Combe Down

Combe Down

Combe Down was still a small outpost of Bath. At the beginning of the century there were probably less that 200 – 300 people resident on Combe Down and in Monkton Combe[1]. Clearly houses were being built but other information is quite scarce.

But, by 1841 Combe Down had grown considerably and had two churches and a school. The 1841 census shows, by my count, 149 properties. The enumerator counted 162 households with 362 males and 435 females giving a total population of 797. So a large jump from 100 or so, but Combe Down is still quite a small place. It continues to grow with new housing during the 1840s.

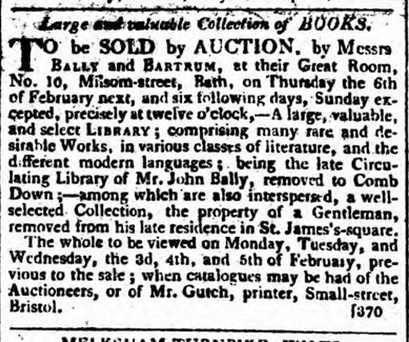

From an 1812 advert in the Salisbury and Winchester Journal we see that Mr. Bally had brought some of his books up on to Combe Down.

William Bally had his circulating library at number 11 and then 12 Milsom Street. He ran it from 1768 until he died in 1774. His widow took charge of the library until it was purchased by Joseph Barratt in 1782. In 1794 William Bally’s son, John, took it over and ran it until 1811, when he sold it to C. H. Duffield, though it seems from the advert that he did not sell all the stock.

Other than this, and the odd death and serious affray, little was reported about Combe Down from 1800 – 1820.

The serious affray was reported in the Salisbury and Winchester Journal on Monday 17 August 1818.

It reported that on Saturday 8 August 1818 a drunken Mr. Platt returned home, thought that his neighbours were insulting him and fired a blunderbuss at them. He injured two, whereupon they attacked and beat him ‘most unmercifully’ not realizing the blunderbuss had exploded and mangled his arm.

When they did realize they called a surgeon who amputated the arm. At the time of the report he was still ‘suffering severely’. There are more reports from 1820 onwards but most are births, marriages deaths, houses to let or for sale as people leave or die, and the odd quarry accident with appeals to help the widow and family.

One excitement was a Methodist camp meeting on 25 May 1828. The preachers ‘including 3 females’ brought a letter to the Bath Chronicle on Thursday 5 June 1828 about the meeting which the writer stated that:

‘…the female preacher on Combe Down perverted and debased the comfortable and pure doctrine that the heart may be turned through repentance and faith, and divine grace, to the belief and practice of true religion, by the degrading, common place, vulgar practice of holding up of hands and then, in certainly a blasphemous manner, deciding that to all such Christ was precious….’

and more in this vein. It is unsigned.

After this, other than the apparent suicide of Elizabeth Morris, ‘a young woman in the Service of Miss Aslett’, reported in the Bath Chronicle on Thursday 5 June 1845, a sad story and the announcement that The King William was ‘to be let or sold’ on Thursday 11 September 1845 nothing other than ‘normal business’ occurs.

De Montalt Mill

De Montalt Mill

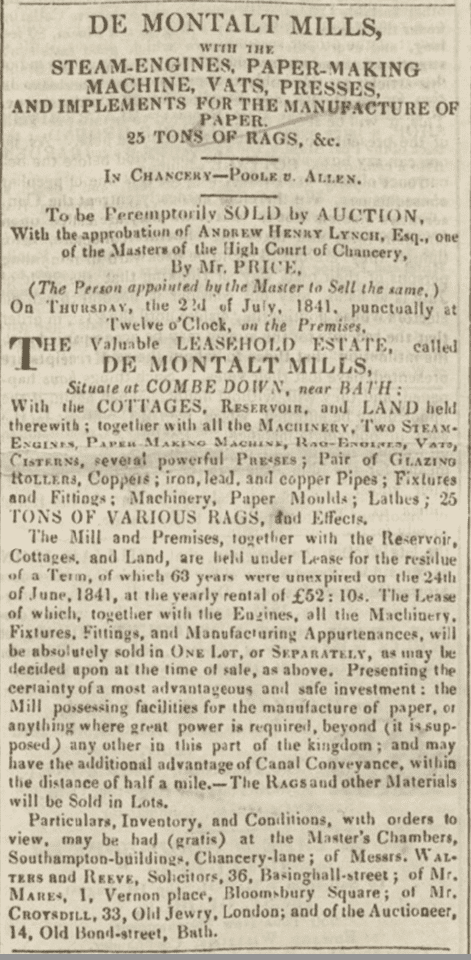

On Thursday 8th July 1841 an advert appeared putting everything at De Montalt Mill, built in about 1805, up for sale.

It had manufactured high quality paper, used by the great painter J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), under the partnership of John Bally (1773 – 1854), William Ellen (1781 – 1832), and George Steart (1770 – 1837) which lasted from 1805 until early 1830s at which time they seem to have sold to William Jennings Allen (1807 – 1839).

It had the largest water wheel in England at 56 feet.

Although it has been suggested that it became a gutta percha factory in 1834[9] this is impossible as gutta percha was only introduced to the West by William Mongomerie in 1843[10] when he demonstrated to the Royal Society of Arts in London, the materials’ ability to be heated and moulded.

William Jennings Allen (1807-1839) was a wholesale stationer and it is far more likely that he saw an opportunity to continue paper making – after all that’s what all the machines did! The advert in the Bath Chronicle also suggests this.

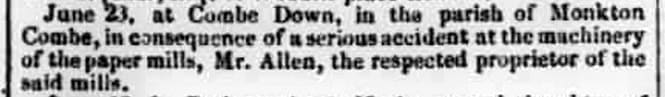

Unfortunately he died in an accident at the mill and the case ended in Chancery:

"PURSUANT to a Decree of the High Court of Chancery, made in a cause Poole versus Allen, the creditors of William Jennings Allen, of Amen-corner, Paternoster-row, in the city of London, Wholesale Stationer, and of Combe Down, near Bath, in the county of Somerset, Paper-Maker (who died on the 23d of June 1839), are forthwith, by their Solicitors, to come in before Andrew Henry Lynch, Esq. one of the Masters of the said Court, at his chambers, in Southampton-buildings, Chancery-lane, London, and prove their debts, or in default thereof they will be excluded the benefit of the said Decree.[11] TO be sold, pursuant to an Order of the High Court of Chancery, made in a cause Poole versus Allen, with the approbation of Andrew Henry Lynch, Esq. one of the Masters of the said Court; Certain valuable leasehold estates, situate at Combe Down, near Bath, Somersetshire, and comprising that well known and beautiful estate, called the De Montalt Mills, with the cottages and land held therewith ; the tucking mill, with its cottage and stable, and the residence adjoining, called the Tucking Mill Cottage, with about four acres of land, by Mr. Thomas Mason, on Tuesday the 20th day of April 1841, at Garraway's Coffee-house, in the city of London, at twelve o'clock at noon, in three lots; Printed particulars may be had (gratis) at the said Master's chambers, Southampton-buildings, Chancery-lane, London; of Messrs. Walters and Reeve, Solicitors, No. 36, Basinghall-street; of Mr. Mares, Solicitor, No. 1, Vernonplace, Bloomsbury-square; of Mr. Croysdell, No. 33, Old' Jewry; and at the place of sale."[12]

Charles Middleton Kernot

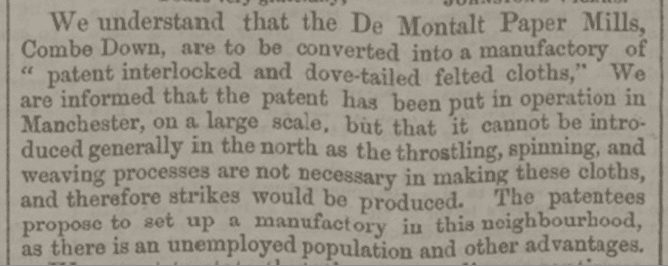

There were also a number of changes of use at De Montalt Mills. The Mill seems to have been unused in an industrial capacity since 1841 but on Thursday 13th July 1854 the Bath Chronicle announced it would reopen.

It was to be a ‘manufactory of patent interlocked and dovetailed felted cloths’! It was started by Charles Middleton Kernot (1807 – 1876) who seems to have been something of a character, and a polymath albeit a flawed one. He also appears to have been quite the inventor:

- in 1852 he had a patent for “improvements in the application of electricity and magnetism to the working of machinery and, and to telegraphic and manufacturing purposes”[7]

- in 1858 he had another patent for “improvements in distilling shale, boghead and other mineral matters”[8] in 1859 he had another for ‘paraffine’[9]

- in 1865 he published:

“Construction of railway plant to ensure the safety of passengers lives in the event of accident or collision. Being British Patent Number: 2463 published: 26 September 1865 Kernot, Charles Middleton & Simons, Nathaniel”.

But he also seems to have had his problems as did his family. In 1846 he had been involved in a Chancery case[10] which he lost and in 1848 he was made bankrupt.

As well as bankruptcy he also ended up in debtors prison for a while due to an action by his attorney in the Chancery case[11], Mr. Caitlin, for £547 18s 1d.

Mr. Caitlin got his debt law wrong and the case was non suited at which he brought an action against John Sturgess, a baker of Winchester, who was his assignee in bankruptcy.[12] He was discharged in 1850.

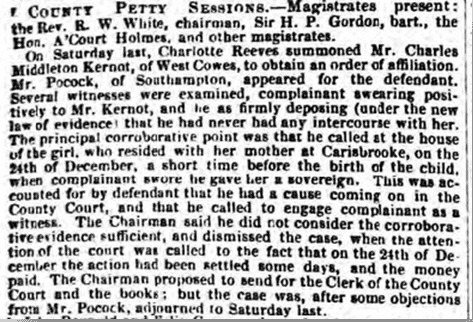

In July 1852 he was summoned by a Charlotte Reeves to obtain an order of affiliation. This is where a man judged to be the father of an illegitimate child has to contribute a specified periodic sum towards the child’s maintenance.

In 1852 his son Henry was arrested after he eloped with the servant girl having stolen £600 from his mother.[13] Quite what happened thereafter I have been unable to establish.

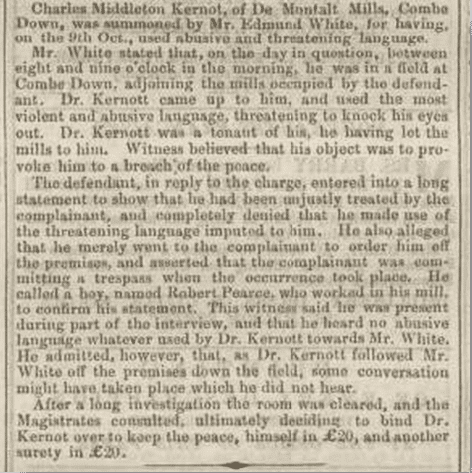

In 1856 Kernot was involved in an altercation with his landlord at De Montalt Mills, Edmund White, and was bound over to keep the peace.

The property was leased to Edmund White in 1849. White is listed as a linen and damask manufacturer and merchant in Bath, between 1836 and 1848 and additionally an undertaker from 1849. He was also noted as one of those from whom information regarding the services of the Bath Washing Company (see below) could be obtained.

In 1861 he was involved in another court case, which he also lost, about royalties for his paraffin invention.[14]

Under the General Pier and Harbour Act 1861, he and his son Charles Noyce Kernot received authorisation to build a pier and started the West Cowes Pier Company. The pier was 250 feet long with a 60-foot landing stage, a pagoda, a refreshment bar and a stage from which the Cowes Regatta could be watched. The pier was extremely popular, but on 28 September 1876 a tornado struck, destroying boats, houses, two seafront hotels and the pier.

In 1862 he was in court again: Charles Middleton Kernot, Esq., of West Cowes was charged by the Inspector of Nuisances under the Local Board, with having had in his possession a quantity of gunpowder above 50 lbs. in weight.

He not being a dealer or manufacturer of the gunpowder, under the provisions of the statute he had made himself liable to a penalty of 2s. for every pound so found on his premises over 50lbs., and the forfeiture of the said gunpowder.[15] In this case he was discharged as he proved that the gunpowder was not his but that he was holding it for a Mr. Robert Pinhorn. The gunpowder was returned and he received costs for the action.

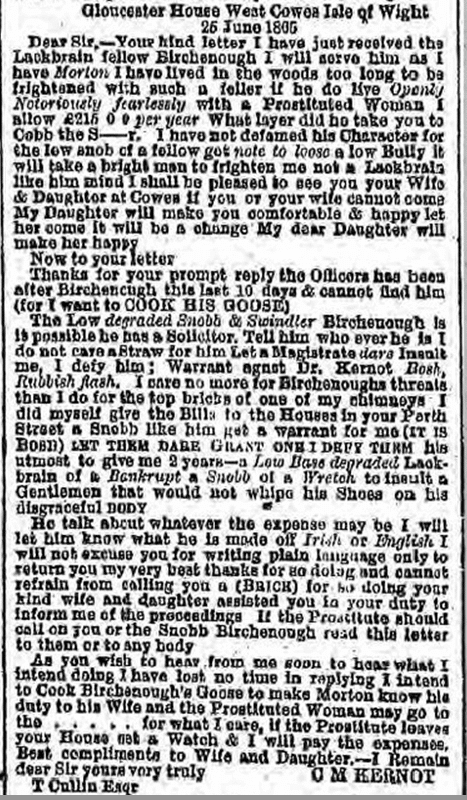

Charles Kernot’s (long suffering?) first wife Anne had died in 1859 and in 1864 he married Eliza Clark.[16] This was to lead to him appearing in court yet again and to be imprisoned for 1 month in Lancaster for “maliciously publishing false and defamatory libel knowing the same to be false”.

His wife had let some rooms in Everton from a Mr. Birchenough. Charles Kernot suspected something and printed up some bills (I have been unable to find out exactly what was in them, but they mentioned Mrs. Kernot, Mr. Birchenough and allegations similar to the one in the letter produced for the trial and printed in the Liverpool Mercury). In essence Kernot accused his wife of living with Birchenough and said that Birchenough was a bully. He was found to have libelled Birchenough and sent to prison. Unsurprisingly his wife petitioned for divorce. Charles Middleton Kernot was quite a character and although he never lived on Combe Down his association with it is really quite interesting.

After Charles Middleton Kernot

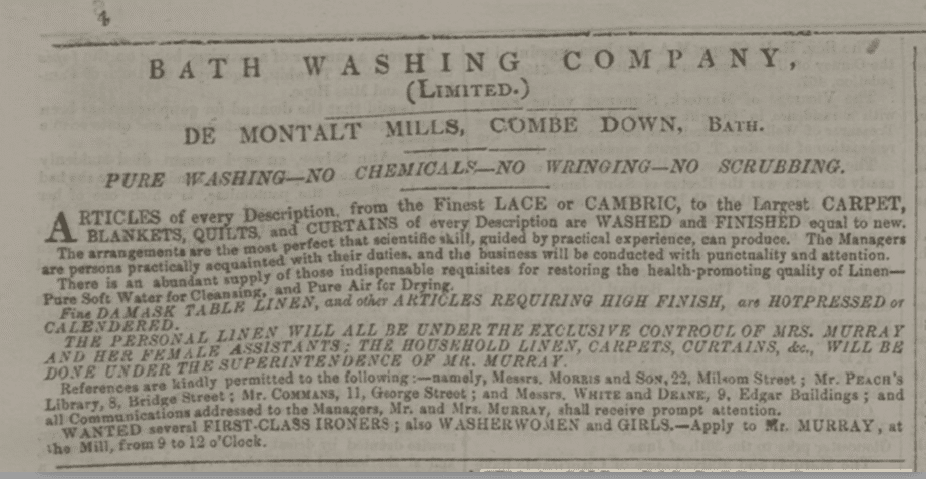

In 1859, after Charles Kernot’s venture had foundered, De Montalt Mill became a laundry run by the Bath Washing Company Ltd. There is a lovely description of what they do and how they do it in Bath Chronicle of Thursday 3rd November 1859. The Bath Washing Company also advertised quite heavily in the Bath Chronicle but by 1864 it had moved to new premises at Twerton.

In 1861 a part of the premises were occupied by John Cooksley, gardener.

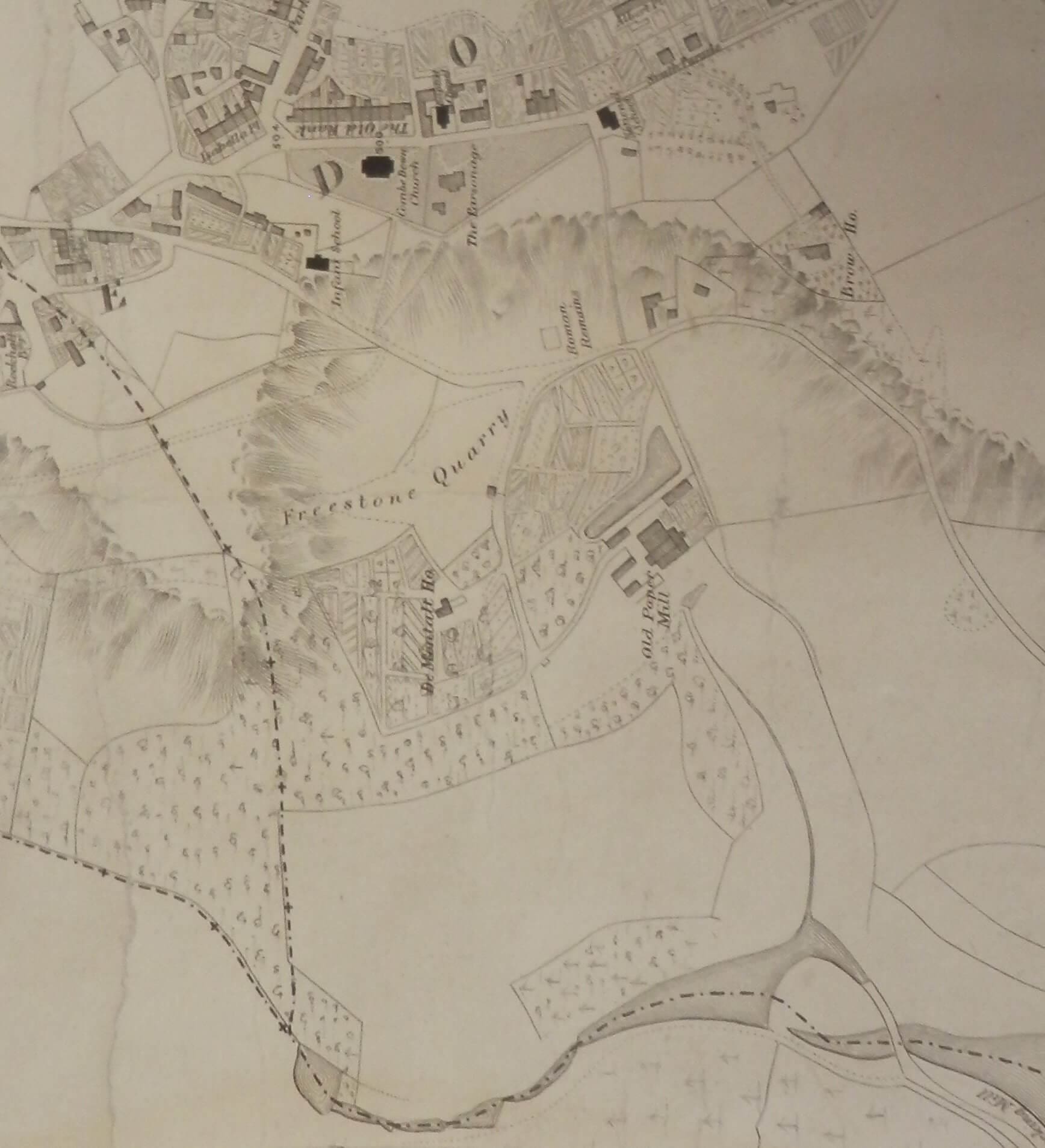

Cotterell’s map of 1852 shows the area north of the mill pond as market gardening.

By 1864 the mill is listed as being occupied by Edward Ashley, market gardener who remained at the premises until 1869.

In 1869 the property is once again advertised for sale as being ‘suitable for a variety of manufactures: Brewery, corn mill, cloth factory, or any other trade requiring water-power’. This suggests that the wheel was still present and functioning at this time.

The Bath Board of Guardians, who were responsible for administering Poor Law from 1835 to 1930, considered buying De Montalt Mills for use as a separate school but it was felt to be too expensive a scheme[17].

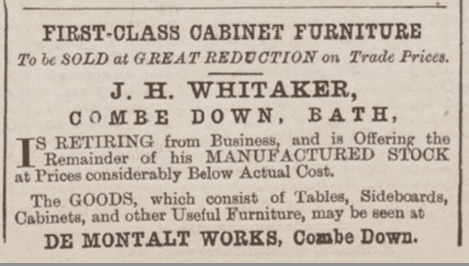

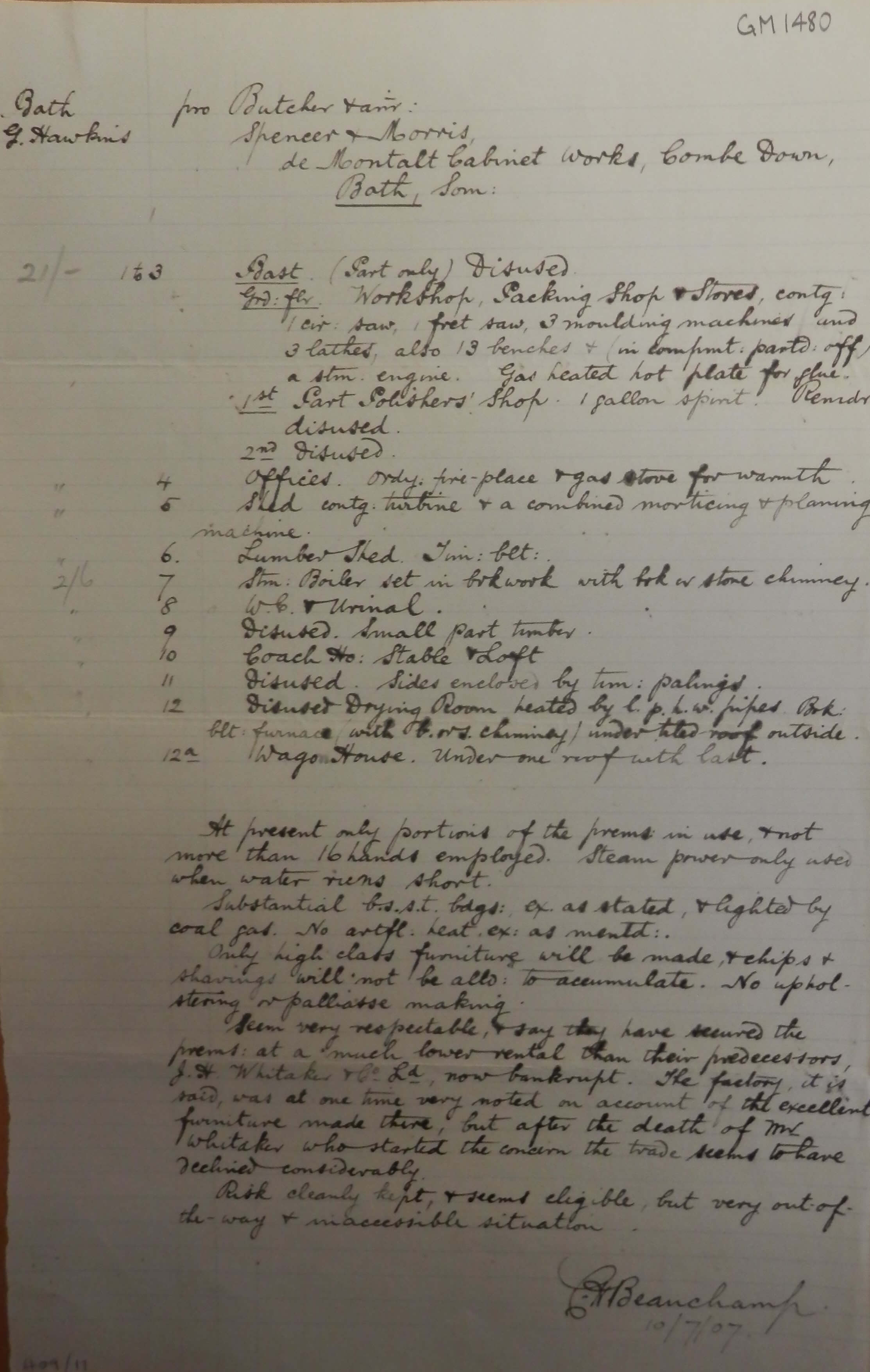

In about 1875 John Hector Whitaker (1821 – 1899), a cabinet maker, moved his business to De Montalt mills and was by 1881 employing “45 men, 18 boys and 3 girls”. He retired in 1894/1895 and the business continued with a William Clapp listed as secretary and manager between 1900 and 1907 when the firm went bankrupt.

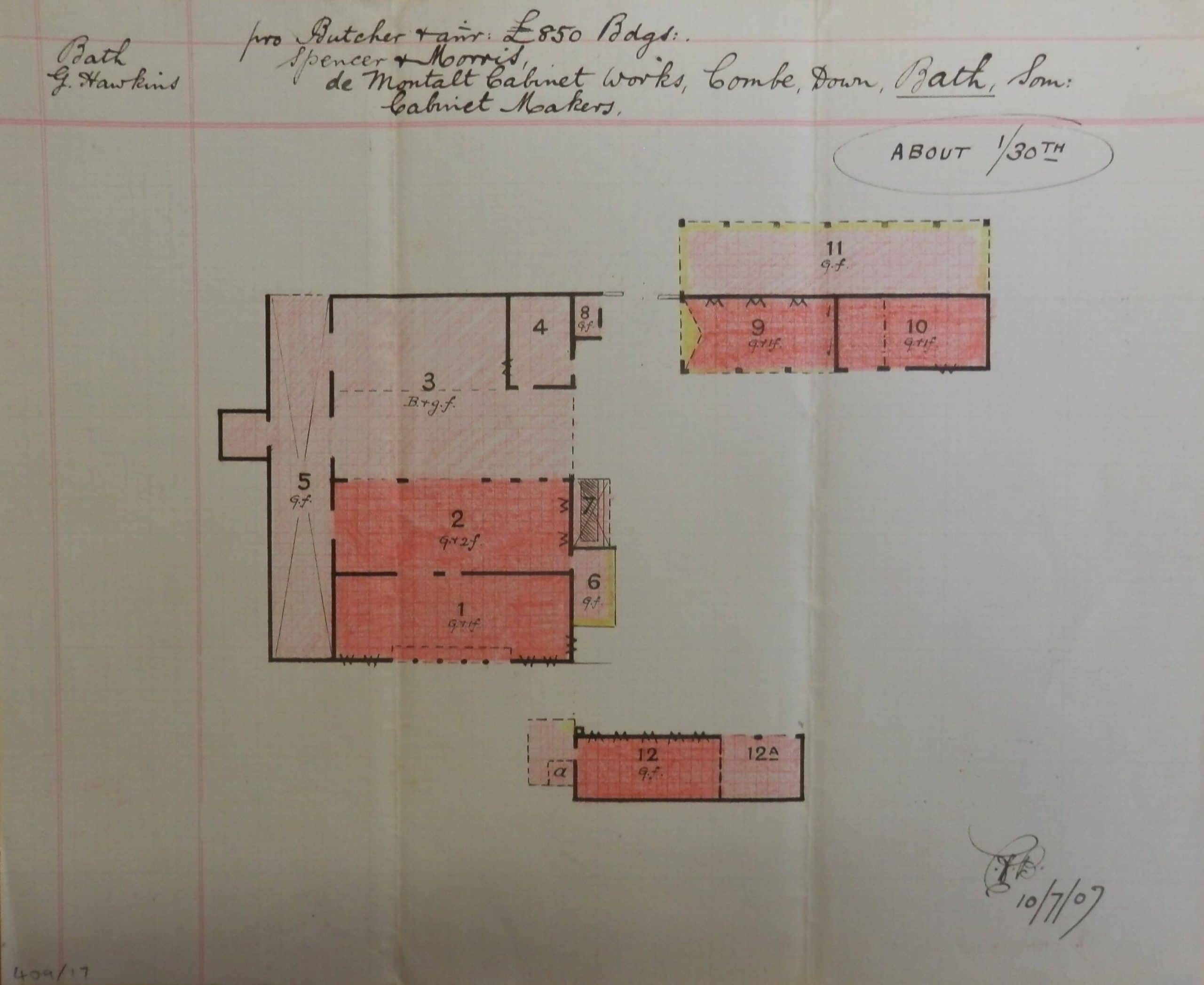

They were succeeded by Spencer & Morris as the insurance report and layout below from 1907 shows, but I have been unable to establish how long they lasted.

In 1921 after standing empty for some time the mill and land were purchased by a Mr Mann for use as a farm. It remained in this use until 1987 but had become derelict. In 2006 it was redeveloped as housing.

Jewish Cemetery

Jewish Burial Ground

The first written record of Jewish settlement in England dates from 1070. The Jewish presence continued until King Edward I‘s Edict of Expulsion in 1290. After the expulsion, there was no Jewish community, apart from individuals who practised Judaism secretly, until the rule of Oliver Cromwell.

While Cromwell never officially readmitted Jews to Britain, a small colony of Sephardic Jews were living in London in 1656 and allowed to remain in exchange for finance.

The Jewish Naturalisation Act 1753, was an attempt to legalise the Jewish presence in England, as during the Jacobite rising of 1745, the Jews had shown particular loyalty to the government. remained in force for only a few months.

The public reacted with an enormous outburst of antisemitism, and the Bill was repealed in the next sitting of Parliament, in 1754.

Jewish emancipation came between 1829 and 1858 when Jews were finally allowed to sit in Parliament, though Benjamin Disraeli, born Jewish though baptised aged 12 into the Church of England, had been a Member of Parliament from 1837.

At the insistence of Irish leader Daniel O’Connell, in 1846 the British law “De Judaismo” was repealed.

Jews visited Bath from the 1730s, coming to take the waters.

The first identifiable Jewish visitor, Catharine da Costa, was with her children at the Bath, recovering her strength, in 1731. Eight years earlier Mr. Dias, Marcus Moses and Joseph Musaphia appear in the first list of subscribers to the Bath General Hospital.[2] The second list, opened in 1737, includes Messrs. Salvador, Capadose, Moses Pereira and Mrs. Pereira, and Aaron Franks.[3]

A Jewish community started to form from the 1740s as doctors dentists, optometrists, chiropodists, greengrocers, jewellers, tailors and second-hand clothiers arrived to serve their community. The community was never a large one, consisting of only fifty people in 1845.[4] They also had to perform other tasks required for religious observance such as schochet (slaughterer) and mohel (circumciser).

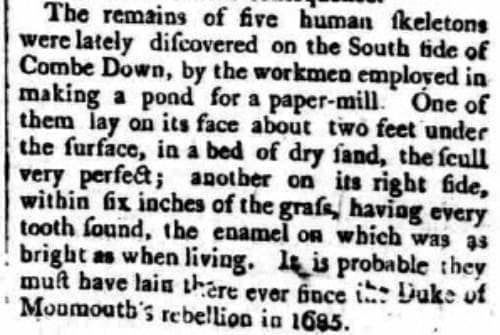

The Jewish Cemetery land, near Greendown Place on Bradford Road, was purchased in 1812 from Henry Street (1776 – 1858), who had a quarry there, though it is also said that it was founded in 1815 and its title deed dates from 1820. It was enlarged in 1862.

There is some confusion about the first burial. The International Jewish Cemetery Project suggests Sarah Moses in November 1812 whereas Cemetery Scribes suggest Aharon b Moshe (1779 – 1826) in 1826. The Friends of Bath Jewish Burial Ground say the earliest gravestone date is 1842. The cemetery is one of only fifteen Jewish cemeteries surviving from the Georgian period in the country.

The last interment is said to have been that of Reuben Somers in 1942 but the latest gravestone is dated 1921 indicating that there are some unmarked graves. There are about fifty gravestones and five chest tombs.

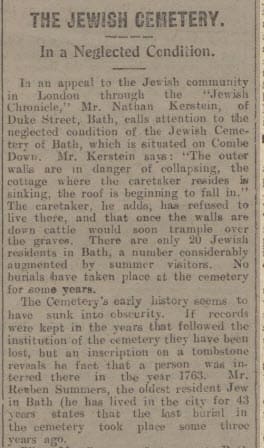

The burial ground had been neglected for many years and no ownership has been established because the original trustees died early in the 20th Century. However, the Board of Deputies of British Jews has accepted responsibility for it.

The Friends of Bath Jewish Burial Ground was set up in 2005 by the Combe Down Heritage Society and the Bath Jewish Community. It aims to restore the site for public access and as an educational resource. Local members, working with the Jewish community and the Board of Deputies of British Jews, have made a start on clearing undergrowth, repairing the wall & surveying the site.

More recently The Friends of Bath Jewish Burial Ground have carried out more extensive research which shows that the cottage at the burial ground had a Jewish religious function. They have clearly established that this is not the case and that the building was a cottage for local workers and their families until its partial demolition in 1929.

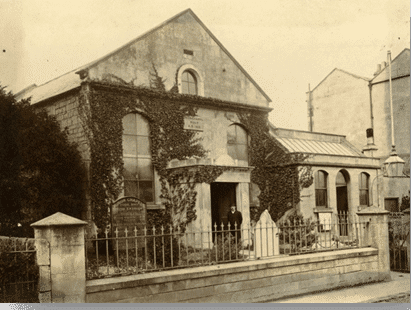

A synagogue, Bath Hebrew Congregation (Ashkenazi Orthodox) was created at at 19 Kingsmead Street (now James Street West and Monmouth Street) about 1815. The synagogue lay due west of Abbey Square. The building had formerly been the New Theatre and then a girls’ school.

By 1841 there was a purpose-built synagogue, Bath Old Synagogue in Corn Street, the cost for which was provided in the will of Moses Samuel (d.1839), who lived at 42 St James Square. He had founded the earlier synagogue in Kingsmead Street.

Regular services ceased in about 1874 and the synagogue fell into a state of disrepair. Attempts were made to raise funds to restore the building and the synagogue was reactivated by 1880, with the assistance of ‘minyan men‘ from Bristol. However, it fell on hard-times again and by 1881 was largely defunct.

In 1894, the synagogue was badly damaged in flood and by 1903, has fallen completely out of use. In 1911, the lease expired and the building, now derelict, was taken over by St Paul’s Church, before being compulsory purchased by the local authority in 1938 as part of the Technical College development.

Bath Hebrew Congregation was re-established in the 1920’s[5] and services were held at Kerstein’s Private Hotel, 10 Duke Street, Bath, Somerset.[6]

From “The Jews of Bath” by Malcolm Brown and Judith Samuels 1988

Headstones at the Jewish Cemetery, Combe Down – there are 51 gravestones of which only these are now legible

| Name | Age | Gregorian date | Jewish date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel Rees (of 20 Bathwick Street) | 84 | 21 Jan 1842 | 10 Sh’vat 5602 |

| Abraham Rees (of 20 Bathwick Street) | 85 | 17 Jan1845 | 9 Sh’vat 5605 |

| Myer Fishel | 83 | 5 Oct 1861 | 1 Cheshvan 5622 |

| George Braham | 55 | 21 Dec 1865 | 3 Tevet 5626 |

| Samuel Jacobes (of 12 Bladud 13uildings) | 64 | 2 Feb 1866 | 17 Sh’vat 5626 |

| Rev. Solomon Wolfe (Reader to the Congregation for fifty years) | 87 | 17 Jan 1866 | 2 Adar 5626 |

| Matilda Samuel | 65 | 8 Jan 1867 | 2 Sh’vat 5627 |

| Phoebe Jacobs (widow of Samuel Jacobs) | 69 | 19 Feb 1867 | 14 Adar 5627 |

| Jesse Fishel | 74 | 13 Jan 1870 | 29 Sh’vat 5630 |

| Morris Abrahams | 77 | 27 Jul 1877 | 17 Av 5637 |

| Maria Michaels | 78 | 5 Oct 1878 | 8 Tishrei 5639 |

| Lh Brooks (wife of Alfred Brooks) | 31 | 30 Aug 1883 | 27 Av 5643 |

| Herentz Leon (of 1 Claverton Buildings) | 78 | 10 Dec 1884 | 22 Kislev 5645 |

| Harriet Jacobs (daughter of Samuel and Phoebe) | 63 | 22 Dec 1885 | 19 Tevet 5646 |

| Rachel Jacobs (daughter of Samuel and Phoebe) | 62 | 15 Jan 1888 | 2 Sh’vat 5648 |

| Harry Cohen | 14 | 5 Mar 1889 | 2 Adar II 5649 |

| Aaron Morris | 48 | 18 Dec 1889 | 25 Kislev 5650 |

| Rev. Nathan Jacobs | 64 | 12 May 1890 | 22 Iyyar 5650 |

| Hyman Somers (son of Reuben Somers – born 25 Dec 1877) | 15 | 7 Mar 1905 | |

| Henriette Leon (of Lime Lodge, Oldfield Park – born Hildesheim on 26 Jul 1823 (5583)) | 71 | 22 Sep 1894 | 21 Elul 5654 |

| Eveline Sloman (daughter of Leman and Elizabeth Levi of London) | 47 | 1 Apr 1896 | 18 Nisan 5656 |

| Julia Jacobs (daughter of Samuel and Phoebe) | 71 | 13 Jan 1897 | 10 Sh’vat 5657 |

| Abraham Leon (of Lime Lodge, Oldfield Park – born Hagenow on 28 Aug 1818) | 23 Aug 1897 | 25 Av 5657 | |

| Minnie Tyler (daughter of Simon and Freda Tyler) | 2 | 28 Mar 1898 | 2 Nisan 5658 |

| Hannah Jacobs (widow of Nathan Jacobs) | 75 | 10 Mar 1899 | 28 Adar 5659 |

| B, Barnett | 68 | 14 Apr 1901 | 25 Nisan 5661 |

| Kate Aaron (wife of Samuel Aaron) | 75 | 9 Oct 1901 | 26 Tishrei 5662 |

| Joseph Jacobson (husband of Antonia) | 73 | 11 Feb 1920 | 22 Sh’vat 5680 |

| Solomon Kesseff | 6 Dec 1921 | 5 Kislev 5682 | |

| Undated | |||

| Joseph Sigmo (nd) | |||

| Frances Ulman (Pious Priestess) | |||

| Lewis Cohn Silverstone (born December 1851 died 23 January ?) | |||

| Elizabeth Simmons (22 November ?) |

N. B. You can find out more about the Jewish Burial ground here.

Union Chapel

Union Chapel

Prior to the Union Chapel the only place of worship on Combe Down was a room in Dial House, but a growing population of stone quarrymen meant a proper building was needed.

Many of the stone quarrymen were dissenters (or non-conformists) and had religious and political views that were different from the establishment. This created some difficulties with the authorities.

Union Chapel is a dissenting or non-conformist church and was founded by members of two churches in Bath Argyle Street Congregational Church & Somerset Street Baptist Chapel.

The land was bought in 1814. The deed is signed by William Jay of Argyle Street & Rev. John Paul Porter of Somerset Street.

Union Chapel was opened in 1815. It was altered in 1909 when the upper floor was added to the school room to provide five extra classrooms and in 1957 when the hall to the left of the entrance was built to provide more space for children.

Having re-established the monarchy in 1660, parliament passed a range of legislation to suppress dissenters:

- Corporation Act 1661, repealed 1828, to stop office holding by dissenters.

- Act of Uniformity 1662 to hold any office in government or church & prescribed the form of public prayer.

- Conventicle Acts 1664, 1669, repealed 1812, no more than five people except the household to ‘be present at any Assembly, Conventicle, or Meeting’ for religious worship other than CofE.

- Five Mile Act 1665, repealed 1812, ministers not allowed within five miles of any corporation that returned MPs or parish where they had been minister or preached.

- Test Acts 1673, 1678, repealed 1828, required anyone in office take the Oath of Supremacy & receive the sacrament communion from the Church of England. Penalties were severe. Offenders risked a £40 fine or six months’ imprisonment.

- The Act of Toleration 1689, allowed nonconformists their own places of worship, teachers & preachers subject to pledging the oaths of Allegiance and Supremacy & rejecting transubstantiation. However, dissenters were forced to pay local rates for parish churches until 1868 & excluded from Oxford & Cambridge universities until 1871.

N. B. You can find out more about who is buried at Union Chapel at the BRO Union Chapel burial page.

Monkton Combe Brewery

Monkton Combe Brewery

Large human settlements could develop only where fresh surface water was plentiful, such as near rivers, but far more often close to natural springs. For millennia this, generally, was fine but with industrialisation sewage and factories released more contaminants and pollutants into rivers, streams and groundwater.

Small beer from the second or perhaps third mash of a brew, which was mildly alcoholic (0.5 – 2%) and bitter, had provided a safe drink for centuries. Beer production using hops and the conversion of malt into fermentable sugars requires soaking and sparging in water which has been heated to and kept at approximately 150 degrees fahrenheit. This pasteurises the wort and is together with an acidic pH makes small beer safer than many water supplies in larger towns and villages whilst still being thirst quenching.

Of course ordinary beer was also enjoyed as an alcoholic drink by many too!

Brewing originated as an everyday domestic activity and in the medieval era monasteries were the large scale brewers but by the 16th century the dedicated brewhouse was becoming commonplace. In the provinces, large commercial breweries began to appear from the 1780s. Monkton Combe brewery may have existed from about this time – certainly a maltster called John Ward died at around the end of 1781.

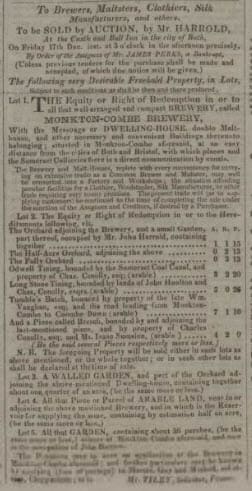

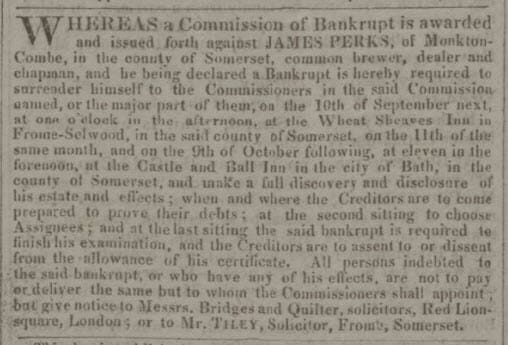

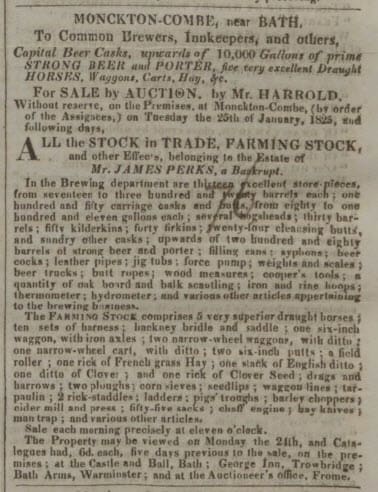

Charles Perks (1749 – 1813) was entrepreneurial being a bacon merchant and involved in the break up of the De Montalt estate. It may be that he took over this business. Certainly his son James Carpenter Perks (1785 – 1866) owned Monkton Combe brewery by this time. Unfortunately, by September 1824 he was made bankrupt and the brewery was put up for sale.

Quite what happened then is unclear, but in 1831 the brewery is up for sale again.

This time it is his half brother Robert Holway Perks (1775 – 1831) that is the bankrupt and owner of Monkton Combe brewery, so it may be that he bought it out of bankruptcy?

The process went on a long time as adverts for creditors were still being placed in Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette on Thursday 8 March 1838 and the Viaduct pub – which seems to have been owned by the brewery – was not advertised until 1840.

Thereafter I have been unable to discover any more, so, presumably, whilst the Viaduct went on to open a brewhouse later in the century, Monkton Combe brewery no longer traded.

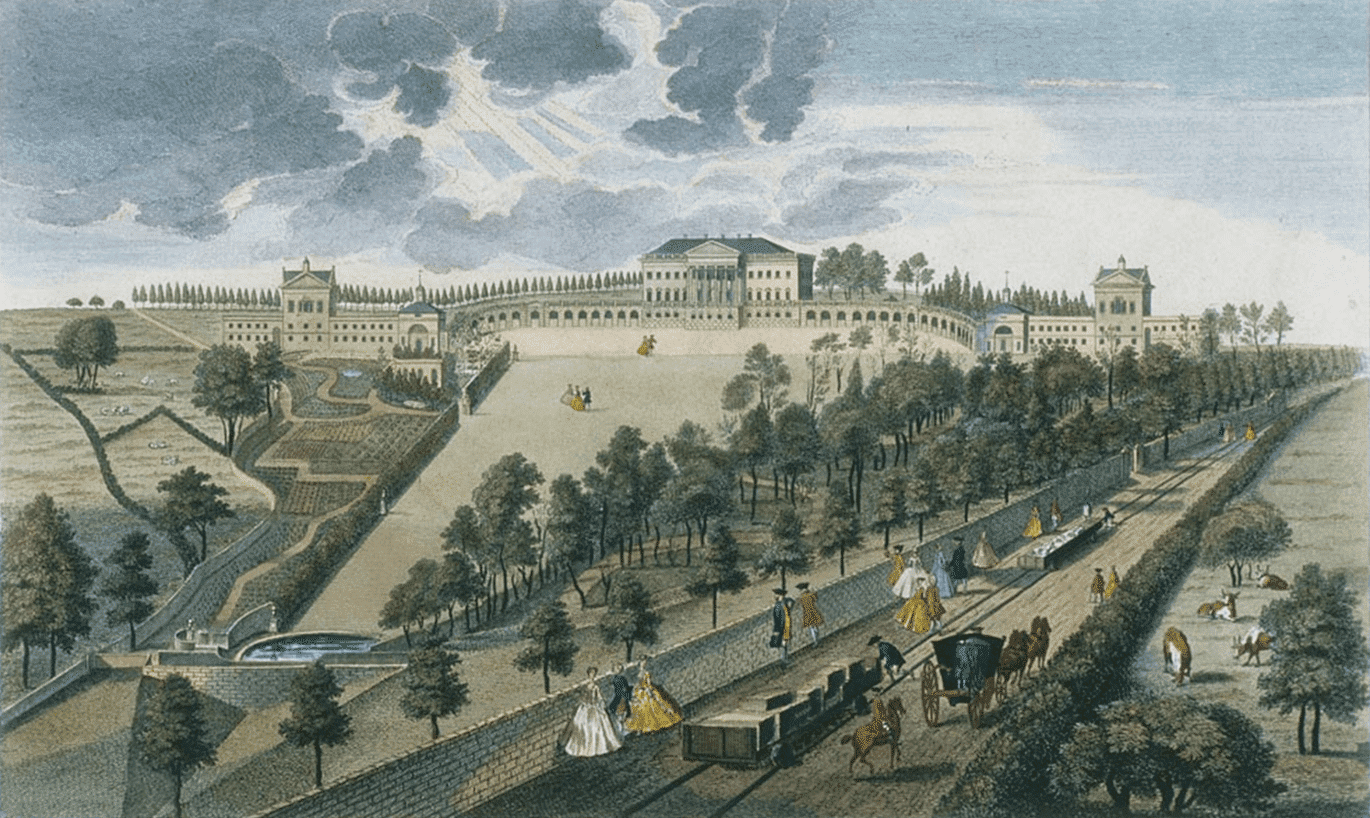

Opening Carriage Drive

After he completed his purchases of stone quarries on Combe Down and before he built Prior Park, Ralph Allen built a tramway, in about 1730, to carry his stone from Combe Down to Dolemeads. This, later, became the private driveway to Prior Park, the tramway being removed soon after his death in 1764.

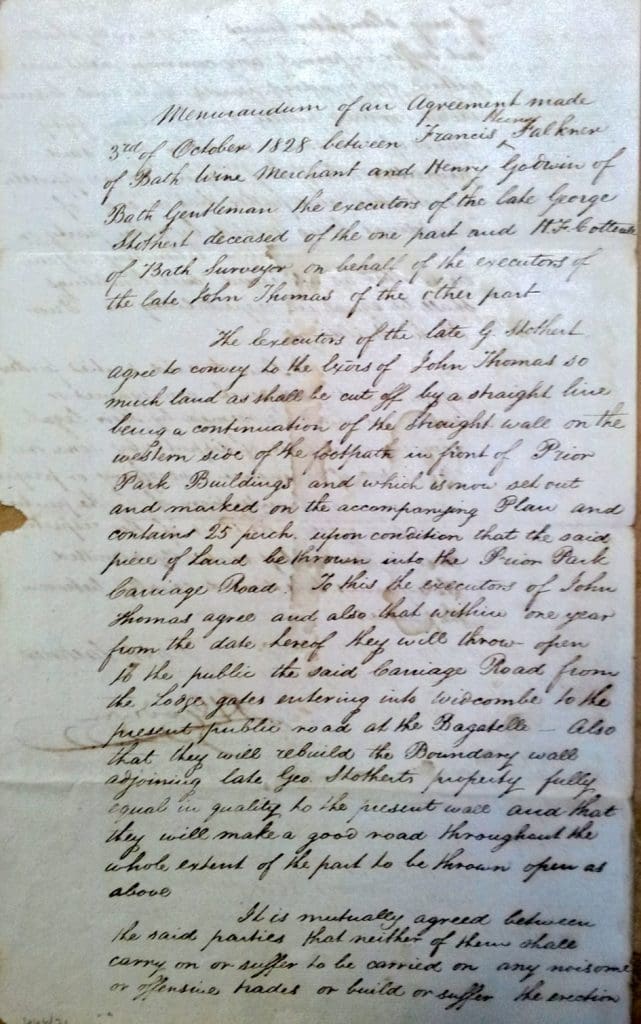

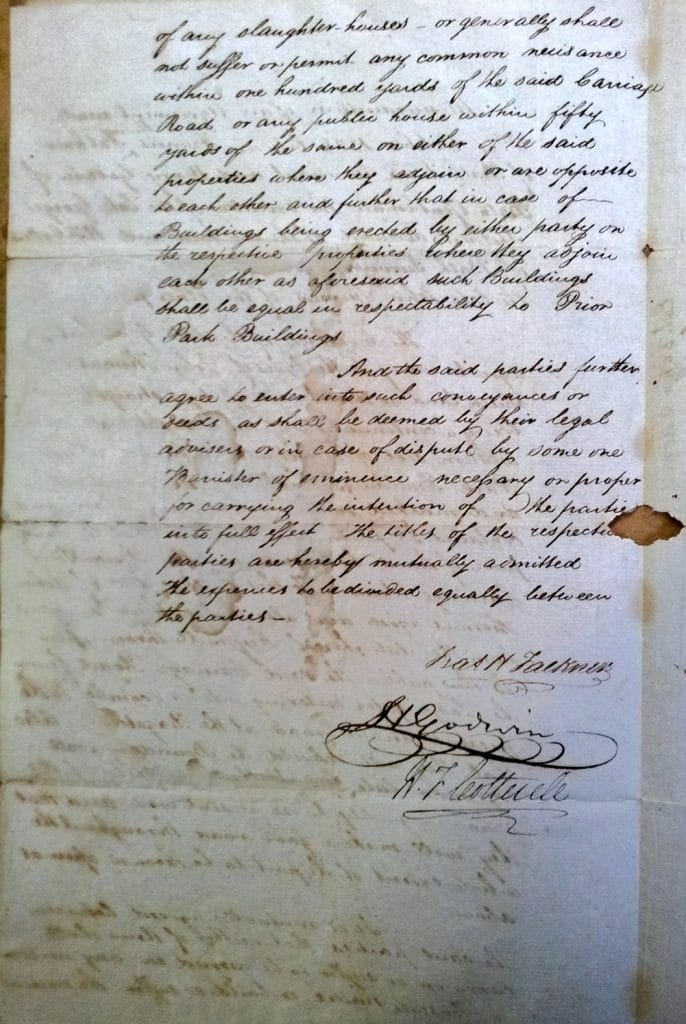

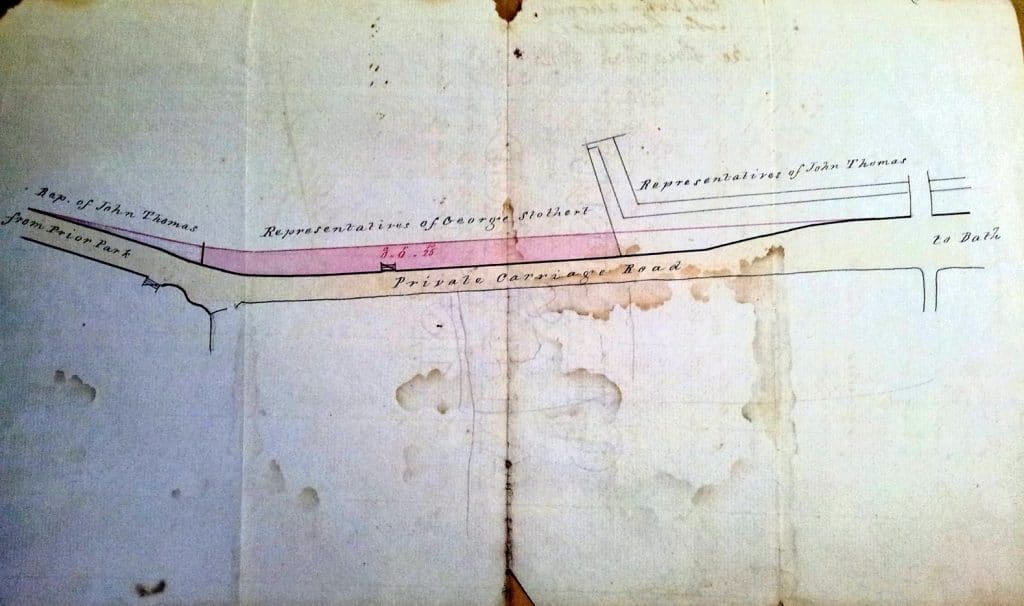

About 100 years after it was built the executors of John Thomas (1752-1827), who had bought Prior Park and George Stothert (1755-1818), who owned land in Widcombe came to an understanding to widen Carriage Drive and open it to the public.

This may have been decided so that the further development of Combe Down was made easier and the increased access to the village made developments more attractive.

In the memorandum we find some names that have already appeared in this work.

Francis Henry Falkner (1786-1866) was an Alderman of Bath and brother to Richard Falkner (1796-1863). His daughter was Sarah Stringer Falkner (1820 – 1910) whose granddaughter was Lilias Mary Campbell (1865 – 1940), the first wife of Gen Edgar Montagu Pilcher DSO CB CBE (1865 – 1947) who lived at Ashlands.

Their mother was Catherine Parsons (1753-1840) whose sister Sarah Parsons (b 1745) married John Asprey (1746-1801) who were the parents of Elizabeth Asprey (1765-1855) who married George Stothert (1755-1818) father of Henry Asprey Stothert (1797-1860), founder of Stothert and Pitt.

Henry Fowler Cotterell (1791 – 1860) was second cousin to John Ovens Thomas (1778 – 1836), the son of John Thomas (1752-1827); he was also grandfather to Thomas Sturge Cotterell (1865 – 1950) who built Lodge Style and was a Mayor of Bath.

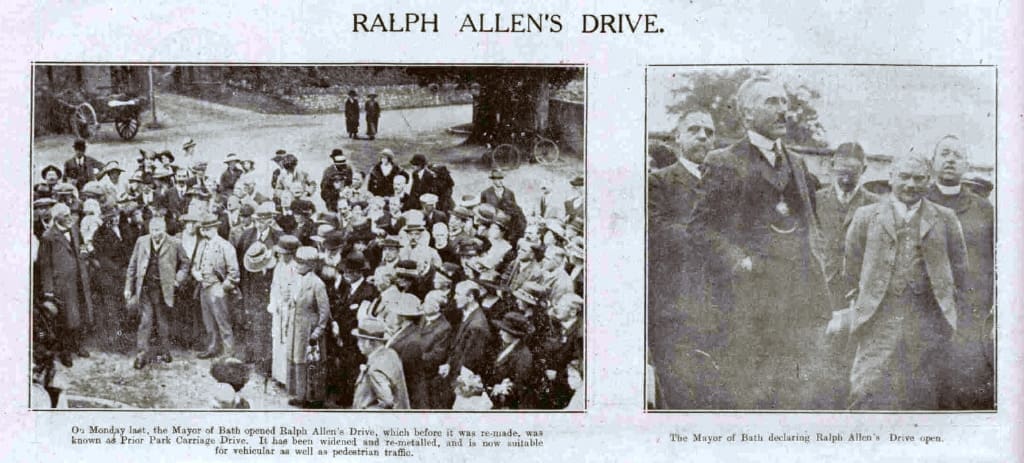

We can see, form the clippings below, that it took some time more to open the road to the public than had been initially anticipated, but that by 1834 Carriage Drive had become a public road.

About 90 years later came the next stage, the decision to widen Carriage Drive and rename it to Ralph Allen Drive.

School

Bath District National School

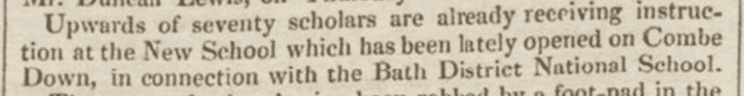

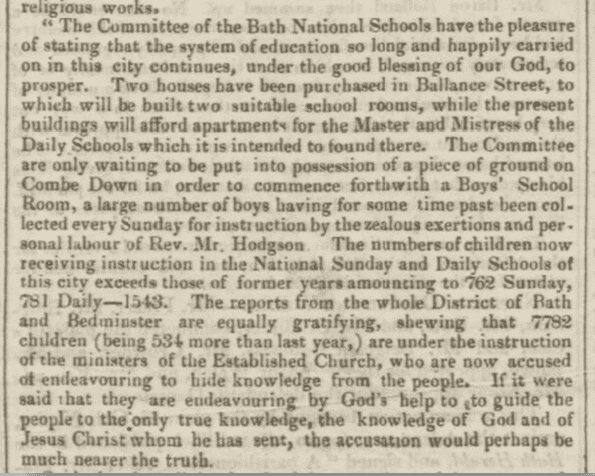

By November 1830 a National School Society school had been opened on Combe Down built with a donation by Thomas Tanner (1771 – 1846). This is the old school house on the corner of Church Road and Belmont. The West front range, was the school master’s house on the ground and first floors with the school room above on the second floor. In 1887 a large single storey schoolroom wing was built at the back (East) and c. 1900 a further school room was built on the South side of the rear wing.

Charity Sunday schools had been established in Bath in 1785 and by 1816 had led to the establishment of a ‘District National School’ at Weymouth House in St. James’s Street.

The District National Schools were set up on ‘the plan of Dr. Bell’. Andrew Bell was a Scottish minister who had worked in Virginia, America as a private tutor for 7 years and in Madras, India for 10 years.

His ‘Madras System’ was based on the abler pupils being used as ‘helpers’ to the teacher, passing on the information they had learned to other students. He said that whilst in India he had seen some Malabar children teaching others the alphabet by drawing in the sand and decided to develop a similar method, putting older children in charge of younger. Essentially, a schoolmaster would teach a group of older students some basic lessons and they would then relate the lesson to a younger group of children. It was a cheap way of managing primary education as it allowed larger class sizes, something that was essential at the time.

By 1836 the number of children to be educated, coming from Combe Down, Monkton Combe and Southstoke was such that further school premises were found and by 1840 would be in use.

This was the school on the corner of Belmont and Summer Lane and the girls moved here whilst boys continued to be educated at the original building on the corner of Church Road and Belmont. This building was also built with a donation from Thomas Tanner.

By 1855 the structure changed again with the older girls and boys recombining to go to the original school building on Church Road as Combe Down Church of England Elementary School (or the Upper School) and the younger children staying in the building on Summer Lane as Combe Down Infant’s School.

It should be remembered that until 1870 there was no compulsory education. The Elementary Education Act 1870 compelled local authorities to provide elementary education for children aged 5 – 13, although didn’t insist on compulsory attendance.

The Elementary Education Act 1880 insisted on compulsory attendance from 5–10 years. The Elementary Education (School Attendance) Act 1893 raised the minimum leaving age to 11 and was amended in 1899 to raise the school leaving age up to 12.

The Education Act 1918 enforced compulsory education from 5 – 14 years and compulsory part-time education for all 14 – 18. The Education Act 1944 raising the school leaving age to 15. It was not until 1972 that school leaving age was raised to 16.

When Ralph Allen school opened in 1958 the pupils between 11 and 15 moved there and the building on Church Road became Combe Down Junior School.

In 1990 the ‘log cabin’ school was built and the junior and infant schools merged to become Combe Down Church of England Primary School.

The old school house was sold and converted into housing and the old playground in the long drung was also built on.

Church

Holy Trinity Church

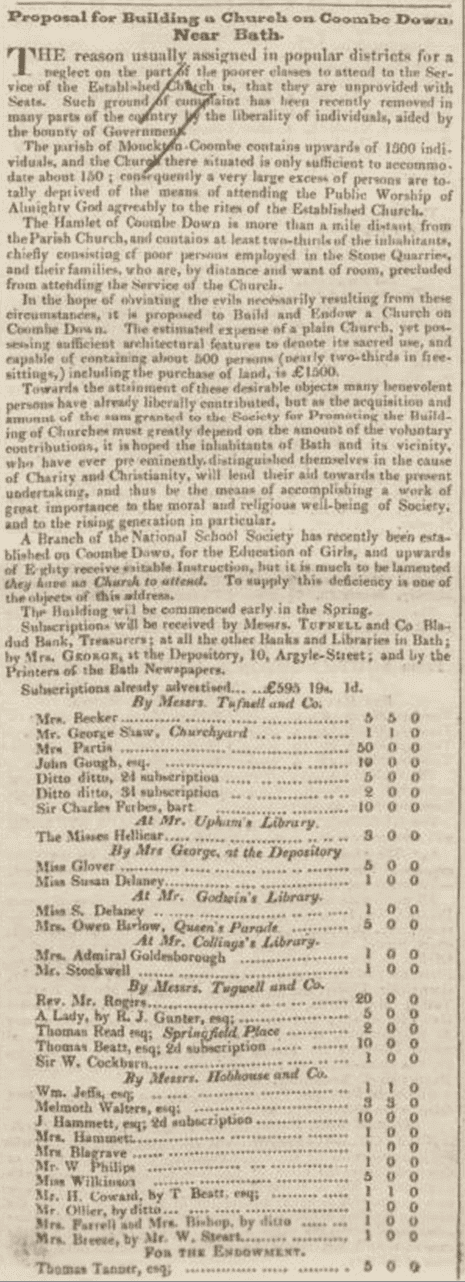

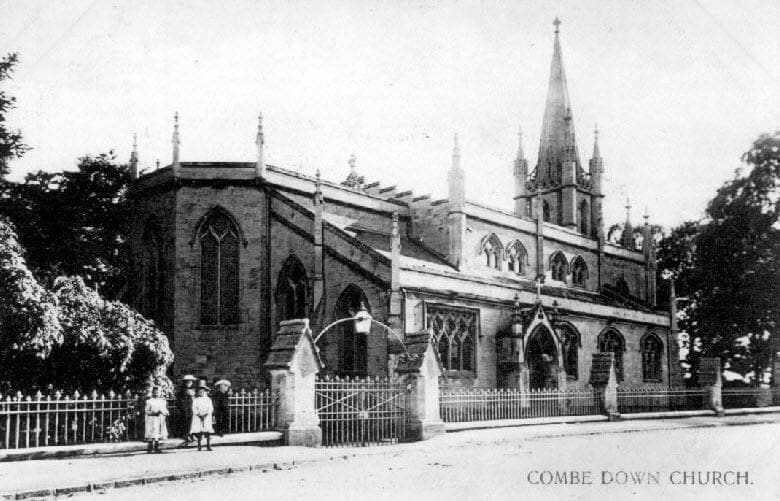

By 1831 there were enough residents for there to be a feeling that a church was needed for Combe Down.

The land was purchased in December 1831 and the foundation stone laid in May 1832[7].

A request for tenders was put out in Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette on Thursday 26 April 1832 and the building proceeded with further gifts from Mrs. Partis.[8]

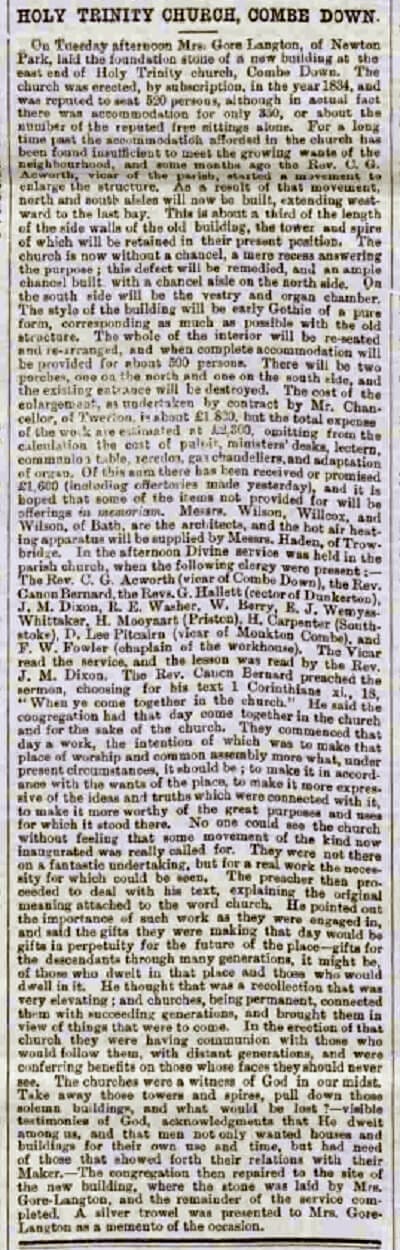

Holy Trinity church was consecrated on 29th June 1835 though it was not until 50 years later that side aisles were added.

Of course one thing was missing and that was somewhere for the minister to live and so an appeal was launched in 1836 in The Bath Chronicle. It seems £400 had already been collected for ‘the erection of a Parsonage House’.

There was enough confidence to start calling for tenders as an advert from the Bath Chronicle, Thursday 27 April 1837 shows.

Building the Parsonage did not all go smoothly as the foundations proved a problem due to the previous quarrying on the site. It seems the builder would not agree to cover the cost of foundations within the specification and an extra £330 had to be raised in 1841 to ensure that the outstanding debt for the building could be paid off.

On Thursday 2nd July 1840 there is another advert in The Bath Chronicle which states that Claremont House is up for auction again. It is not clear who bought it. A few years later on Thursday 29th April 1847 there is another advert to sell it by auction again. It is not clear who bought it this time though it may have been Edward Palethorpe.

In the same edition, of Thursday 2nd July 1840, is also a notice that the Carriage Inn and also the land opposite is for sale – with a lovely description.

Holy Trinity Church extension

On 7th August 1883 Mrs. Gore Langton of Newton Park laid the foundation stone for an extension to Holy Trinity of North and South aisles, a chancel, vestry and organ chamber. £1,600 of an estimated £2,300 cost had been raised.[65]

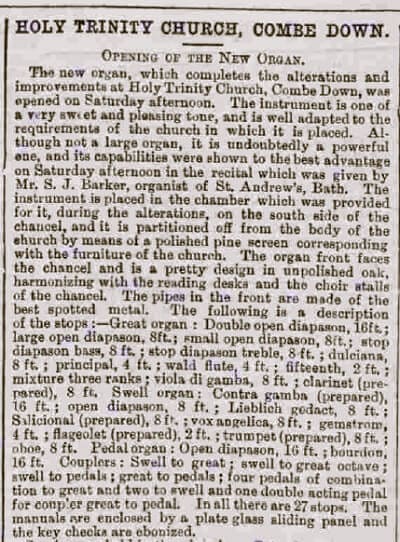

The new extensions were consecrated on Thursday April 3rd 1884[66] and on 19th July 1884 the new organ was opened.[67]

Workhouse

Frome Road Workhouse

Although it is, strictly, on Odd Down, it is worth mentioning the Frome Road Workhouse, later St. Martin’s Hospital.

Prior to the passing of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, the administration and finance of poor relief and workhouses was, for the most part, organized at the parish level — a situation which had been laid out by the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1597 which was amended by the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601.

Administration of the 1601 Act was conducted by ‘the Vestry‘ which was the governing body of a parish and included the minister, the churchwardens and respected householders.

Assessment and collection of the poor-rates was carried out by 2 – 4 unpaid parish overseers in each parish. They were appointed annually, with the approval of the local Justices of the Peace. Churchwardens could act as ex-officio overseers.

Poor relief was an onerous task for a parish and sometimes ‘farmed’ by a contractor who would house and feed the paupers for a fee and often be allowed the income from work performed by the paupers.

Because of the poor law a number of civic incorporations began to be formed through parliamentary local acts staring with Bristol in 1696. These were usually run by elected boards of guardians and had paid officers. Gilbert’s Act of 1782 allowed groups of parishes to form unions managed by elected guardians. William Sturges Bourne’s Acts of 1818 and 1819 provided for the setting up of ‘select vestries’ with elected members and salaried assistant overseers.

In 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed based on the recommendations of a Royal Commission.

It started an administrative revolution with a central commission with powers to establish efficient local administrations and supervise the work of locally elected guardians. The system was based on a new administrative area called the Poor Law Union, each of which was required to operate a Union workhouse as the principal channel for providing relief.

The table gives an idea of how it worked based on The New Poor Law Amendment Act, With A Practical Introduction, Notes, And Forms. By John Frederick Archbold, Esq. Barrister At Law, 1842.

| Poor Law Commissioners (1834-47); Poor Law Board (1847-71); Local Government Board (1871-1919) Ministry (now Department) of Health (1919-) |

Responsible for government policy on health |

| Poor Law Union Board of Guardians | Administered workhouses within a defined poor law union consisting of a group of parishes with a:

|

| Workhouse | The place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment and had:

|

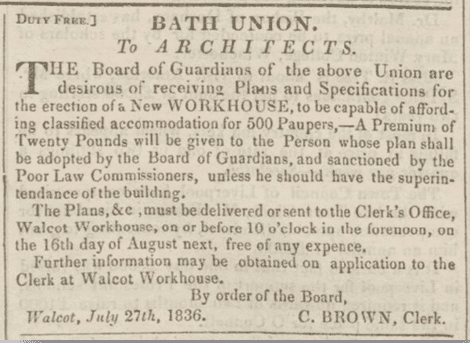

So on 28th March 1836 the Bath Poor Law Union was formed with 41 guardians representing 24 constituent parishes including Monkton Combe.

By June 1836 it had been determined that a new workhouse was required as it would cost at least £10,000 to upgrade the existing buildings and, even then, they would be inadequate.[13]

By the end of July advertisements for tenders had been placed.

It was constructed from 1837 on 5 acres of land bought for £530 and the original buildings cost £11,800. In 1842 another 5 acres were purchased and it was enlarged. In 1855 11 more acres were added and it was enlarged again, as it was in 1865 when another 3 acres were bought. In all, it cost £21,750 with £18,870 for buildings and £2,700 for land. The original capacity was 500 and by 1865 1,029 people were there.[14]

It was built by Sampson Kempthorne (1809 – 1873) who emigrated to New Zealand in 1842. He specialised in the design of workhouses to two main designs, the square plan and the hexagonal or “Y” plan, and built twelve new workhouses in nine counties in 1835 – 1838. Bath Poor Union Workhouse was a “Y” plan.

N. B. You can find out more about who is buried at Frome Road Workhouse at the BRO Bath Union Workhouse page.

Cemetery

Abbey Cemetery

Bath Abbey, which dates back to 1499, sits on the remains of a massive Norman cathedral. Since that time thousands of people have been buried under the building, in fact it is estimated that up to 6,000 bodies are in shallow graves under the church’s grave ledger stones. Recently this has caused stability issues with the abbey floor.

By the 1830s it was clear that there was a lack of cemetery space in Bath and proposals for a new public cemetery were circulated.[15]

By 1842 The Reverend William John Brodrick (1798 – 1870) who was Rector of Bath from 1839 – 1854 had purchased some land for a new cemetery.[16] He paid between £3,000 and £4,000 for the land but took the fees whilst he was Rector of Bath.

Interestingly Reverend William John Brodrick was the second son of Charles Brodrick, Archbishop of Cashel and Emly in co. Tipperary. He became a chaplain to the Queen[17] and Dean of Exeter but he also succeeded his brother Charles Brodrick (1791 – 1863) to become 7th Viscount Midleton of Midleton in the County of Cork.

He married in March 1824 Lady Anne Elizabeth Brudenell, eldest daughter of the 6th Earl of Cardigan (whose son led the Charge of the Light Brigade) but she died on 24th November of the same year. In 1829 he married the Hon. Harriet Brodrick, fourth daughter of the 4th Viscount Midleton. He was raised to the rank of a Viscount’s son by Royal Warrant in 1849.

The design of the cemetery was by John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843), a celebrated Scottish botanist, garden designer and cemetery designer, author and garden magazine editor. The chapel was designed by the Surveyor of Works for the Bath Corporation from 1823 to 1862, George Phillips Manners (1789 – 1866) in the Anglo-Norman style. It was built by James Birth, a mason who lived in Belvedere.[18]

Lucy Rutherford has described Bath Abbey Cemetery as “The Forgotten Necropolis” and says:

“..In its early years the Abbey cemetery was a fashionable and profitable enterprise which, according to Brodrick’s return for the 1851 Ecclesiastical Census, was bringing in an annual income of £500 within seven years of opening. In common with most Victorian cemeteries, however, profits inevitably declined as burial space was used up and cremations grew in popularity. Following the Second World War, the Abbey cemetery faced a period of sustained decline. Church working parties attempted to carry on the necessary maintenance during the 1970s and ’80s, but these were unable to stem the growing tide of brambles and weeds. After the sale of the cemetery lodge in the 1960s there was no longer a permanent caretaker, leading to regular episodes of vandalism and the theft of gardening equipment, and the chapel itself became increasingly unsound. In 1995 the cemetery was formally closed and responsibility for its maintenance transferred to the then Bath City Council, in accordance with the provisions of the Local Government Act 1972...”[19]

N. B. You can find out more about who is buried at Bath Abbey cemetery via the BRO Bath Abbey Cemetery Page

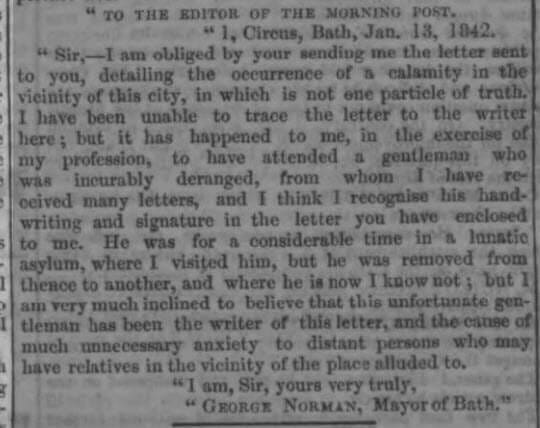

Hoax in 1842

1842 hoax

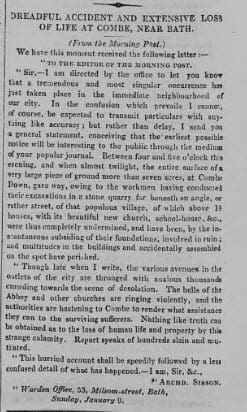

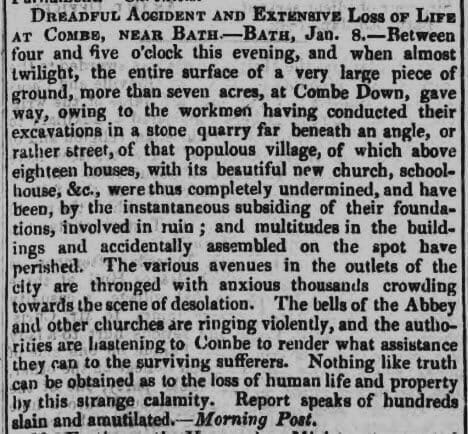

In 1842 reports were published in various newspapers of “hundreds slain and mutilated”.

Former quarryman and Coleford resident, Antony Comer found fascinating newspaper reports dating back to January 1842 about a ‘dreadful accident’ and an ‘extensive loss of life’ on Combe Down.

A letter was received by the Morning Post on Jan 10 1842, published and picked up by other newspapers.

Part of it states there was a ‘loss of human life and property by this strange calamity’ and there were reports of ‘hundreds slain and mutilated’.

The letter, signed by an Archd Sisson, reads:

“Sir,– I am directed by the office to let you know that a tremendous and most singular occurrence has just taken place in the immediate neighbourhood of our city (Bath).

In the confusion which prevails I cannot, of course, be expected to transmit particulars with anything like accuracy; but rather than delay, I send you a general statement, conceiving that the earliest possible notice will be interesting to the public through the medium of your popular journal.

Between four and five o’clock this evening (January 9), and when almost twilight, the entire surface of a very large piece of ground, more than seven acres at Combe Down, gave way, owing to the workmen having conducted their excavation in a stone quarry far beneath an angle or rather street, of that populous village, of which above eighteen houses, with its beautiful new church, school-house &c., were thus completely undermined, and have been, by the instantaneous subsiding of their foundations, involved in ruin; and multitudes in the buildings and accidentally assembled on the spot, have perished.

Though late when I write, the various avenues in the outlets of the city are thronged with anxious thousands crowding towards the scene of desolation.

The bells of the Abbey and other churches are ringing violently and the authorities are hastening to Combe, to render what assistance they can to the surviving sufferers.

Nothing like truth can be obtained as to the loss of human life and property by this strange calamity. Report speaks of hundreds slain and mutilated.

This hurried account shall be speedily followed by a less confused detail of what has happened.”

The papers soon realized that it was a hoax.