school had two main streams of education, commercial: specialising mainly in accounting and office work (typing and shorthand); or practical: technical skills such as carpentry and metalwork were the general criteria.

Of course, we still had all the other general subjects of maths, geography, history, and French, etc. Sport was very much to the forefront and we had two half days each week at the sports ground or at one of Bath’s municipal swimming pools.

I spent my first month or two at the school in the commercial stream, however, I did not enjoy it, I moved to the practical stream and was much happier.

The discipline at school was very strict and the standards were high. If a teacher noticed that you were lagging behind in a particular area or subject it was recognised and individual attention given to you.

All the teachers were popular with the pupils, they were:

- Headmaster: Mr Anderson (Andy).

- Deputy head and mathematics teacher: Mr Hayman (Bill) – some of you may know Mr Hayman, he taught maths at Bath Technical College after the war.

- French and geography was Miss Mitchell (Froggie).

- Mr Jones (Chippie): practical (carpentry and metalwork). He was a well-known organist who often played at Bath Abbey. He was also choirmaster at St Paul’s Church and (apparently) very fond of sports mistress Miss Taylor (Knickers).

- I cannot recall the name of the history and sports master. I believe it was Hillier but I do remember that he went into the armed services during the early days of the war and was killed shortly afterwards.

The school was about one mile from home, all downhill, bicycle was my transport. Coming home was hard work, all up hill, and after a while I began walking to and from school.

The pupils came from all districts of Bath and I made a new circle of friends. Lionel Kite, John Townsend, Bill Taylor, John Canterbury (son of the bakers in Chelsea Road), Freddie Firth (who lived at Englishcombe village in a small cottage with his family. I remember going there fairly often as his mother baked lovely cakes), and Ray Harris, are a few that I remember.

Lionel Kite became a good friend and after the Bath Blitz in 1942 at the age of 16 years, we both joined the Bath Civil Defence Service as dispatch riders. I have not met Lionel since but in the mid 1950s I met Ray Harris, who was workshop supervisor at a local Vauxhall car dealership. Years later we met again and he was then a director of the company. Also, in later years, I became involved with Freddie Firth’s brother who ran a service station under the railway arches at Widcombe. Freddie moved to France and I have never seen him since those schooldays.

I did not excel in any particular subject, woodwork, maths and geography were my best grades. My annual examination results placed me in the top six or seven of the class in those particular subjects, which, bearing in mind that there were about 35 pupils in the class, was (in my opinion) not too bad. My results in other subjects were not brilliant.

At the swimming baths I competed well and was always up with the leaders. I still have the certificates for distance swimming. However, I soon realised that this subject would not help me in any career or occupation when schooldays were over.

When the war started in 1939 I remember standing with Mum and Dad (my sister Betty was probably present too) at the front of our house in Bloomfield Road. Our neighbours, the Butler family, were in their front garden talking to my parents. The radios were switched on in both houses and the windows were open, we were waiting for Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister, to make his broadcast declaring war on Germany.

The declaration of war against Germany was made at 11 am on the morning of Sunday the 3rd September 1939. When war was declared, and it came as no surprise, our parents and neighbours (Butlers) were upset and shocked to say the least. No one had the slightest idea that it would be six long years before the war would end.

It was a sad day for us all, and I knew my parents immediately began to worry about Ted and George who were already serving with the Armed Services.

Both my father and Mr Butler had served in the First World War. Dad served with the Somerset Light Infantry in the Middle East and fought in Mesopotamia, Turkey, Iraq, and Palestine, where besides losing many of his comrades, he lost his best friend. I cannot remember him ever talking at any length about his wartime experiences.

Within a few months, emergency schemes of all sorts began to take place, everyone was issued with a gas mask and these had to be carried at all times. The building of street air raid shelters began and Morrison shelters were available for each house.

The Morrison shelters were built of heavy grade steel in the form of a table about 6ft x 4ft in size and normal table height. The family would get beneath them if an air raid seemed imminent. The sides were protected by a strong wire frame to prevent rubble from hitting those inside if a bomb struck the house (in towns and cities that were bombed regularly families often slept in them).

Concrete water tanks were placed at strategic points around the city. They were there to supply water to the Auxiliary Fire Service in case water mains had been damaged during an air raid. Every house was also supplied with a small water pump (stirrup pump), to extinguish any fires caused by incendiary bombs in their own homes.

During this time I was still attending West Central School (my sister, I believe, had just started to attend Oldfield Girls’ School). All schools had to carry out their own air raid precaution (ARP) exercises.

When the air raid warning sounded we had to walk in an orderly manner to nearby houses where we were taken in, six to a house. This was intended to ensure that if bombs fell locally a minimum number of children would be involved in any one incident. We had our own individual gas masks and these we had to carry with us at all times.

If our satchels, containing books and personal items, were beside us in the classroom when the warning sounded, we could also take these. And, if there was time, we were allowed to collect our coats from the locker room. The drill was immediate evacuation of the school in the shortest possible time.

I think children matured very early during the war years.

It was not many days after the war began that news of the air raids on London came through . . . then the epic story of the British Expeditionary Forces being rescued from Dunkirk and the capitulation of France, followed closely by the Battle of Britain and heavy and sustained air raids taking place all over the UK.

We had early personal experience of these air raids when the Germans began their nightly bombing of Bristol and the South Wales ports, Bath was directly below their flight path.

Bristol was only 12 miles away and as children of 13 or 14 years of age we would watch the raids take place from the top of Rush Hill, a few hundred yards from our home. The sound of the high explosive bombs could plainly be heard, and the fires caused by the incendiaries were clearly visible.

We were quickly aware of the effects of food rationing as many familiar foodstuffs began to disappear from the shops, tropical fruits being one of the first things to go, oranges and bananas were almost impossible to obtain from the very early days. Every item of food and drink was rationed.

Having been poor for so long in our early years our parents soon adapted to the times of austerity but Mum was a wonder and we never went without.

With all these things going on around us it was no wonder that children grew up and matured very quickly.

Many changes were taking place in our family life, my father was directed to work at the underground ammunition dump at Monkton Farleigh, near Bath. The ammunition dumps together with underground factories were built in the old stone mines that honeycombed that part of Wiltshire. Dad was now earning a far better wage than he was paid at the flock mill.

The Admiralty had moved from London to Bath and they initially took over local hotels and built new properties at Combe Down (Foxhill), Lansdown and the Warminster Road areas of Bath.

My mother began work as a cleaner at the Admiralty, mornings 7 am until 9 am and returning in the evening to work from 6 pm until 7.30 pm. She also retained small cleaning jobs during the day with local households. I wondered in later years where she found the stamina to keep going, she was always busy and seemed to be dashing everywhere.

In view of Dad’s increase in his income, and Mum working too, the financial situation for my parents was much improved and times became a lot easier.

Starting work

My first job, as a foolish teenager, and a lesson that money is not everything.

1941. I was desperate to earn a wage of my own and, against my parents’ wishes (especially my mother), I left school just after my 15th birthday. The official leaving age at elementary school was then 16 years old. There was a fine of £2 for leaving school early which my parents paid, they insisted that I would have to pay them back as soon as I started employment.

My first job was with a friend of my brother George, together they had attended Combe Down School. George’s pal was now a lorry driver for a coal delivery firm in Bath, Skeates, on the Upper Bristol Road. I became his mate on the lorry. My weekly wage was one pound and five shillings but within a few weeks I was earning (with tips) as much as my father but it was hard work. We operated from the LMS (S&D) sidings in Midland Road, Bath, and delivered coal in and around the local area. The coal sidings were situated on the site now occupied by Sainsbury’s supermarket and the Homebase store, also it was here that I learnt to drive.

I worked at Skeates for a few weeks but another coal merchant, who lived close to my home at Odd Down, asked me to join him, his name was Jim Hunt. Jim was a hard worker and an excellent boss, I was working for him when the Bath Blitz took place. However, I soon became to realize that this was not the work for me.

A memory of the Bath Blitz

On the evening of 25 April, 1942 at the tender age of 16, I attended a dance at the Avenue Hall (Church Rooms) at Combe Down, Bath. My sister and several of my relations were there also. At about 11.30 p.m. the organiser said the dance must end as an air raid was taking place on the city of Bath. We left the dance hall and hurried to the home of our cousin, “Wilcox the Baker,” at Combe Road, Combe Down, where we sheltered in the basement until the end of the first raid, even there, some two miles from the city centre, the noise was terrifying in its intensity.

The raid lasted about 1 hour and we stayed with our cousin for another hour or so before my sister and I decided to walk to our home at 18 Upper Bloomfield Road, Odd Down, as quickly as possible as we knew our parents would be worried.

We were proceeding along Bradford Road between Fox Hill and Entry Hill when the second raid started, from memory I believe it was close to 3.30 a.m. There were no houses at Fox Hill at that time, just fields belonging to Springfield Farm and we had a clear view over the city towards Lansdown. We could clearly see the huge glow and smoke billowing to the sky from the fires already burning from the first raid.

As the raid started the planes came in very low, it seemed almost above our heads and were diving down over the city. In previous months we had watched the raids on Bristol many times from the top of Rush Hill, where we could clearly see the fires and explosions as they were taking place, but this was a new experience for us, very frightening and very close.

We watched, spell bound, for sometime and then as far as I recall we ran all the way home. Our parents were very relieved to see us; they were sheltering in the smallest room in the house which was a coal cellar between the larder and the living room. Being inside the cellar gave us the protection of two walls either side. We had two near misses; one bomb hit Colborne Road close to the Wansdyke Inn about 100 yards away and another hit Ballantyne and Rudds Garage, in Upper Wellsway, again about a 100 yards away. The only damage to our house was a few cracked windows, front door being jammed and the back door being blown open.

Early the following morning I went with my employer (who had a lorry) into Bath, to see if we could help. The damage was horrific, the civil defence and fire brigade were doing everything they could. There were hosepipes everywhere.

My clearest memories are of the devastation at the Bear Flat, Oldfield Park and Green Park, and the ruins of the churches also stand out in my memory.

My wife (a girl of 15 at the time) lived with her family quite close to the Bear Flat in Chaucer Avenue, their house was badly damaged and they were forced to move to High Littleton near Devizes to live with relations until the end of the war.

St James Church was being used as a mortuary, parties of civil defence workers were combing the buildings looking for survivors and we heard of several success stories during the day where people had been pulled from the wreckage of their homes. Sad stories kept emerging of tragedies where whole families had been killed, and the loss of life of the civil defence workers killed by a direct hit on an air raid shelter opposite the Old Scala Cinema in Oldfield Park

We helped a dentist, Mr Butcher, recover some of his equipment from the basement of his property at Green Park where they were also looking for survivors and were then told to clear the area because of the danger of collapsing buildings.

I can remember old tramlines sticking out from the ground close to the Midland Station at Green Park. The trams had been taken out of service a couple of years previously, if I remember correctly.

My memory of things that happened during the rest of the day is vague, but I remember making several trips to the countryside, taking people in my employer’s lorry. Here they found refuge wherever they could in case the bombers returned at night time.

We were without gas and water, I cannot remember if the electricity was affected. I was at home with my family when the bombers returned after midnight on the night of the 26th. If anything the noise seemed louder than ever. Although we had a Morrison shelter in our living room, which served as a table for the duration of the war, my father thought having the two walls either side of us was the safest place in the house. We spent the duration of the raid (about an hour it seemed) in the coal cellar again.

There was a smell of burning. This turned out to be soot that had shaken from the chimney (had we been in the Morrison shelter the soot would have covered us), we were lucky that we only had the clearing of this to tend to in the morning.

The next day we again used the lorry to take people to places such as Dunkerton, Combe Hay and Peasedown. Once there they were taken in by the local people, to shelter and rest during following days. Jim Hunt, my employer, at that time had relatives at Trowbridge and we decided to take their offer of shelter during the night of the 27th.

We slept on the floor of the Liberal Club in Trowbridge that night and returned home the following day as the bombers had not returned.

After all this time what still amazes me is that with all the loss of life and the devastation that surrounded us, how seemingly quickly things returned to normal. Perhaps it’s because of the passing of time and the innocence of youth.

New job

Shortly after the Bath Blitz my Uncle Bert asked me if I would like to join him at Combe Down Waterworks as an apprentice, he thought (rightly) that it would be a far better job for me than being a coalman. I would work with him learning to maintain and repair the company’s water supply services. My coalman days were over, I left Jim during the autumn of 1942.

The waterworks supplied a large area to the south west of Bath. The job was interesting, involving some shift work at the pumping station at Tucking Mill, in the Midford valley.

I enjoyed my time at the water works, especially working with my uncle. There were two large ‘Crossley’ coal/gas-powered engines at the station and they operated around the clock, keeping the reservoirs at Combe Down, Claverton and Hinton Charterhouse full. Two permanent engineers were employed and we were taught basic maintenance procedures for the two engines and were expected to keep the coal/gas production units fired up to capacity at all times.

We acted as and when required as engineer’s assistants. Mr Bishop (Pooch) the brother of the works manager was one of them; the other was Mr Tom Hamblin (Rattler), a well-known character from the village of Monkton Combe less than a mile away.

The works were about a 20-minute cycle ride from my home at Odd Down, perhaps 25 minutes on the way home, as it was mostly up hill.

I have never forgotten ‘Rattler’ he was a wonderful man, a bundle of fun and loved by all the locals. He was a big man, tall and very strong, reputed to be the only person ever to have the strength to throw a stone over the railway viaduct that ran adjacent to the pumping station. Rattler was also well known in his village for his work at Monkton Combe involving local charities.

My stay at the waterworks lasted for about a year, the pay was not very good and I began to get itchy feet. I was now 16 years old, owned a motorcycle, and had joined the Bath Civil Defence Service as a volunteer dispatch rider.

I could also drive an automobile. There was no driving test during the war, you applied for a provisional licence and it was usually granted, your word was taken that you were competent to drive.

Petrol could only be obtained if you had a valid reason to use a vehicle for work or essential use, as I was in the Civil Defence I had access to an allowance. My ARP report point was close to the Cross Keys pub on Midford Road. We had to book in every Sunday morning and occasionally Saturday afternoons for air raid practise training and spent at least one night a week on duty at the post or at the Bath’s ARP headquarters at Apsley House on Newbridge Road, Bath.

I had a succession of different motorbikes, the first was an Ariel Red Hunter, then a Douglas twin-cylinder, followed by an AJS 500cc which I kept until I joined the army. My mother hated all of them and worried every time I rode. Mum also worried when I was driving the lorries . . . but that was Mum.

Like many teenagers I made as much noise as possible when riding the motorbikes and rode as fast as they allowed us. No crash helmets, except when on duty with the ARP.

As so many other teenagers my leisure activities consisted of visits to local dances, big band concerts and other events that were taking place during the Second World War.

Dances were held locally at venues around the city and I enjoyed going to many of them. We usually had an hour or so at a the pub before the dance, this seemed to be the ‘in thing’ with everyone during the war.

On one occasion, after a dance at Combe Down, Betty, my sister, had a ride home on my pillion seat. It was close to midnight and extremely foggy. At a crossroads close to home there was a large shop on a corner (the Glasshouse Café). The fog was dense, I could barely see the road. Before we knew it I had ridden directly into the shop doorway and hit the front door. We both fell off the machine, without any bruises or scrapes. Luckily we were going very slowly. We never checked the door for damage (I checked the bike, of course). We re-mounted and arrived home safely. It was some years later before we told Mum, she would have killed me if she had known that Betty was on the motorbike.

Even though most of us were well under-age we used pubs quite often. Pub landlords seemed to accept the presence of teenagers and under-age customers.

By this time I was able to pay my share of expenses at home. Mum still kept a strict hold on money and I can never remember her ever getting in to debt.

There was a vacancy for a lorry driver at a local mushroom farm. Much to the disappointment of my uncle Bert I applied for the job and, with only the basic skills of driving, I obtained the position.

As a driver at the farm, I was expected to drive any of three different vehicles, a vintage 4-ton Morris Commercial truck that required the use of a starting handle as there was no self-starter; a ½-ton Austin van; and if the van would not start, the owner’s small car. Luckily for me driving seemed to come naturally and I had no problems.

During this time, I became a close friend of John Harding (‘Nobby’, later to become the owner of a fleet of refrigerated lorries) and we spent lots of time together going to the local dances and underage drinking at local pubs.

It was also around this time that Jane, the girl who later became my wife, entered my life. John was with me when I first saw her, it wasn’t love at first sight but I was really impressed. Jane lived with her parents and family in ‘Glen Cott’, a cottage behind the garage that was once the forge/blacksmiths at the lower end of Oolite Road, Odd Down (both now demolished and replaced with a small apartment block).

When I first saw Jane, she was wearing one of her sister’s Land Army emerald green jumpers. She had lovely auburn, shoulder-length hair and looked wonderful. Little did I know then that we would spend over 64 years of happy married life together.

I cannot remember when or how Jane and I became attached, but we went to the cinema together several times and she came to my parents’ house on Bloomfield Road. Mum and Dad thought the world of her.

Jane wasn’t into dancing or drinking, but I was. I often made a date with her and let her down by going off to a dance or the pub with Nobby.

Dad often chastised me for breaking dates. Most evenings he passed her house whilst walking to the Red Lion for his usual drink (it was common for men and women to meet at the pub each evening).

One very special thing I should mention, on one occasion when Jane and I visited the Red Lion. On the steps at the entrance I gave Jane a small sterling silver ring (no value at all) and placed it on her little finger. I had completely forgotten this until some years later, after we had married. Jane mentioned the ring and recalled the spot I had given it to her, she told me that she had treasured it and worn it continuously from that day at the Red Lion. She wore it for over 70 years until she sadly passed away in 2013. Julie, my daughter, wears it now.

Another thing Jane told me was that she had seen me before I knew her. She used to see me leaving home as she caught her bus to work, the bus stop was almost outside our front door. On our first date her elder sister said: ‘You’re not going out with that Sumsion boy, are you? He used to deliver coal’. Luckily for me Jane kept the date.

Returning to my work days. The mushroom farm was situated in Byfield Lane, Combe Down, only a few yards from the old cottage where we lived before our move to Odd Down (it was now almost derelict and used as a store by a local person). The farm was quite large and from memory had about 10/12 employees. The mushrooms were grown in large sheds (approximately 100ft long and 40ft wide), in compost, on long tiers of shelves that stretched the length of the shed. It was quite productive and most of the crop was dispatched to London. I would take a small load of about 50/60 punnets in the van to the GWR station each morning (there were two main stations in Bath at this time). The rest of the day I would be out with the lorry delivering used compost to local gardeners.

On the odd occasion I would go to Usher’s Brewery at Trowbridge, to collect used hops, these would be dried and packed for sale as another form of fertiliser.

The old Morris Commercial truck was a nightmare to drive. I believe it was 1930-vintage and had no front brakes. I quickly learned to use the lowest gears on steep descents and great care was required when negotiating hills in and around Bath. This was good training for me in my early days of driving. The ½-ton van was an Austin of about the same vintage.

The farm was owned by Mr Robinson, he lived at Horsecombe Brow and was a good employer. The foreman I remember well, Jack Townsend, he lived in a cottage close to the Jupiter Inn. I earned a reasonable wage there but within a few months another better-paid job came up . . . so I moved again.

It must have now been the late summer of 1943. I started driving for a small building and decorating business. The yard was at the bottom of Coronation Avenue and the lorry was a 3-ton Bedford tipper and fairly new, I believe it was a 1938 model. The work entailed taking the tradesmen, their ladders, bricks, paint, plaster, etc, to different building sites around Bath and the surrounding area. Lots of repair work was taking place after the Bath Blitz. There was a lot of work clearing bomb sites around the city and during the day the lorry was hired out to the council and I worked for some time helping to clear different bombed sites in Oldfield Park, mainly Moorland Road.

The best of the reusable Bath stone was taken to the council yard on Entry Hill, the rubble taken to old the disused quarry at the top of the hill. The lorry was a hand screw tipper, it was hard but rewarding work. It was whilst I was working here that I decided to join the Army.

At this time if you joined the regular army you had a choice of which section of the service you wished to join, I wanted to be a driver. The officer at the recruiting centre in Queen Square suggested I join the RASC (Royal Army Service Corps). The downside was that I had to sign up for a fixed period, in my case seven years with the colours (in the army) and five years on the reserve. As both of my brothers had joined ‘boys service’ under similar circumstances, this did not seem a problem.

On 17th April, 1944, with my Dad standing beside me, I signed on the dotted line without a thought of what might lie before me.

470 Coy (company) Ambulance Car Sarafand, Palestine. Early 1947 and the partition of Palestine

On my return to Palestine and 258 Coy at Haifa, I found there had been many changes and lots of my friends had been transferred. I was posted to 470 Coy RASC, an Ambulance Car Company, stationed at Sarafand, near Tel Aviv. There were some 40 Ambulances and the company also ran a fleet of Dodge troop-carrying trucks, about 100 vehicles in total.

I was to be transport sergeant/drill instructor with the Coy until we moved to Egypt (on November 29, 1947, the United Nations passed a resolution calling for Palestine to be partitioned between Arabs and Jews, allowing for the formation of the Jewish state of Israel).

There were only two or three other sergeants in the company and, of course, a Sergeant Major (Tommy Bolger), a Liverpudlian who became a good friend of mine. We were all under canvas at the camp and it was a busy life, the ambulances had regular runs between local camps and the military hospital and on several occasions became involved in the aftermath of terrorist activity.

My father had written to me and asked if I could find the grave of his close friend, Sergeant Charlie Edwards, Somerset Light Infantry. Charlie had been killed in Palestine, at the age of 33, during the First World War. Dad had served in the Middle East, then known as Mesopotamia, fighting the Turks, allies of the Germans.

The grave was at the Imperial War Graves Cemetery at Ramleh (now Ramla). I found the cemetery on the Tel Aviv road to Jerusalem and located his grave, plot CC 75. Charlie was killed on the 25 March 1918. The cemetery was maintained to the high standard of the commission’s cemeteries around the world.

Whilst stationed at Sarafand I had many opportunities to travel around Palestine (under strict security), and visited several of the many historical sites, Nazareth, Galilee, Jerusalem, Jaffa and also the Dead Sea.

Many of us swam in the unique seawater of the Dead Sea where it is impossible to sink without special equipment. On leaving the water we were covered in what seemed to be a thin coating of oil, the result of many chemical deposits, showers are provided on the beach to remove them. It was quite an experience.

The terrorist activity continued unabated until the decision to partition Palestine was made by the United Nations to end the British mandate in 1948, the country was divided into separate regions Jewish and Arab (on December 11, 1947, Britain announced the Mandate would end at midnight on May 14, 1948 and its sole task would be to complete withdrawal from Palestine by August 1, 1948).

From memory 470 Coy left Sarafand in February / March 1948, we broke camp after dismantling all the tents and temporary accommodation. Nothing was left standing as we moved out, all temporary buildings, offices, ablution blocks and other temporary facilities were raised to the ground.

My role was to assist in the organising of the company into convoys for the trip across the Sinai Desert, across the Suez Canal, via the El Firdan Bridge, into Egypt and eventually to Quassasin, where the company was to be re-grouped and sent to East Africa.

Again, from memory, we split the company’s vehicles into three groups of 35 / 40 trucks or ambulances, each group with two despatch riders and myself on a Matchless motorcycle (I rode the motorcycle for the entire journey from Sarafand to Quassasin), controlling all three sections. The trip was without incident and I cannot recall a problem during the whole passage, the journey being split over three days.

Eventually the Coy was disbanded at Quassasin and the majority of our personnel were posted to 240 Coy, Mackinnon Road, Kenya. I cannot recall the events leading up to us leaving but I do remember a trip to Cairo whilst we were there. We only stayed at Quassasin for a couple of weeks before sailing from Port Tewfik to Mombassa, on the troopship ‘Georgic.’ I did not enjoy my time in Egypt, and have no wish to return.

Troopship MV Georgic to Kenya

The troopship MV Georgic (previously a liner on the Southampton-New York route) was a complete contrast to the troopship Battle Axe that I first travelled on across the Mediterranean. The Georgic was much larger and quieter and the ship was only partly full. All on board were going to Mombassa to join different companies in and around Kenya and East Africa.

We had all the usual crazy activities involving ‘King Neptune’ ceremonies as we crossed the equator. A water tank was erected on deck and all of us were ducked in seawater and covered in flour, it was a fun day.

Afterwards each of us received a certificate confirming our crossing of the equator.

Kenya was experiencing terrorist activity and once again we were to be among insurgents seeking independence. In this case it was the Mau Mau who were very active during my short stay in East Africa. Ironically, they treated many of their own people badly, especially if the British Army, Government or white farmers employed them. The problem ceased in 1956 when the rebel leader Mau Mau, Dedan Kimathi was captured, signalling their defeat and ending the British military campaign.

On disembarking at Mombassa, we were taken to a transit camp near Nyali Beach, the coastline and beach were beautiful.

I was posted, as transport sergeant / drill instructor, to 242 Coy Tank Transporters. The towing units were American Diamond T and the multi-axle Rogers trailers, normally used for tank transportation, these had been converted to carry pipes for the ill-fated, British-backed, ‘groundnut scheme’ (a failed attempt by the British government to cultivate tracts of Tanganyika, modern-day Tanzania, with peanuts). We carried pipes from Mombassa to the Tsavo River and Mackinnon Road (a town in Kwale County, Kenya), near the small town of Voi where we were based.

We were in a basic tented camp, the offices and mess halls were Nissen huts and in poor condition.

There was no need for me to carry out any of my duties as a drill instructor as there was no parade ground, discipline was very lax but we were well fed and looked after.

Medical conditions were strict. For health reasons we were issued with, and told to drink, at least one bottle of lime juice a day. Even though we had been inoculated against malaria it was essential to take anti-malaria tablets. We always used mosquito nets at night, as the area was close to the Tsavo River and was known to be a breeding ground. The area is now the Tsavo River National Park and famous for its population of giraffes and elephants.

There were only about six or seven members in the sergeants’ mess but we were well catered for and the bar was well used. The only relaxation was the occasional weekend in either Mombassa or Nairobi. I went to Nairobi on one occasion, it was then a city of two parts, black and white, almost to the extent of partition.

The roads consisted of hard-packed red clay and during dry periods our vehicles travelled at least a quarter-mile apart because of huge dust clouds created by those in front.

The road through our camp was the main highway from Mombassa to Nairobi. In heavy rain the road would resemble a river of mud, making it impossible to use the tank transporters. Our all-wheel drive vehicles also had difficulty travelling during these periods. In many areas the railway ran parallel to the road. It was not unusual for our drivers to board a train to return to camp, if they were forced to abandon their vehicles when the roads became impassable.

When driving a Diamond T from Mackinnon Road travel time to Mombassa was 4 – 5 hours, it was a further 6 – 7 hours drive to Nairobi. There was very little civilian traffic and no one travelled after dark.

The area is well known for its wild animal population but I did not encounter any of note. Monkeys though could be a menace, especially in Mombassa where they kept us awake at night as they ran across the tin roofs of our accommodation. What I disliked most though were centipedes, they were mostly harmless but they were anything from six to twelve inches long and I hated them.

On one occasion I was a passenger on a transporter travelling back to Mackinnon Road from Mombassa, we ran into trouble with the Rogers trailer.

The trailers had three sets of eight-wheeled axles and it was impossible to see the trailer when loaded and travelling, all you could see was a cloud of red dust behind. The tractor unit (the lorry towing the trailer) had overheated and we were forced to stop. When the dust had settled we discovered a huge pile of earth had formed between the tractor and the trailer. We could move the earth with the equipment we had and the night duty truck had passed us, from memory we were some ten or twelve miles from camp. Fortunately, we heard a train in the distance, two of the drivers ran off to stop the train and we thumbed a lift to Voi Junction, close to Mackinnon Road.

The following day we returned with a recovery vehicle. After a lot of hard work we removed all the debris to find that each tyre on the front axles had disintegrated. We returned to camp to collect a mobile crane to off-load the pipes and then turned the trailer upside down (this was general practice when changing tyres or axles). It required the use of two more tractor units and their winches to complete the procedure. After a hard day’s work we were ready for bed when we eventually got back to camp.

Our camp was quite close to the village of Voi and we went there on the odd occasion to buy fruit and other goods. Also at the village was a tailor who produced a made-to-measure for me. I shared a tent with our workshop sergeant, Bill Dyson, we became good friends during the few months I was there. Bill came from Halifax, Yorkshire, we kept in touch for a short while after I came home but never met again.

One morning Bill and I awoke to find that all our kit and everything else in the tent had been stolen, the only clothes left were our shirts, slacks and boots that we had kept inside the mosquito nets. I believe it was a weekend and the previous night we had had a heavy session in the sergeants’ mess, neither of us had heard a sound. The only good thing to come out of it was that we were sent to the quartermaster’s depot in Mombassa and fitted out with new uniforms.

We believed it was an inside job, the guards had not seen anyone leaving or entering the camp. There were many locals employed, laundry men, cleaners, waiters, etc, none of whom could be trusted. We also had some local drivers, who were useless and lazy and all of them were accident-prone.

I cannot say that I really enjoyed my eight months or so in East Africa (Mombassa apart), I found it dusty, dirty and unhealthy. I was probably spoilt by the cleaner and healthier conditions I’d encountered in Palestine (excepting the terrorists).

As my service in Kenya was nearing its end, I befriended a transit sergeant who had the job of arranging the transport for personnel to and from the UK. He asked if I would like to fly back to the UK. I was very wary of flying, nearly all the aircraft were old DC-3s, the most used transport aircraft of the war, many had crashed. Ironically, I found out at a later date that the DC-3 was one of the safest aircraft, the reason we heard about their crashes was solely because there were so many of them in service, even today many of them are still flying.

To cut a long story short, the sergeant said I could fly home if I preferred, it would save me six weeks on a troopship.

At this time, there were major issues in Malaya (once again, insurgents looking for independence). The Army was flying troops to the Far East by BOAC (now British Airways), on the return flights out of Malaya the aircraft would divert via India, East Africa or the Middle East for a return load. Nairobi being the airport for the Kenya stop.

I was lucky, there was a space on an Avro York British transport aircraft. The plane carried 44 passengers and was very comfortable. This was the first time I had ever been inside an aircraft and I had never flown. We departed from Nairobi, situated over 5,000 feet above sea level where the air is slightly thinner than normal. Older passenger aircraft required a longer runway for take-off than normal at this height. This was completely foreign to me and I had no concerns . . . until the air hostess said she was very worried that we were so close to the end of the runway before the aircraft was airborne.

We passed above Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro, it was a wonderful sight, their peaks covered in snow, we then set course north to our first stop, Khartoum.

At Khartoum we left the aircraft to have a meal in the airbase before taking off again for the night flight to Castel Benito, an RAF base near Tripoli, Libya.

As we flew out of Khartoum, across country, the route took us over a vast bush fire, we witnessed thousands of wildebeest stampeding to escape the inferno. It was a stunning sight for us but not too good for the wildebeest.

The flight to Tripoli was uneventful and we landed around 7 – 8 am, again we left the aircraft and were fed at the RAF base. No complaints about the food, we were well treated all the way home. I believe the flying time was about 23 hours, the flight speed being about 230 mph. A similar flight today would take a maximum of eight hours.

We landed at Heathrow late afternoon. Heathrow was in its infancy, slowly beginning to develop into a major UK airport. During the war and until late 1945 Heathrow was a RAF base, there were still many of the RAF wartime huts still in use. It was mid-1946 before the first international flights used it as an airport. We disembarked and were sent on our way very quickly. RAF Northolt became the base for military flights once they had left Heathrow.

I arrived home on 20 October and Jane and me were married on the 30 October. After the wedding, we had a couple of weeks together before I re-joined a holding battalion at Colchester.

The end of service

My posting to Farnborough was as a drill instructor, however, when I arrived there was no vacancy.

I worked in the transport office for a few days before being offered a job as assistant to the officers’ mess steward. This was an excellent opportunity to get away from regimental duties, no parades or guard duties and a peaceful life away from the usual harassment of Army life in general.

The mess steward was a sergeant from Scotland who was shortly to be discharged from the Army. It gave me the opportunity to take on his job, subject to the approval of the president of the mess, Major Patterson, who was very easy to get along with.

I had my own room at the mess, situated over the kitchen, shortly after I moved in I realised that my room was part of what had been, in peacetime, the civilian quarters of the mess steward.

I had applied for a married quarter at the camp but there was a long waiting list. I decided to approach the battalion quartermaster, a major living in the mess. I asked if it was possible to reinstate the quarter I was in, and if it was possible, could I have it? It was agreed and within a few weeks Jane arrived, sometime during May or June of 1949. A few weeks later I was promoted to sergeant again and I became the mess steward.

It was almost like being in civilian life, especially now that Jane and I were together at Farnborough. Life was good. We had Army furniture but within a few months we managed to purchase some of our own as Jane had obtained a position at the National Gas Turbine Establishment (NGTE) at Cove, not far from the officers’ mess.

At the mess there were 12 batmen, two cooks and a couple of cleaners, all in their own quarters on the top floor. The colonel’s batman also lived at the mess, he was a well-built lad named Cox (Busty) from Wells, Somerset and he owned a Harley Davidson motorcycle. Another keen motorcyclist was Fernyhough, who originated from the Manchester area.

I had a corporal under me who lived in married quarters in the camp and took over when I was away on other duties or on leave.

Initially we had an Irishman, a Corporal ‘Paddy’ Dorgan, as the mess cook, he had been there a couple of years. When Paddy left he was replaced by a sergeant from York, hence his nickname, ‘Yorkie,’ he was an excellent cook.

There were special nights when the officers held regimental dinners and they were always memorable occasions. The dining room was laid our accordingly with mess silver, candelabras, etc and all was polished and shining for the occasion.

A considerable amount of silver had been accumulated over the years and the best of it was placed along the centre of the dining room table for each function, usually the cups that had been won by the battalion at special events, including cricket, football, horse riding, shooting. It was an impressive display.

The officers would meet for pre-dinner drinks in the lounge. It was my role to open the large double doors of the dining room, and then the doors to the lounge and, after asking the Colonel for his permission, I would announce: ‘Gentlemen, dinner is served’.

Myself and the batmen, who acted as waiters on these occasions, would be in dress uniform. The batmen wore white jackets and I would be wear blue, it was very formal. Dinner normally consisted of five courses and the food was a very high standard. The wine was served by two of the batmen, trained to ensure that no one was left without a full or half-full glass.

There were two bars at the mess, one was for general use during evenings and weekends, when only a few officers were present. The other bar was situated in the lounge and either myself or the corporal or one of the waiters was on duty in each night. The lounge bar was always open at lunchtimes and either I would be on duty or the corporal.

We soon became aware of the favourite drinks of various officers. No cash exchanged hands but all drinks had to be recorded and signed for by the officer and entered in to the mess account, as and when they were served. It was my role to keep accounts and I had to present them daily to the duty officer who would agree and sign them accordingly.

It was also my responsibility to order all the food from the stores and outside suppliers, including all the drinks for the bar. The alcohol was kept in a strong room with all the mess silver.

Most of the officers were very easy to get along with, especially Major Patterson, who was president of the mess and second-in-command of the battalion. Major Patterson was a great character and well-liked by all, he was always life and soul of the party, my wife Jane and I have fond memories of him.

When our son, Mike, was born at Farnham Hospital, just before midnight on the 24 August 1950, Jane’s mother came to stay for a couple of weeks, to help Jane during the first few weeks after his birth. In all honesty, Jane was more than capable of all that was required and soon became an accomplished Mum in a very short time, handling any little problems as they came along with no trouble at all.

My Mum and Dad came to stay for a short visit too, and brother Ted, his wife Dot and family also came for a long weekend. Where they slept and how we managed I do not know, but we had a wonderful time.

While at Elles Barracks we purchased our first transport, a 1934 vintage Morris Minor, an ex post office van. We bought it from a garage at Bexhill-on-Sea and I travelled by train to collect it. The van was very dated and still painted in post office red, with silver-painted spoke wheels. On our first visit to Bath Ted painted it green and black. I fitted it with two double bus seats, it was perfect transport for ourselves, Mike and his pram, and enabled us to travel to Bath for the odd weekend.

With Jane now working at the NGTE we managed to purchase replacements for some of the Army furniture in our apartment, we also lived fairly comfortably as some of our food was subsidised by the officers’ kitchen below.

We had lived in the officers’ mess for almost four years, until the end of May 1952, when my regular service ended and I discharged from the Army, after completing eight years in the service at home and abroad.

During the last few weeks, prior to my discharge, we moved from the officers’ mess into one of the Army quarters at the camp, allowing the couple who were taking over stewardship to move into our apartment. Our new accommodation was in good condition and we lived there until we returned to Bath, to a prefab at Chelwood Drive, Odd Down, Bath, with my parents.

Contents

- 1 About Frank

- 2 Memories of Combe Down

- 3 1930 – 1944

- 4 School

- 5 The Village

- 6 Move to Odd Down

- 7 Halcyon Days

- 8 Senior School and the outbreak of the Second World War. New friends and a new set of standards.

- 9 Starting work

- 10 A memory of the Bath Blitz

- 11 New job

- 12 470 Coy (company) Ambulance Car Sarafand, Palestine. Early 1947 and the partition of Palestine

- 13 Troopship MV Georgic to Kenya

- 14 The end of service