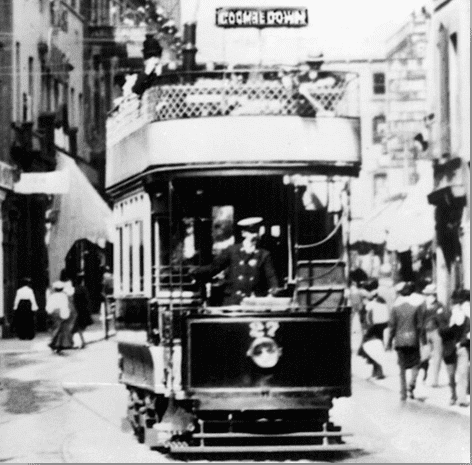

Bath Tramways

Bath had horse drawn trams from 1880. The reduced friction of rail tracks meant that horse drawn trams could carry more people on the flat in more comfort compared to horse drawn omnibuses. Slopes were a different matter.

Another problem was that many horses were needed as regular changes had to be made.

The advent of electricity generation and other advances led to experiments with electric trams.

By 1899 there were proposals to introduce electric trams to Bath.[1]

By 1902 the details had been worked out.[2] The Bath Electric Tramways first service ran on 2nd January 1904 and service ceased on 6th May 1939.[3]

The greater flexibility and lower cost of buses won.

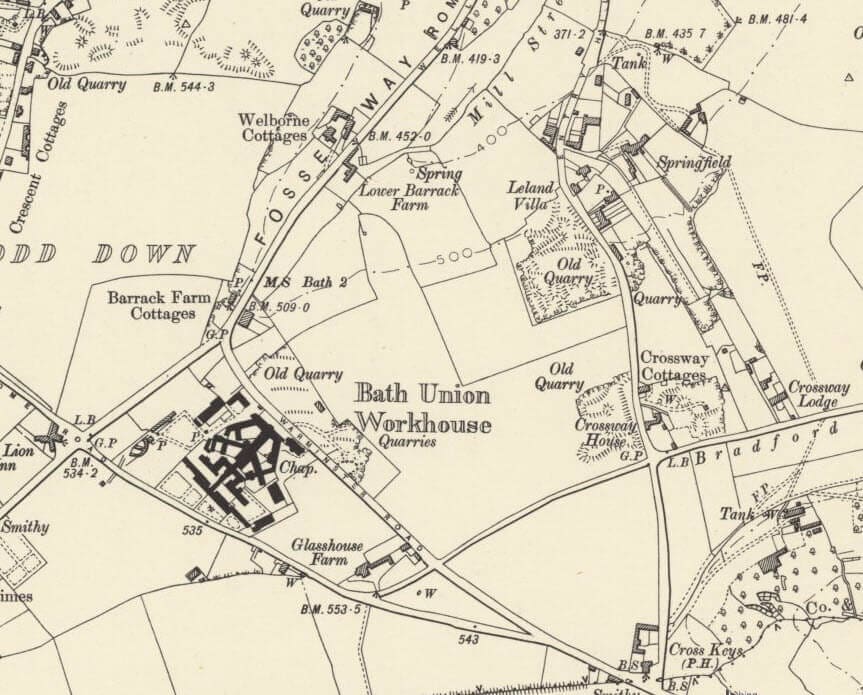

The route to Combe Down came up the Wellsway and then along Midford Road to Glasshouse, then turned East along Bradford Road and North Road to Shaft Road.

Boundaries Fight

1908 saw “the great boundaries fight”.

Bath Corporation wanted to include Bathampton, Charlcombe, Monkton Combe and Twerton as well as parts of Batheaston, Claverton, Swainswick and Weston within the city.

A Mr. E. A. S. Fawcett who was a Local Government Board Inspector came to Bath in December 1908 to start an enquiry.[4]

The boundaries that existed in 1908 had been set in 1835 and Bath was surrounded by Bath Rural District Council which had about 32,000 inhabitants to the city’s 50,000.

The Corporation thought that the boundary was arbitrary and the situation was absurd. They also had to plan for water and sewage and the Bath Corporation Water Act 1903 gave the city new sources of supply including on Combe Down such that the Corporation had made a provisional agreement to take over the Combe Down Water Company. There were also other issues to do with education, lighting and other matters.

The areas outside the city saw things a bit differently. They saw a loss of independence and higher rates as the issues.[5]

Things rumbled on, sometimes getting quite heated, but on 9th November 1911 an enlarged Bath came into existence. It did not encompass all the areas that the Corporation had wanted, but did include Twerton and parts of Weston and Charlcombe. Combe Down eventually became part of the City of Bath in 1967.

Sewerage

The question of mains sewerage had arisen for some years [6] since the 1890s, but Combe Down was felt to be one of the “healthiest districts round about”.[7]

Although Pasteur had shown what was happening with germs, sewage and waste water was felt by many to be something that would self purify once released into the earth or large bodies of water. The role of sewage in contaminating water courses was not fully understood even though the Public Health Act 1875 comprehensively encompassed housing, sewage and drainage, water supply and contagious diseases.

By the 1880s it was becoming well known that contaminated water was likely to spread disease. However, even as late as 1900, a sharp debate on septic tanks and the bacterial purification of sewage took place at the annual meeting of the British Medical Association.[8]

At the time sewage on Combe Down either went into a cesspit or people used the sewage tank which was near the infant school.[9]

However, by 1906 it was acknowledged that something had to be done as more pressure was put on the local council by the Medical Officer of Health and the County Council.[10]

A committee had been set up to look into the question in 1905.[11]

The boundaries fight – in which Bath Corporation had suggested a sewage scheme for Combe Down – and continued pressure from the County Council[12] brought things to a head[13] and in 1910 it had been agreed, even though some people felt the scheme was too expensive,[14] to apply to the Local Government Board for a first loan of £9,000.[15]

It was not to be plain sailing as Monkton Combe School continued to object to the site chosen[16] as did Colonel Skrine.[17]

A month later there was more trouble at Monkton Combe Parish Council as it emerged that the Rural District Council had “brought forward a sewage scheme practically that they might not be absorbed by the City of Bath”.

It was alleged, by Mr. Dudley, who lived at Glenburnie, that:

“the parish council has been put to unnecessary expense and grossly deceived by our representative on the district council.”

The members of the Parish Council agreed and the representative, Mr. W. G. Lane was censured.[18]

There continued to be issues with the site and with people wanting a link up with Bath Corporation sewers. However, eventually it got the go ahead.[19]

The First World War interrupted completion and in 1921 the Bath Trades and Labour Council agreed to approach the City Council and the Rural District Council to get the work restarted.[20]

By 1923 with the laying of further sewers through Foxhill by the city council the sewering of Combe Down reached some level of completion.[21]

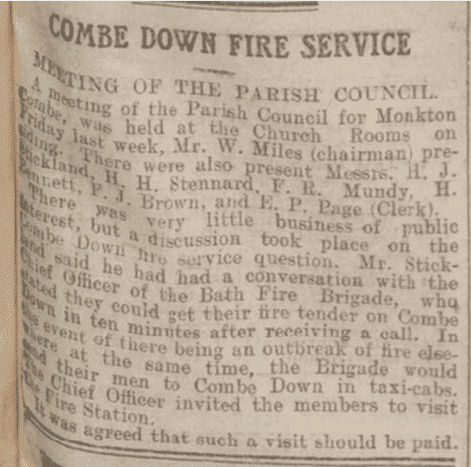

Fire Protection

We take the existence of the fire service pretty much for granted. But, until very recently, that was not so.

Although towns had some fire protection from insurance companies it was disjointed and, frequently ineffective, not just because the equipment to fight fires was ineffective, but also because one insurance company would not fight a fire for a building protected by a rival.

By the 1850s steam powered fire engines allowed larger quantities of water to be pumped, but that assumed the water was available from a hydrant.

Bath had formed a fire brigade in 1891.[22]

In an area such as Combe Down which was up a long and steep hill and quite far from the city centre and where there were no fire hydrants it was another matter. In 1896 there was only one fire hydrant at the top of Entry Hill and a bad fire that killed 2 people focused attention on this.[23]

During the fire someone had had to run to the police box at Bear Flat to report the fire and, when that did not work, run to the fire station to make a report. It then took the brigade 15 minutes to turn out and 20 minutes to get up the hill. The police had also turned out with their fire truck. Hoses had to be run 700’ to reach the fire.[24]

It was not, however until 1912 that 8 hydrants were agreed, though the payment of an 8 guinea p.a. retainer to Bath Corporation for the services of the fire brigade was felt to be ‘a needless expense’.[25]

The question of what else to do was to be referred to a public meeting and some time later a visit to the Fire Station was arranged.

The laying of more mains over subsequent years by the Combe Down Water Company helped to improve the situation but even in 1927 there was concern that there would be insufficient pressure in the mains to cope with fires in all circumstances.[26]

The Second World War led to the formation of the National Fire Service in 1941 and they opened a station on Midford Road just opposite St. Martin’s Hospital, where Cross Manufacturing are now. This was to help with the wartime raids and ceased operation in 1945.

In the 1950s and 1960s it was used by the Auxiliary Fire Service which was disbanded in 1968.[27]

Telephone Service

Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) invented the telephone and made his first one in 1875.

By 1879 two telephone companies were operating in London. In 1880 a court judgement said that, within the meaning of Section 4 of the Telegraph Act 1869, a telephone was a telegraph and that a telephone conversation was a telegram.

Thereafter, independent telephone companies had to obtain 31 year licences to operate from the Postmaster-General. The Post Office took 10% of gross income and had the option to purchase the company at the end of ten, 17 or 24 years. It was Post Office policy to issue licences for the few existing telephone systems, restricting these systems to areas in which they were operating, and to undertake the general development of the telephone itself.

This did not stop entrepreneurs from setting up.

In 1881 the Provincial Telephone Company, the National Telephone Company and the Northern District Telephone Company were all set up.

In 1883 the Long Distance Telephone Company told Bath Corporation they intended to link Bath with London.[28]

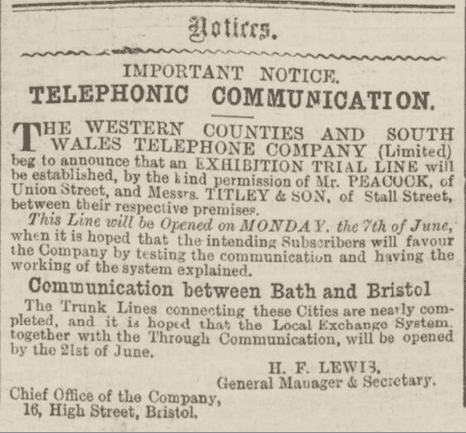

In 1885 the Western Counties and South Wales Telephone Company said they wished to link Bath with Bristol.[29] By the following year they were operating in Bath.

Having taken over the Lancashire and Cheshire Telephone Company in 1889, in 1890 the National Telephone Company absorbed the Northern District Telephone Company and the South of England Telephone Company. Then, in 1892, the Western Counties and South Wales Company, the Sheffield Telephone Exchange and Electric Light Company and in 1893 the Telephone Company of Ireland Limited.

Exactly when the first telephone arrived on Combe Down I have not established. There was a proposal to link the Guildhall and The Bath Statutory Hospital at Brassknocker Hill in 1897[30] and the Rural District Council had a discussion about the number of and payment for telephone poles later that same year.[31]

By 1910 the National Telephone Company had an exchange at 18 Combe Road,[32] directly opposite where a new exchange would be built in the 1930s. The Post Office however had agreed to acquire NTC’s system on the expiry of its licence on 31 December 1911, part of the original licence agreement of 1881. On 31 December 1911 the GPO took over the NTC and its telephone systems.

A new telephone exchange was built on Combe Down between 1933[33] and 1939 even though it was stated in the Bath Chronicle that the exchange would be completed by May 1937.[34] It operated as such until the late 1970s, soon after which it became a branch of the New Christian Church until 2005.[35] In 2014 it became a nursery school.

The other part of telephone service on Combe Down was, of course, telephone kiosks.

In 1913, soon after the GPO took over the National Telephone Company, Monkton Combe parish council noted that there were no public telephone facilities on Combe Down and it was resolved to ask for one.[36] Clearly the war intervened as one was still being requested in 1923.[37]

The GPO said the council would have to guarantee £15 10s p.a. which they were not prepared to do.[38] The request was then refused by the GPO.[39]

In 1929 the council agreed to accept the GPO terms at the time to erect a public telephone kiosk.[40]

By 1933 a second kiosk was erected near the water tank on Bradford Road.[41] Now that mobile phones are so common it does seem rather quaint, but, before mobile phone technology, public phones could, literally, be a life saver.

Bath and West Show

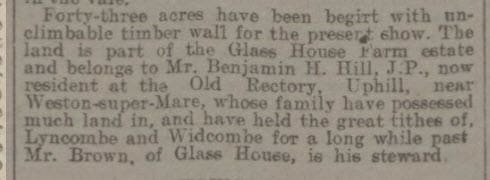

In 1912 the Bath and West Show was held on the Glasshouse Farm estate.

From 1852 until 1965, when the Shepton Mallett showground was purchased by Royal Bath and West of England Society the show was peripatetic and came to Bath for its centenary in 1877 (down by Bear Flat), in 1891, 1900, 1912, 1953 and 1960.

In 1912 43 acres surrounded by a wooden wall, with an entrance of Wellsway were used. The show ran from 30 May until 4 June. 39, 324 people attended and the show took £3,352 in receipts. There was a ‘main road’ to the grandstand which held 2,500 and the show ring and was 550 feet long and 220 feet wide. Behind the grandstand was stabling for 100 horses.

Glasshouse Flying Field

Glasshouse Field is named after ‘Mr.Bennet’s Glass House’ Built in the late 17th century.

The Mr Bennet in question is either Philip Bennet (1637 – 1725) or Philip Bennet (1678 – 1722) who married Jane Chapman (1672 – 1722) and thus inherited Widcombe Manor. R E M Peach confirms in Bath Old and New that Glass House Farm was part of the Widcombe Estate.

Exactly what it produced is unclear bottle making has been mentioned but it could have been ‘flint glass’ which, after George Ravenscroft‘s (1632 – 1683) patent expired in 1696, led to many glasshouses being set up to produce clear lead glassware on an industrial scale and export the results exporting all over Europe.

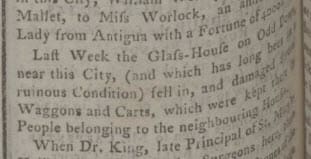

It had already gone out of production by the early 18th century and had been converted to a farm, but a tall glass furnace cone which provided a notable landmark visible for many miles around remained standing for use as a cart-shed and did not disappear until it collapsed in a storm in 1764. The farm was eventually demolished in the 1970s and replaced with a block of flats.

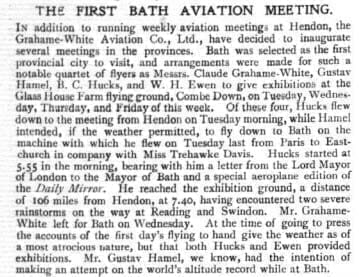

In 1912 Herbert William Matthews, FRIBA (1874-1954), a Bath architect, who had helped to organize the hugely successful Bath pageant of 1909 and a friend, Claude Grahame-White, the first pilot to make a night flight, during the Daily Mail sponsored 1910 London to Manchester air race decided that Bath should be one of the venues for their aviation meetings. The aviation meeting was a huge success.

The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette for Saturday 25th May 1912 states that ‘the several flights made during this week have been witnessed by thousands of spectators both inside and outside the aviation ground’.

It also said:’…In the afternoon Mr Ewen for nearly half an hour circled immediately over the field and the spectators had every opportunity of witnessing the ease with which his dainty-looking machine was manipulated. Cheer a upon cheer rang out when he alighted and the applause was renewed when he brought it to a standstill before the enclosure… Mr. Hucks distributed some of Jolly’s vouchers and as the crowd swarmed the ground the police and officials called in van for them to clear. Mr, Ewen, seeing the danger, brought his machine within thirty of forty feet of the ground. It had the desired effect, for even the stalwart constables took to their heels. Both aviators made safe descents and were awarded with round of applause…’

Of course, the flying field did not last. By the 1930s housing development had taken priority. But, just for a moment…

Herbert Matthews also helped to found Aerofilms Ltd. with Claude Grahame-White (1879–1959).

The Great War

At the beginning of the First World War, Prior Park was taken over by the army.

In October 1914 the 2nd / 4th Somerset Light Infantry commanded by Lieut-Col. H. F. Clutterbuck were located there.[42] It had about 1,000 men and some were billeted in the village.

There were rumours that the men were the victims of ill treatment which led to letters in the Bath Chronicle, including a statement by the men, denying this.[43]

In January 1915 about 350 men of the 5th Somersets and about 475 men of the 4th Dorsets arrived and were billeted in Combe Down and Widcombe as well as other parts of Bath.[44]

Members of the Royal Army Medical Corps were quartered at Combe Grove.[45]

Soon after the Bath Chronicle started running photographic articles under the heading:

The question of ‘curtailment of lighting’ arose in case of German air raids but as the gas company would not ‘take off a penny’ Mr. G. Treasure at the parish council meeting said:

“Then we had better have the benefit of the lighting we pay for. The Zeppelins won’t be over here directly; they are rather busy elsewhere at present.” [46]

In June 1915 the Somersets and Dorsets left Bath for ‘training under canvas’.[47]

In the same month the centenary for the Union Chapel was celebrated,[48]

In September the Medical Officer of Health asked that the Union Chapel burial ground be closed as it was insanitary and overcrowded and this was referred to the Home Office.[49] The Local Government Board replied that it would only close a graveyard in cases of danger to the public health.[50]

By January 1916 Prior Park was being prepared as a convalescent home for Canadian forces personnel. Bath Gas Company had to run a branch main to cope with the large number of extra fires and radiators that were to be installed.[51]

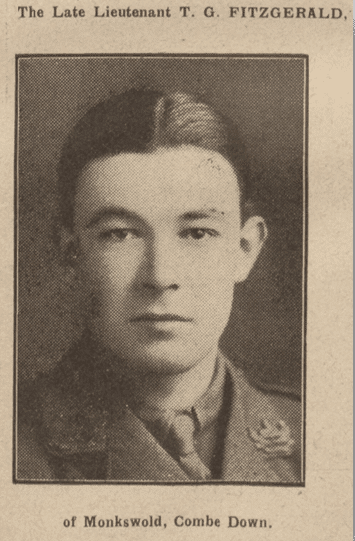

By now the ‘King and Country’ banner in the Bath Chronicle had been replaced:

The photographs were now mainly of the wounded and those killed, though reports of soldiers’ marriages featured too. Lieutenant Fitzgerald, who was 21 and serving with the Gloucesters, had been killed in action on 30th July. He had spent a year in the trenches and been mentioned twice in dispatches.

Sadly there were many more who were wounded or killed.

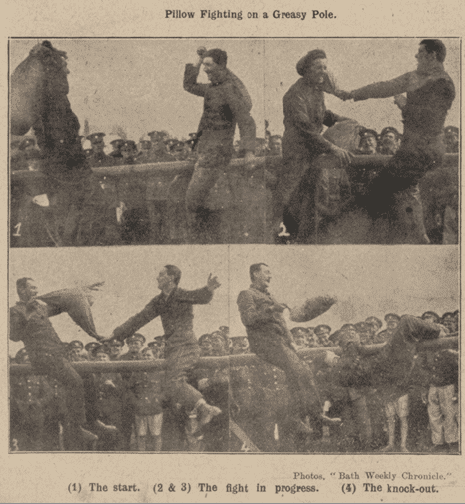

In May 1917 the military had a ‘sports day’ on The Firs. This included a donkey race – as two donkeys had been found grazing there – a ‘boat race’ using planks of wood, a tug of war, pillow fighting whilst sat on a greasy pole and an obstacle course race.

June 1917 saw an anti-German meeting in the Avenue Hall to establish a branch of the right wing British Empire Union (BEU) to fight ‘the enemy in our midst’.

The vicar of Combe Down, the Reverend Dr. Sweetapple, was in the chair with Lady Massie Blomfield, a vice president of the BEU, in support.

There was dissatisfaction with the way British prisoners of war (PoWs) had been treated compared to the British treatment of German PoWs. There was also dissatisfaction with ‘certain people in high places’ and a belief that a ‘great deal of evil had been done by not tackling the German question in England’. A sub paragraph was entitled ‘Germans must be fought as devils’.[52]

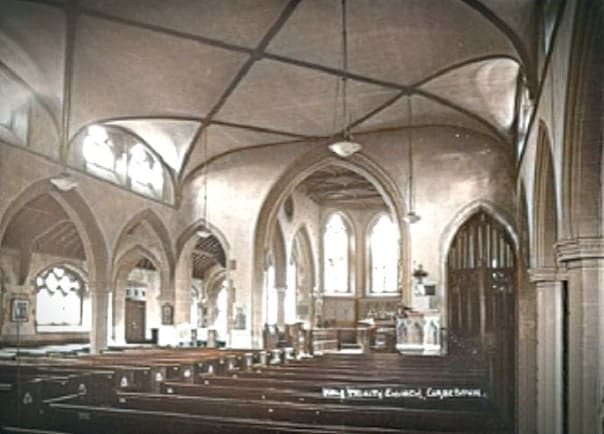

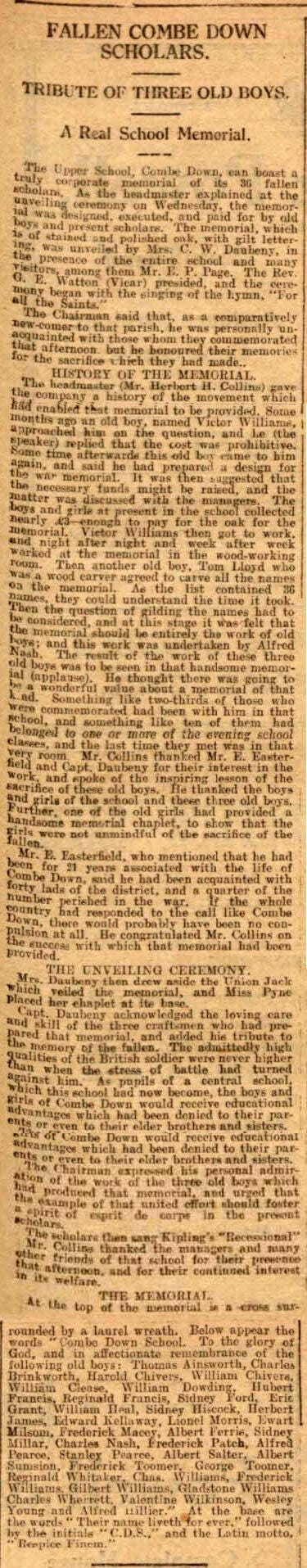

On 1st July 1917 a special service was held at Holy Trinity to commemorate the 23 deaths in service of men from Combe Down.

Despite the war other aspects of village life continued, with the Combe Down fete at the vicarage in August having several pages of photographic coverage in the Bath Chronicle.[53]

1918 continued in similar vein, but with newspaper reports giving a distinct feeling that there was, unsurprisingly, a level of war weariness. The headline in the Bath Chronicle on Saturday 16th November 1918 was ‘“The Greatest Day in History”: Bath’s Thanksgiving’.

Firs Field

In overcrowded Victorian cities parks were seen as a way of improving health and reducing discontent.

Parks were provided by the new municipalities and rich philanthropists and seen as a way of providing a venue for leisure time activities that were better than drinking or gambling.

An extension became recreation grounds allowing sports with a moral and codified framework which would stabilise and transform society.

The middle class used its business and organisational skills to establish clubs by pooling together members’ resources to purchase grounds and buildings for leisure activities.

The railways allowed sporting teams to travel and so sports like cricket, football and rugby began to be organised with agreed rules and national competitions but access to facilities was hard for those without money so once again municipalities and philanthropists helped out.

In 1894 Bath and County Recreation Ground Company was formed and The Rec came about.

The need for a recreation ground on Combe Down came to the fore and by 1897 Monkton Combe Parish Council, which then covered Combe Down, discussed the possibility, something that would continue for many years.

Consideration to purchasing The Firs was first made in 1904 but the question was how to fund the land purchase.

During WWI the question became more pressing and as the war progressed the notion of a memorial and help for returning servicemen took hold.

On Saturday 21 December 1918 the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette reported that Rev Alfred Richardson (1853 – 1925), Rev Dr Henry Darrell Sudell Sweetapple (1862 – 1953) and others purchased The Firs from the Misses Stennard for £750.

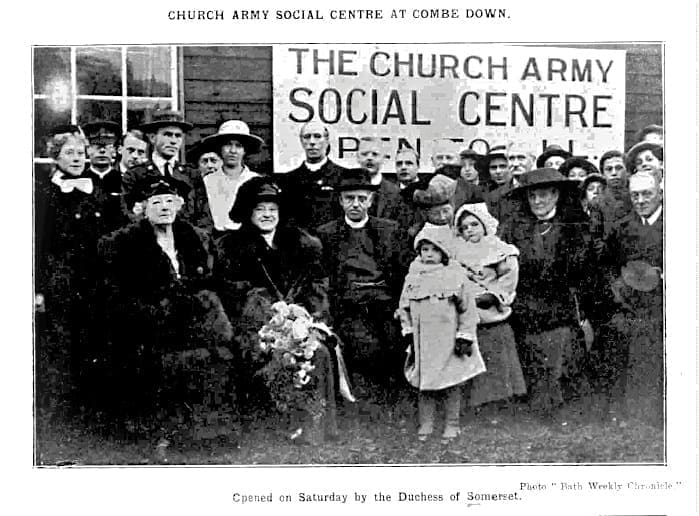

They proposed to gift it to the parish and the Church Army who would raise a hut as a the official Combe Down war memorial and keep some of the land for tennis courts and a bowling green.

A fund was established and on Saturday 4 October 1919 the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette reported that negotiations for the transfer were proceeding.

On Saturday 10 April 1920 the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette reported that £800 had been raised and the transfer could go ahead with all legal expenses paid.

On Saturday 24 January 1920 the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette reported that Monkton Combe Parish Council had formally accepted the gift on behalf of the parish.

So The Firs became part of Combe Down’s structure.

However in 2009 a proposal to allow The Firs (now owned by BANES Council) to become part of The Rec on ‘a long lease’.

There was much local opposition especially as it had been purchased by public subscription in the first place! There was overwhelming support that Firs Field be kept as an open space.

In 2015 Firs Field became a Centenary Field protected in perpetuity through a legal Deed of Dedication between the Council and Fields in Trust meaning that ownership and management of the site remain in local hands.

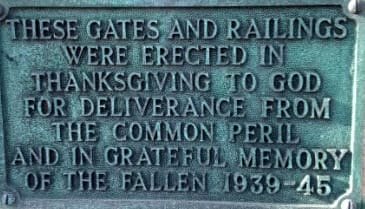

War Memorial

A meeting was held at Avenue Hall on 17th December 1918 to discuss a war memorial for Combe Down but no definite decision was arrived at though the Firs had already been bought for £700.[54]

At a meeting in February of discharged soldiers they voted for a “Church Army hut as a war memorial”.[55]

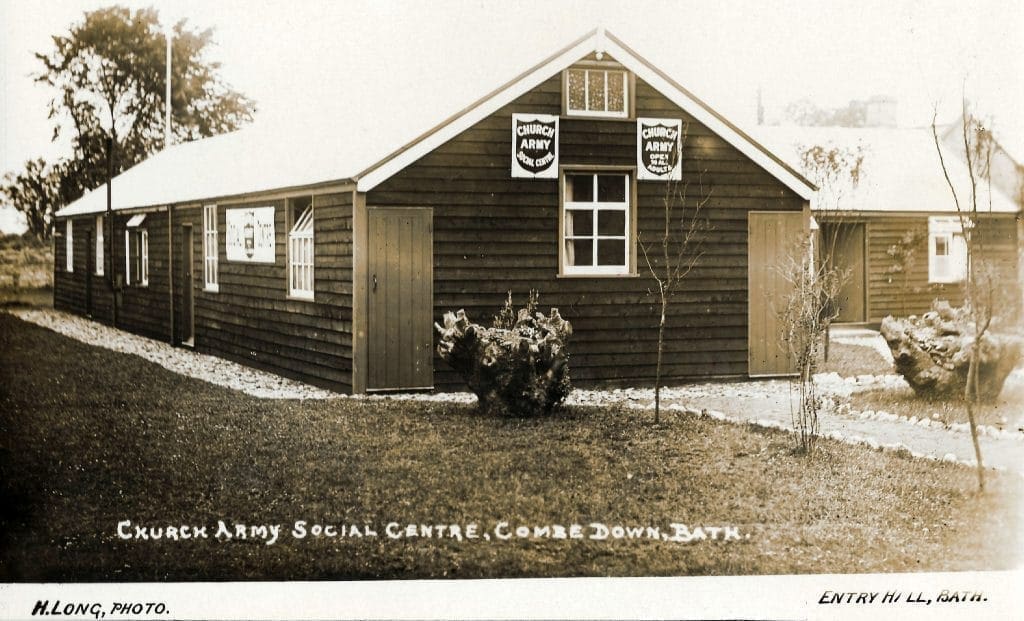

This was accepted and the Church Army hut became the official war memorial for Combe Down.

The location is, now, the home of the 10th Bath (Combe Down) Scout Group.

By June the grass had been cut to get the hut erected. By December the intention to lay out a bowling green, quoits pitch and four lawn tennis courts had been made at a parish council meeting.[56]

Some £300 was spent on this by August 1920 though £80 or £90 remained to be raised.[57]

In 1965 the wooden Church Army hut was replaced by the brick building used by the Scouts.

In the First World War, the Church Army worked at home and overseas providing recreation huts for the armed forces. At their peak these huts welcomed more than 200,000 men each day. Alongside this the Church Army also operated ambulances, mobile canteens and kitchen cars. Following the end of the war the Church Army opened training centres for men who had been left disabled by the fighting and the first Motherless Children’s Home was also opened.

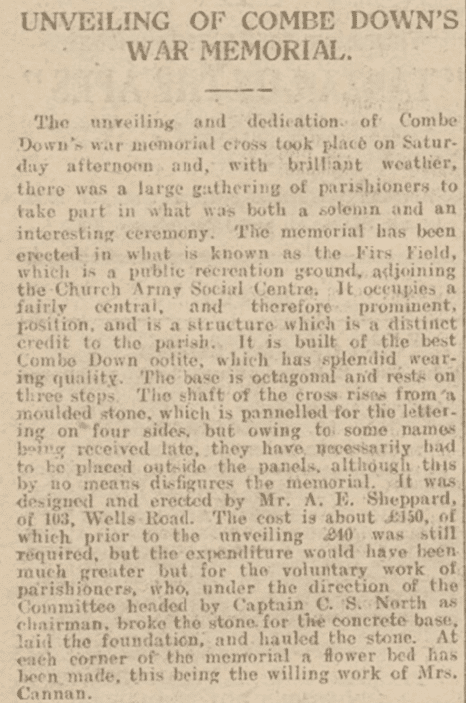

Ever since 1918 there had been a plan to have a stone memorial too. By 1921 a war memorial cross was carved and unveiled. It was officially handed over to the parish in August 1922.[58]

In November 25th 1922 three stained glass memorial windows, given by Mr. G. E. Cruickshank, were dedicated in Holy Trinity Church by Bishop Newham, son of the man who had been parish vicar.[59]

Unfortunately by 1924 the weather had obliterated the names of those listed on the memorial cross. It was decided to use metal plates instead.[60]

By the July meeting it was agreed that estimates should called for. [61]

After the Second World War things were a little more subdued. It was not until 1947 that it was agreed to add 16 names to the memorial cross at a cost of £51.[62]

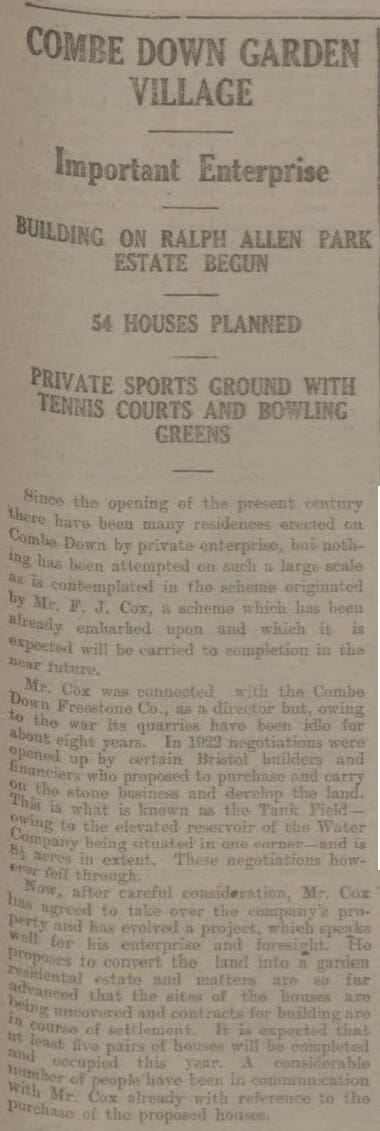

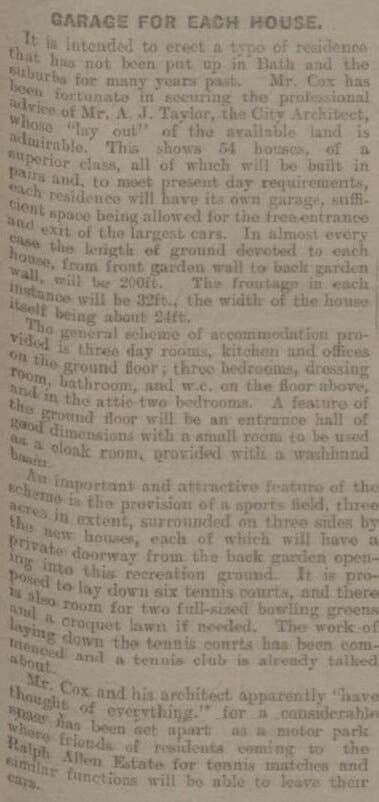

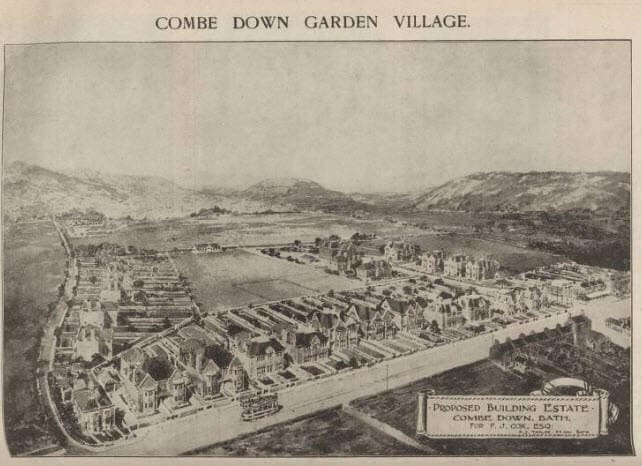

Garden Village

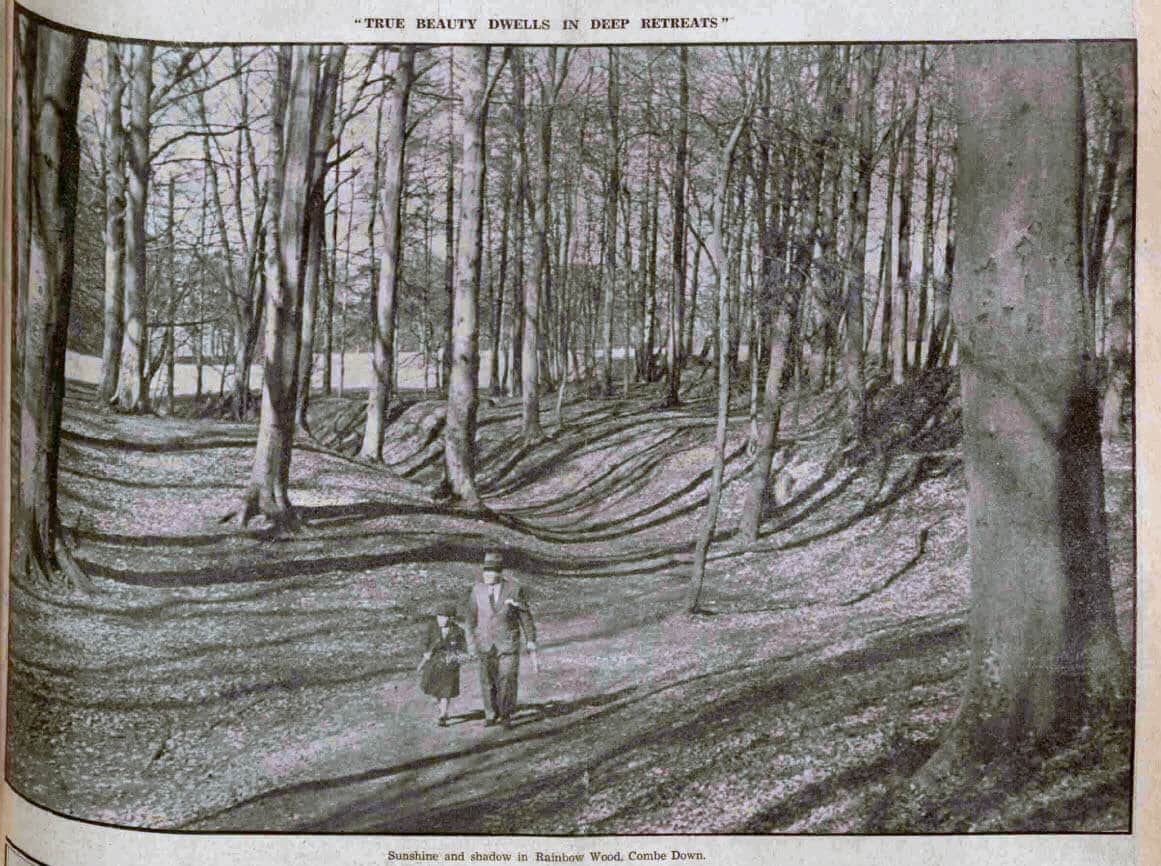

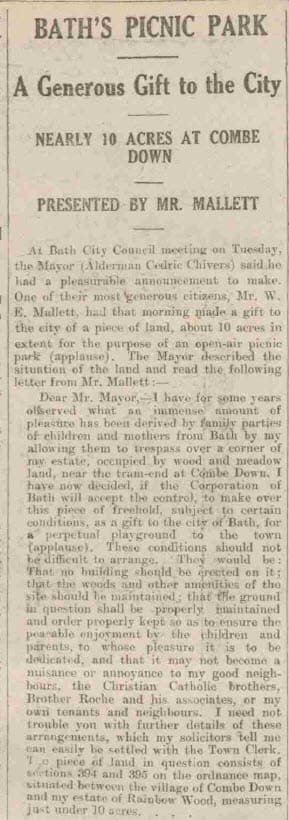

Rainbow Wood Picnic Park

Walter Ellis Mallett (1853 – 1929), who lived in Rainbow Wood House, gave ten acres of Rainbow Wood to the City of Bath in 1923 as a perpetual playground, to be enjoyed by the people of Bath forever. He said:

"I have for some years observed what an immense amount of pleasure has been derived by family parties of children and mothers from Bath by my allowing them to trespass over a corner of my estate, occupied by wood and meadow land near the tram-end at Combe Down. I have now decided, if the Corporation of Bath will accept the control, to make over this freehold under certain conditions as a gift to the city of Bath as a perpetual playground to the town. These conditions should not be difficult to arrange. They would be: that no building should be erected on it; that the woods and other amenities of the site should be maintained; that the ground in question shall be properly maintained and order properly kept so as to ensure the peaceable enjoyment by the children and parents, to whose pleasure it is to become dedicated, and it may not become a nuisance or annoyance to the Christian Catholic brothers, Brother Roche and his associates or my own tenants and neighbours....."

His daughters Margaret Mary Mallett (1882 – 1959) and Barbara Penelope Mallett Lock (1896 – 1978), gave much of the remaining land around Claverton and above Widcombe including Rainbow Wood Farm to the National Trust and fought successfully against plans to build houses on the land in 1948.

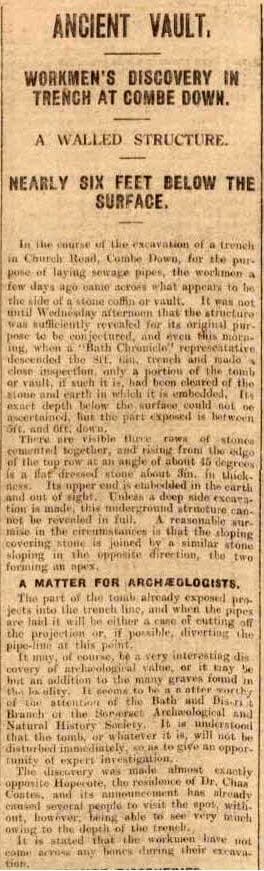

Secret Chamber

In 1925 a ‘secret chamber’ was found on Church Road just outside Hopecote. At first it was reported as a coffin, then it was speculated to be a culvert and eventually it was decided it was a secret powder magazine built by Ralph Allen.

The text below appeared in “Combe Down History”, material collected by members of the Combe Down Townswomen’s Guild during the winter of 1963 / 1964 and was from an ‘article which appeared in “The Bath and Wilts Chronicle”, Thursday, April 23rd 1925 Newspaper cutting supplied by Mrs. Smith, Hope Cote’.

BURIED VAULT RIDDLE THE MYSTERIOUS CHAMBER AT COMBE DOWN INTERESTING THEORY RALPH ALLEN’S POWDER MAGAZINE? BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE’S INVASION RELIC

The peculiar subterranean chamber discovered when cutting a sewer trench in Church Road, Combe Down, in front of Dr. Coates’s house, ‘Hopecote”, seems to call for more extended notice than has yet been given to it; for though it is not an antiquity it is a curiosity, with, probably, an historic association worth discussing.

As comparatively few people had an opportunity of inspecting the chamber whilst it lay exposed during April 16th and 17th, and as the opportunity of observing the ground conditions adjoining the structure through the deep-cut sewer trench – now filled up – will never happen again, it may be well to put on record particulars of the discovery, with the conclusions obtained by the evidence then visible.

The first discovery on April 8th, six feet down in the sewer trench, appeared to be the side of a masonry-built tomb, 17 ft. 4 ins. long, lying parallel with the trench and projecting nearly a foot into it. The sloping stone cover, 18 inches wide, was presumed to meet a similar stone on the unexcavated side to complete the tomb, and the tomb itself appeared to have walls 20 inches high built on a foundation of natural rock.

As excavation was not practicable, exploration by pick and crowbar was tried on April 16th, and it proved the masonry to be no sarcophagus but quite solid.

A FINELY BUILT VAULT

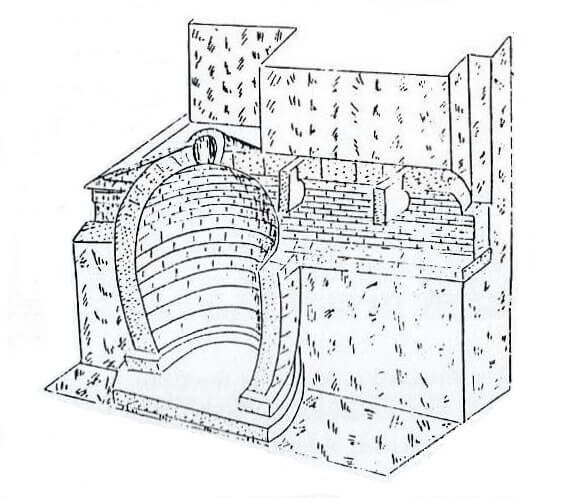

Further exploration of the same kind dispelled the next conjecture, that the structure was the base of a buttress, and, instead, showed it to be the top of a substantial parapet or roof, built to protect the dome of a huge barrel-shaped receptacle or chamber below, 17 ft. 6 ins. high by 9 ft. wide.

Entrance to this was obtained by enlarging the aperture sufficiently to allow descent to be made from the top by a ladder. Those who descended found themselves in a finely built vault, to all appearances unused as the builders had left it.

The apex of the domed roof was found to be furnished with a short neck-like orifice 15 inches wide, covered, in its present state, with a stone.

A remarkable feature of the building is a great arched culvert, or passage, about 4 ft. 6 ins. high which opens into the very top of the chamber on its eastern side.

Its floor is 13 feet up the side, and along its course are fittings for two doors five feet apart; it ends, after a few yards, in a mass of rubble with no sign of step or means of gaining the surface six feet overhead.

The walls of the chamber are about eight inches thick, but the masonry, though excellent, is not of a kind calculated to hold water, nor are there water lines inside where water has stood, nor any means for water to enter either at top or bottom.

CANDLE SMOKE CIRCLES

The sole evidence of human occupation reported by those who examined the interior were a few circles of candle smoke on the roof, and some stains on the bottom stones suggesting spilt port wine.

The rusty head of an ordinary carpenter’s hammer, broken from its shaft, was found lying on the floor and is now in the possession of the Clerk of the Works.

No rub or trace of the lowering of goods could be found under the passage entrance nor by the neck of the dome.

Mr. Wm. Clarke, who is in charge of the Combe Down sewage works, made a sketch of the chamber, and obtained careful measurements of the interior before it was closed up again; and the investigation that was made is entirely due to the interest that he took in the discovery.

The building remains in situ, lying close between the line of sewer pipes in the road and the wall of “Hopecote” – a yard or so westward from the eastern boundary pillar of the front garden. The passage runs somewhat under the pavement north-east towards the enclosed garden of “Hopecote”. The sewer pipes are laid between eight and nine feet deep under the projecting eve of the parapet first discovered, not quite touching the wall of the chamber in passing.

No extensive inspection of the exterior of this curious building was possible beyond ascertaining that the sloping stone of the parapet was the first course of a strong roofing over the dome, and that the slabs of stone which had seemed foundations were really placed over the dome, apparently to help to throw surface water away from the bulging sides of the building.

THEORIES

The problems of the construction of this mysterious chamber, and the use of it are solved to some extent by the observations rendered possible by the trenching then open, and the conclusions I have reached are these:

- The building was erected against the eastern side of an open quarry-working. This was shown by the unbroken ground up to it on the east that the trench cut through, with the ancient turf line two feet down still intact; while the trench on the west was cut through entirely “made-up” ground of quarry rubble, ending with a cavernous entrance to underground workings disclosed west of “Hopecote” house.

- The chamber was erected with the purpose of its being buried in quarry rubble; as is shown by its barrel shape and the domed top – both designed to resist external pressure – and by the great slabs of stone on which the protective roof is built, which could not have been laid on the dome before it was buried up to its shoulders in rubble.

- Great precautions were taken to protect the chamber from the west, and that aim was effectively secured.

- Its proportions would just allow of a ladder being brought down the passage and lowered when entrance into the interior was desired.

- The lantern orifice in the dome was sufficient for the illumination of the interior by day without other light, but was not large enough for the purpose of raising or lowering goods or liquid through it.

- Apparently the building was abandoned unfinished, for there are signs that the passage was not completed, nor doors to it furnished; nor was the parapet visible in the trench finished off at its eastern end.

OBJECT OF THE CHAMBER

As to the purpose of the chamber, the traces of Ralph Allen are obvious.

The site of it is where he had his earliest quarries, as is shown by Thorpe’s 1742 map ; and his history supplies a reasonable explanation of the rest of our problem.

Ralph Allen began his quarrying in 1729, and in 1745 he had completed his Prior Park Mansion. In that year came the Young Pretender’s invasion, and Ralph Allen, in support of the King, raised and equipped 100 volunteers.

The whole country was in alarm at the peril of renewed civil war, and we can see that Ralph Allen may well have needed in haste a safe powder-magazine. This could have been erected speedily by his army of workmen in his bit of worked out-quarry not too near his mansion.

It might, too, have been erected secretly and made invisible to an enemy among the rubble of the quarries, for Combe Down was then a desolate wilderness, with no houses except a dozen or so of cottages for the quarrymen.

However quickly the magazine was built in this emergency, the need for it passed away before it was quite finished, and it was abandoned – even as George the Second’s preparations for flight back to Hanover were abandoned when Prince Charlie’s march on London was arrested at Culloden in 1746, and the invasion came to a sudden end.

RELIC OF NATIONAL PANIC

These circumstances fit well with the appearances of the recent discovery, and according to this interpretation of the evidence available the people of Combe Down have in this vault a relic of a great, though passing, national panic; and an evidence of the silent, unassuming wisdom of the great man who helped to build modern Bath.

The drawings and measurements made by Mr. Clarke should be of public interest if he will publish them; and the observations here recorded can be verified by eye witnesses and the workmen who took part in the exploration.

Those who descended into the chamber to examine it include, besides Mr. Clarke and the workmen engaged on the works, Mr. Flower, the contractor; Mr. Gerald Grey, Mr. N. V. H. Symons, and a few others, but not many people secured access to it during the brief time that it was open.

Electric Lighting

Combe Down had been lit by gas light since 1865. In 1924 a petition to install electric public lighting to the 32 lamps was received by the Electric Lighting Committee of Monkton Combe parish council. It was discussed but a decision not to proceed was taken.[63]

By 1926 things had changed somewhat and the Clerk was instructed to invite tenders to light the now 38 lamps from both the gas and electric companies. In 1927 the decision was taken to move to electric public lighting.[64]

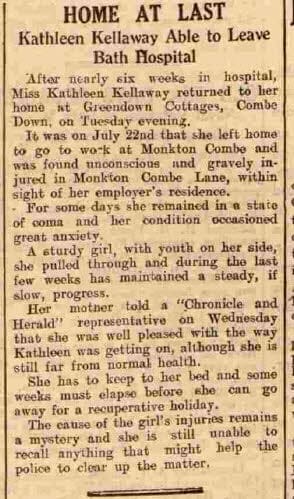

Kathleen Kellaway attack

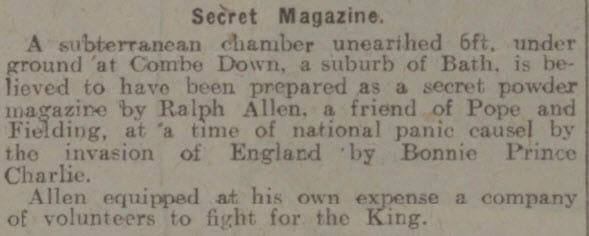

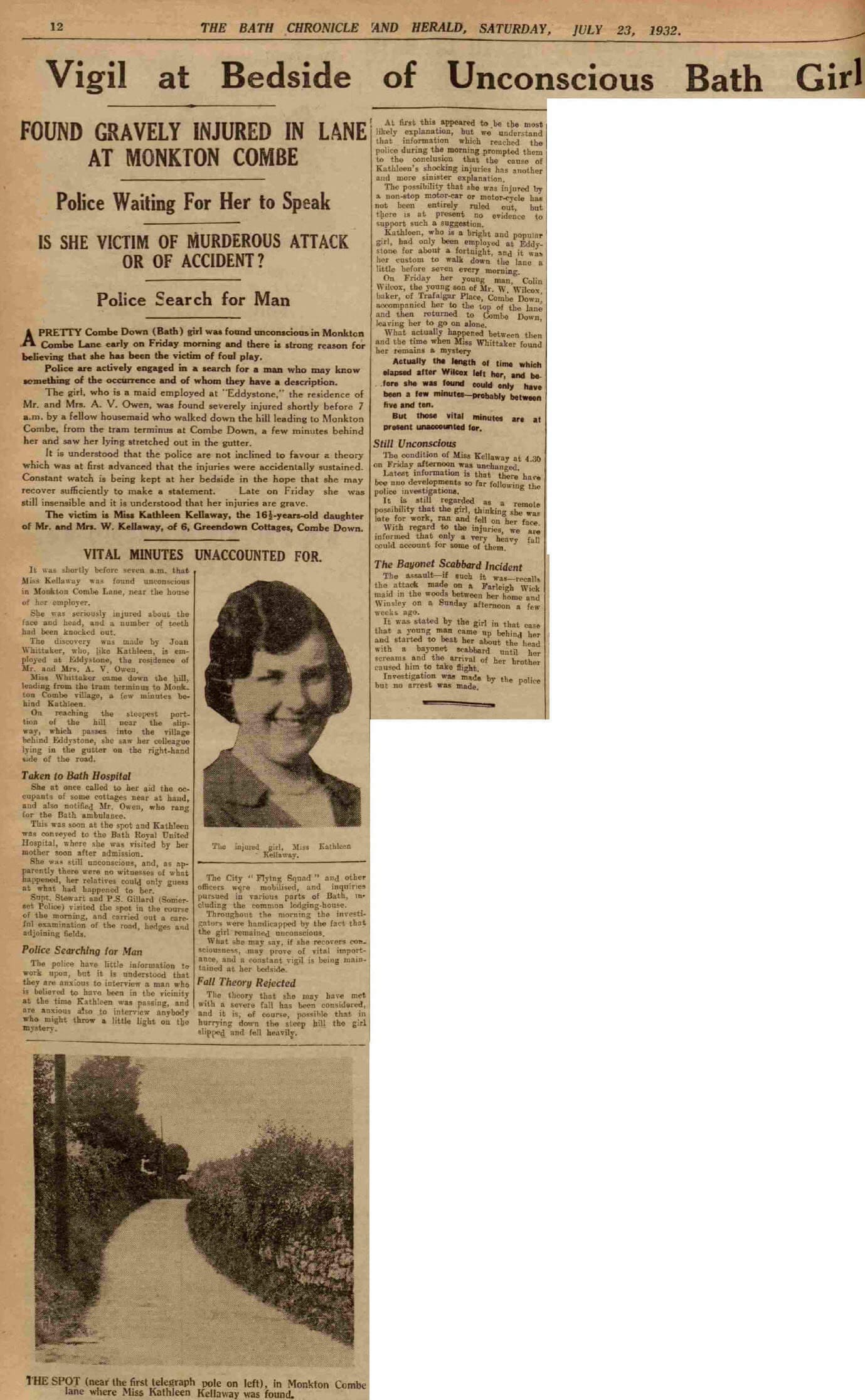

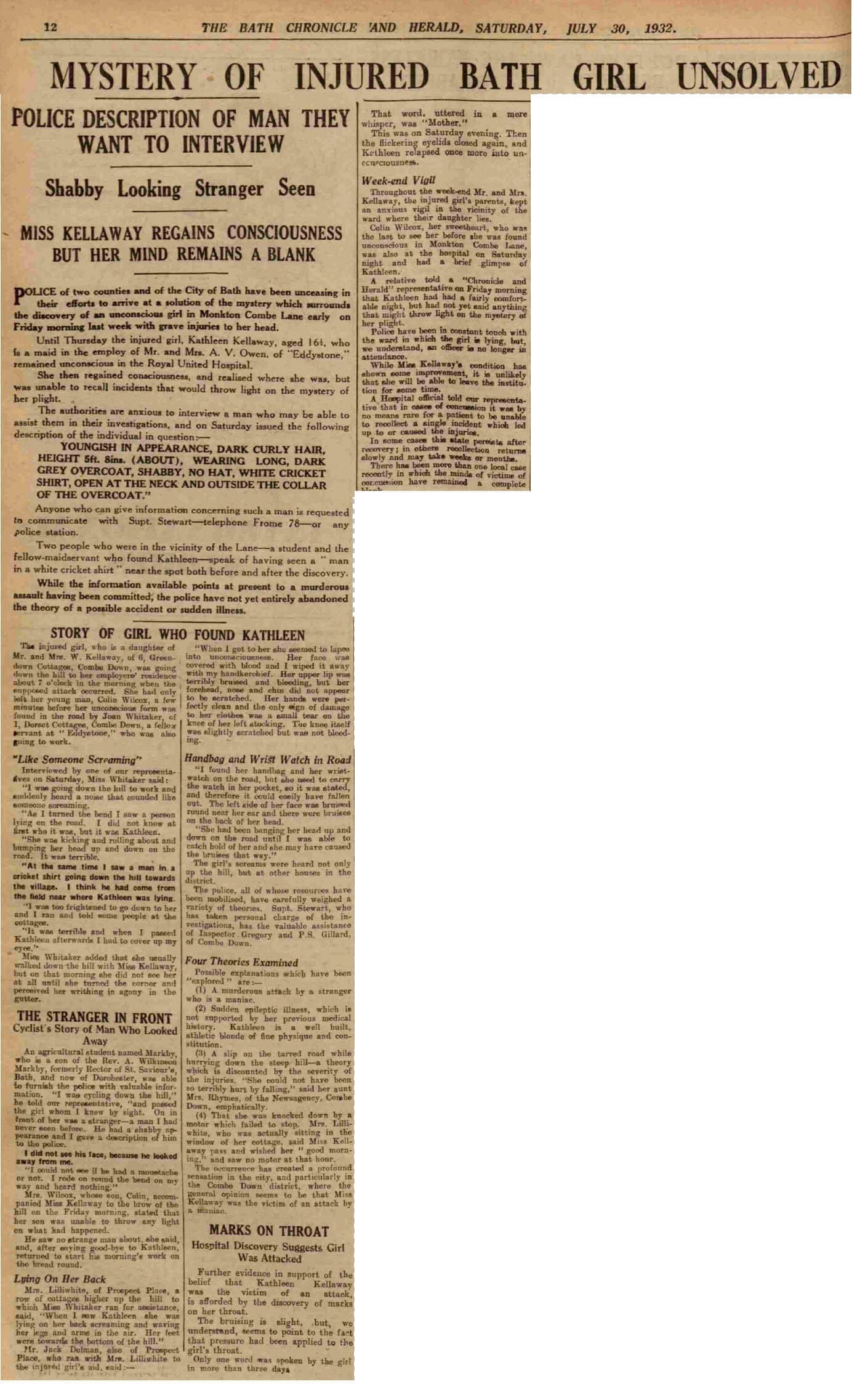

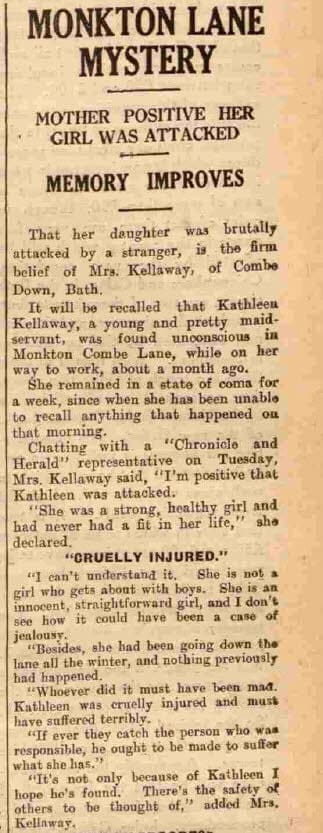

In July 1932, Kathleen Kellaway (1916 – 1992) was attacked whilst walking down to Monkton Combe. No one was ever caught.

I have decided that the best way to present this is just to show the relevant articles from the Bath Chronicle. In May 2020 her cousin, Frank Sumsion (b. 1926) told me:

"I was talking to a relative from New Zealand regarding this only a few days ago. I was only six years old at the time of the assault but was aware of something serious going on. It was not until later years that I was told the seriousness of the attack, and that no one was ever brought to justice. Kath was unable to have children so we can only assume it was worse than reported, we shall never know. I do know she was a lovely person and worked extremely hard with Colin Wilcox and they were a very happy couple. I still remember Colin and Kath attending the dances at the Church Rooms in the Avenue during the war. Kath wore lovely dresses that my sister envied. I don’t know where the material for them came from, they may have been hand downs from my aunts’ on the Down."

World War Two

The Admiralty moved about 4,000 personnel to Bath in September 1939.

The majority of their staff worked in the centre of Bath in the Pump Room, the Empire, Pulteney and Fernley hotels, the Domestic Service College and Kingswood School.

After the war, in 1949, it was announced that another 1,500 civil servants were to come to Bath and that Oldfield School, BRLSI and the Holburne Museum would be taken over.[65]

The new science block part of Prior Park was also taken over and the government acquired land by Foxhill which was the agricultural land of Springfield Farm and said that ‘hutments’ would be placed there.[66]

By 1940 a new type of building, the Temporary Office Building (TOB), had been designed by Sir James West for the Ministry of Works.

This was of a steel frame, single storey brick and concrete construction with a central spine, central reception area and twelve wings. The corridors within the spine were made wide enough such that the building could easily be converted into a hospital, or other premises should the need arise.[67] Some of these ‘hutments’ were constructed on about 46 acres at Foxhill from March 1940.[68] Foxhill hutments were labelled Blocks A to G and the pub opposite, the Forester’s Arms, quickly became known as Block H.[69]

In February 1947 it was proposed that Navy Accounts, Supply & Maintenance, Civil Engineer-in-Chief and Expense Accounts departments with about 4,000 staff would remain in Bath.[70] In March 1947 this was confirmed as something the Admiralty wanted.[71]

In 1948 final confirmation that they would stay was given.[72]

By 1958 after the Nihill Committee, set up in 1956, reported, it was decided to reorganize the design of naval vessels and a number of departments (Mechanical Engineering, Naval Equipment, Naval Production) were combined in a new directorate of naval ships based at Foxhill.[73]

By 1962 the situation was that:

“The Admiralty Offices in Bath and the occupying departments are as follows: Foxhill — Director General Ships; Director of Armament Supply. Ensleigh — Director General of Weapons; Director General of Dockyards and Maintenance; Director of Contracts (part); and certain secretariat and accounting units. Warminster Road — Principal Director of Accounts (part). Empire Hotel — Certain Secretariat and Common Services units. Superintendent of Admiralty Material Standardisation. 1 Pulteney Street — Principal Director of Accounts (part). James Street, W. — Director of Stores (part) providing garage for Admiralty vehicles. The sites at Foxhill, Ensleigh and Warminster Road have a number of separate buildings of the "hutments" type. The long-term aim is to concentrate all Admiralty staff in Bath on one site and to relinquish the surplus hutments and other buildings. Discussions have taken place with the Ministry of Works about the possibilities of making a start on this.” [74]

In 1971 the Admiralty was ‘merged’ into the Ministry of Defence (MoD) with Foxhill being a part of the Procurement Executive.

Staff in Bath continued to be at the centre of the country’s defence work, administering naval bases, overseeing logistics and designing ships, including the battleship Vanguard and the first aircraft carrier called Ark Royal as well as, in Block C, nuclear submarines and missiles.

By the 1990s the MoD had evolved and decided to build a new 130,000 square metre building on a 98 acre site at Abbey Wood in Bristol which opened in 1996.

The Defence Procurement Agency (DPA) and Defence Logistics Organisation (DLO) were established in 1999 – 2000 and merged in 2007 to become Defence Equipment and Support.

It was decided to transfer all Bath staff to Abbey Wood and, in March 2011 after 72 years, the Admiralty / MoD left Bath and Foxhill.[75]

In 2013 the MoD announced that Curo, a non profit housing organization managing 12,000 homes in the area, including many on the adjacent Foxhill estate, had bought the site for a mixed use development of 700 homes to be called Mulberry Park.

Admiralty

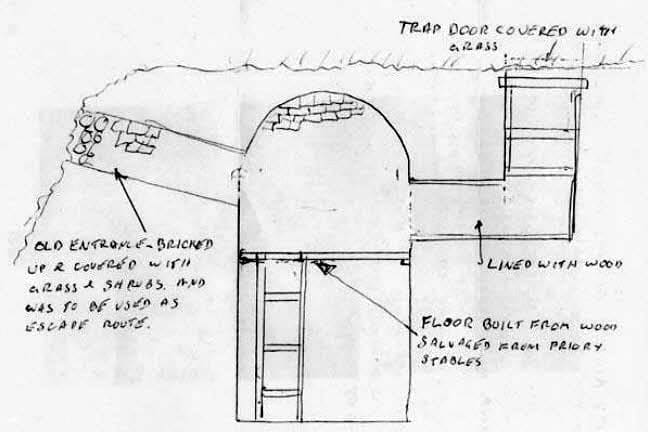

Prior Park also had Admiralty Patrol Units, part of the Auxiliary Units of the secret resistance organisation under the control of GHQ Home Forces.

Auxiliary Units were a network of trained volunteers prepared to be Britain’s last ditch line of defence during World War Two.

They operated in a network of cells from hidden underground bases around the UK. Each patrol had designated targets and operated from a specially prepared hideout. The icehouse in the grounds of Prior Park was the base for No.4 Patrol, G.R.761635.

Notes on AA4 by R W Bennet

…We prepared our O.B.s. My patrol was very lucky in this because in our area was a mansion surrounded by a considerable estate (Now National Trust property) and in the middle of a plantation was a disused icebox which once stored the food for the house. You entered by a tunnel some four feet high stone lined cut into the hillside and this led into an underground chamber roughly eight feet in diameter and possibly twelve feet deep, We first had to completely conceal the main entrance and then dig two escape tunnels in case of surprise. We floored this with wooden floors and built in bunks and shelves. Wood of course was impossible to obtain because of the war and quite literally we stole what we needed. We didn’t call it stealing. It was ‘acquiring’. We also ‘acquired’ oil lamps to work by. H.Q. gave us some three months of tinned rations which we stored there. Our explosives and ammunition were stored quite a bit away in steel and concrete bunkers built by the army. Our fellow patrols were not so lucky as we and had to dig their O.B.s. from scratch. Fortunately the local terrain is very hilly so they did not have to dig vertically as some had to in other parts of the country.

The matter of secrecy was an obsession. It was dinned into us that we told nobody of our duties, training or organisation above all our own wives or families as the Gestapo would have no hesitation in torturing them to get information about us….

…Quite late in the war we were discovered by two enterprising pupils of Prior Park School who seeing all our tinned stores thought they had stumbled on a black market cache and reported their find to their head master who reported us in turn to the owner of the property who in turn called in the police. We found ourselves on a raft of charges from simple trespass, alterations to property without permission, damage to property, theft of timber (from his stables) and heaven knows what else. Our I.O. came up from Taunton and put it alright. The old Gentleman was a retired Lt. Colonel and when he was put into the picture gave us his blessing and carte blanche to help ourselves to anything in the stables which we needed.

And we thought we had disguised the O.B. so well. It was fortunate that our ammo and explosives were all stored in a separate dump against that very happening. As the risk of invasion was considered to be more or less over by then we did not have to find another location….

Bath Area Auxiliary Units – Bob Millard

Excerpt from Bath Blitz Memorial Project by Ron Frost

I was 11yrs old and the year was 1940. My two brothers, Tony and Dennis and myself were attending Widcombe Junior School. Our summer holidays that year were overshadowed by talk of the believed inevitable invasion of Great Britain by the German forces. France had fallen and the Battle of Britain was taking place.

At our ages it was both an exciting and scary time. I can remember the local Home Guard being very active at that time, but everyone tried to carry on as normal as possible. It could not have been easy for most adults in those uncertain days.

We were all aware that a German invasion was likely because we had witnessed the Home Guard and the Air Raid Wardens carrying out their training. Heaps of stone and timber had been spaced at intervals in the fields to foil the enemy gliders and paratroopers, and there were road blocks everywhere. I used to read the daily papers avidly in those days, about the bombing of London and other cities.

At 11 years of age I was the eldest, my brothers being ten and eight. One of our favourite ‘playgrounds’ at that time was Prior Park gardens. We and our friends played on the lake and in the woods regularly. When the staff and pupils were on their August vacation, we were left free to roam. There was in those days, an old punt at the side of the lake. We used to cut sticks from the woods, sharpen them to a point and try spearing fish from the boat, (we never caught anything). The punt had a leak at one end so we made our young friend Robert stuff one of his socks into the hole and also used a tin can to bale the water out.

We could also swing from the creepers that hung down from the trees, playing at being ‘Tarzan’. You might say that this was how this particular event came about. It was whilst we were swinging around in the woodland that my brother Dennis, scraping his foot along the rough ground, exposed part of an iron ring in the undergrowth. On clearing away the earth, we found the ring was attached to a wooden hatch cover.

Of course, being curious we pulled the cover up and discovered a deep shaft with a vertical wooden ladder going down about ten feet. More and more intrigued we went down the ladder and at the bottom was a dug out room measuring about 8ft by 5ft. At one end of the room was a table and on it, in the gloom, Tony found a storm lantern. I always had matches in my pockets in those days so I lit the lantern.

We looked around in great surprise. There were chairs around the table, and along one wall were about four bunk beds. The biggest shock we had though was discovering guns and ammunition in boxes along the opposite wall. Then Tony shouted, “Hey, this lamp was made in Germany!” There it was clearly stamped on the lamp. So that was it, we had discovered a German spy hideout! But what were we supposed to do? Well we all decided that we had to inform the police. The newspapers were full of stories about German sympathizers in those days, called “Fifth Columnists”. I thought we had discovered one of their spy holes.

So, covering up the pit and hiding it as before, we set off. Bath Police Station was in Orange Grove in those days, next to the Empire Hotel. It had formerly been used as the Fire Station. All four of us crept into the front office of the station. We could just about look over the counter at a police sergeant who looked, to us, about ten feet tall. “Well, what do you lads want?” He bellowed. “Please sir, I think we have discovered a German spy hideout” I said to him. “Oh yes, and where is this hideout” he said.

So we explained what we had found at Prior Park, and by this time quite a few more policemen had gathered around us. We must have been quite convincing because, although they didn’t have a clue about what we were telling them, they contacted our parents to let them know where we were, then took us in a police car back to Prior Park. Having proved to them that we had indeed found a secret hideout, they took us back to a waiting room at the station.

After a little while, we were interviewed again in the presence of Major Lock, who was the officer in charge of the local Home Guard. We knew of him because he lived in a house on Widcombe Hill. But the Major admitted that he was also unaware of the hideout we had found. Eventually we were allowed to go home after solemnly swearing that we would not divulge anything about the whole affair. And also vowing that we would not go into Prior Park woods again. Of course, our parents had to know what had happened and they must also have been cautioned to keep mum about it.

All of us involved in this escapade kept our silence about it, and in fact, it remained almost forgotten for nearly fifty years. Only in recent years have we mentioned anything, after the story of Winston Churchills’ secret army came out. An informal army of local, trustworthy, and countrywise men and women was formed to harass the enemy had they actually managed to invade the British Isles. About two years after this episode, we did return to the woods at Prior Park, but were unable to find any evidence of the hideout.

Excerpt from Bath Blitz Memorial Project by Ron Frost

There were also Admiralty Units at Kelston Park, Langridge, Warmister Road and Newton Park. There were other units at Swainswick, Bathampton, Weston, Englishcombe and Southstoke.[76]

The British Resistance Archive states:

“Around 3,500 such men were trained on weekend courses at Coleshill House near Highworth, Wiltshire, in the arts of guerrilla warfare including assassination, unarmed combat, demolition and sabotage. Recruits for Coleshill reported to the Highworth post office, from where the postmistress Mabel Stranks arranged for their collection. Each Patrol was a self-contained cell, expected to be self-sufficient and operationally autonomous in the case of invasion, generally operating within a 15-mile radius. They were provided with a concealed underground Operational Base (OB), usually built by the Royal Engineers in a local woodland, with a camouflaged entrance and emergency escape tunnel; it is thought that 400 to 500 such OBs were constructed. Some Patrols had an additional concealed Observation Post. Patrols were also provided with a selection of the latest weapons including a silenced pistol or Sten and Fairbairn-Sykes "commando" knives, quantities of plastic explosive, incendiary devices, and food to last for two weeks. It was not expected that they would survive for longer. Members anticipated being shot if they were captured, and were expected to shoot themselves first rather than be taken alive. The mission of the units was to attack invading forces from behind their own lines while conventional forces fell back to the last-ditch GHQ Line. Aircraft, fuel dumps, railway lines, and depots were high on the list of targets, as were senior German officers. Patrols secretly reconnoitred local country houses, which might be used by German officers, in preparation.”[77]

Leroy Henry

About midnight on 5 May 1944, at The Old Post Office in Church Road on Combe Down, Douglas Thomas Lilley (1908-1978) and his wife Irene Maud née Lyne (1910-1999) were woken by a tapping on their bedroom window.

They went to the front door and saw a black American soldier. His name was Leroy Henry, a 30 year old truck driver from St. Louis, Missouri, stationed at a US base at Southstoke.

Irene Maud claimed he said he was lost and asked the couple if they could help guide him back to camp.

In her statement to the police she said she had agreed to walk some way with him until he recognised the way back. He then escorted her home again but when they were halfway, produced a knife, forced her over a wall and raped her.

When she did not return, her husband said he went out looking for her and found her in a ditch by the side of the road and called the police.

The police took them in a car to a doctor. On the way, the car came across Henry walking along the road. Lilley identified him and Henry was arrested two hours later.

His interrogation by US Military Police supposedly brutal. He was kept standing for hours on end and when he fainted from exhaustion was kicked and beaten.

Henry signed a confession and was taken to Shepton Mallet prison, then being used by the American military charged with rape.

Under US military law, this was a crime which carried the death penalty.

Three weeks later at Warminster, Henry was found guilty of rape by a US court martial and condemned to death by hanging.

Only hours after he was returned to Shepton Mallet prison another black inmate was hanged for rape and some days later another black man was shot for the same crime in the prison courtyard. Some eighteen American servicemen were executed at Shepton Mallet prison during the war. All but four were black or Hispanic.

When news of the conviction appeared in the Bath Chronicle, many local people were troubled. Most of the British press expressed outrage at the hastiness and severity of Henry’s conviction. Alderman S Day, a Bath magistrate, and Jack Allen, a local baker, started a petition against Henry being executed. Within weeks it gathered 33,000 signatures in the Bath area.

The case against Henry was also starting to fall apart.

A medical examination of Irene Maud indicated that she had sex, but there were no signs of a struggle.

He claimed that his confession had been written by a police officer.

Then it emerged that Henry regularly visited a couple of the local pubs and had met the woman twice before and on both occasions had paid her £1 for sex.

On the night of the alleged rape he had asked to see her. She told him her husband was at home, but that he should knock on the window and she would sneak out with him. His claim was that this time she had demanded £2 from him. This was more money than he had on him, but he gave her all the money he did have, which was more than £1, but less than £2. She threatened to get him into trouble.

Henry had no previous convictions and a “very good” record of service, according to his commanding officer,

Despite the coming Normandy invasion, Commander in chief Dwight D Eisenhower was forced to pay attention to the case in the first days of June as it became an international cause célèbre.

The evidence against Henry was unsafe and on June 23 1944, the case against him was quashed and he was freed on the direct orders of General Eisenhower.

Foxhill

There had been concerns about housing in Bath and on Combe Down for years but, before the Second World War, the government would not sanction loans to local authorities for housing if it was felt that they could be built by private builders.[78]

Because of the war house building slowed to a virtual standstill between 1939 and 1945.

After the Second World War poor housing and overcrowding was to be tackled based on the Beveridge report of 1942, by Sir William Beveridge (1879 – 1963), which said that the government should find ways of fighting the five ‘Giant Evils’ of ‘Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness’.

#To tackle ‘Squalor’ the government aimed at building 200,000 new houses a year.

By 1944 the 26½ acres at Fox Hill adjoining the Admiralty had been zoned for 250 houses[79] although this was “dropped” owing to objections[80], though the idea was soon raised again.[81]

By October 1945 it had been agreed to allocate 140 Uni-Seco prefabricated houses to Fox Hill and Cotswold Road.[82]

The Uni-Seco was a two-bedroom flat-roofed bungalow with a resin-bonded plywood timber frame and asbestos wall sections with dimensions of 23′ 6″ by 19′ 7″, and included the Ministry of Works standard kitchen/bathroom service unit, plus a lounge made by Selection Engineering Company Ltd.

Delivery commenced in May 1946 and the site was to be called Bradford Park.[83]

During the 1950s and 1960s the Foxhill area was redeveloped as council housing.

Pew rental abolished

The Act of Uniformity 1558 made attending church compulsory. Compulsory attendance was repealed during the Commonwealth but returned with the Restoration in 1660. The law was, fitfully, enforced well into Victorian times, and indeterminate imprisonment for non payment of the fine became common enough to raise a scandal in Parliament in 1842. Final abolition was not until 1888.

Churches were not commonly furnished with permanent pews before the reformation.

Stone benches appeared in the thirteenth century, placed against the walls of the nave. Movable wooden benches replaced stone ones from the fourteenth century and became more common in the fifteenth.

With the rise of the long sermon, after the Reformation, the pew became a standard item of church furniture.

During this time the allocation of a church’s pews showed the social hierarchy within a parish. Certain areas of the church were considered to be more desirable by offering a better view of services or by making a certain family or person more prominent or visible to their neighbours.

.In some churches there was no public seating and pews were purchased from the church and the price of the pews went to the costs of building the church. These pews were personal property. Pew deeds recorded title to the pews, and were used to convey them. When pews were privately owned, the owners sometimes enclosed them in lockable pew boxes.

Pew rental was also common, until the mid twentieth century, as a means of raising income. Pew rental became a source of controversy in the 1840s and 1850s. The legal status of pew rents was felt to be questionable.

The evidence indicates that the primary renters were from the middle and lower middle classes, particularly small business owners.

In December 1949 it was decided that Holy Trinity would abolish pew rental from January 1 1950.