I’ve added a section about the Curo cable car plan that flew across the sky between 2015 and 2017.

Curo were starting the development of Mulberry Park and having some ‘issues’ with their Foxhill master plan – which was mentioned in last month’s blog ‘Black hats or blunderers‘.

The Curo cable car plan was abandoned after negative feedback during the consultation process. What I find interesting is why it was put forward? Did Curo really believe that it would receive planning permission in Bath’s World Heritage Site?

Curo are members of the World Heritage Site steering group which also includes:

- Bath & North East Somerset Council

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport (receive papers but do not attend)

- Historic England

- ICOMOS UK

- The National Trust

- Bath Federation of Residents’ Associations

- Bath Chamber of Commerce

- Bath Preservation Trust

- Bath Business District

- Bath Primary Schools

- University of Bath

- Bath Spa University

- Bath Tourism Plus

- Bath Charter Trustees

- Avon Local Councils Association

The World Heritage Site steering group is involved with producing the Bath World Heritage Site Management Plan.

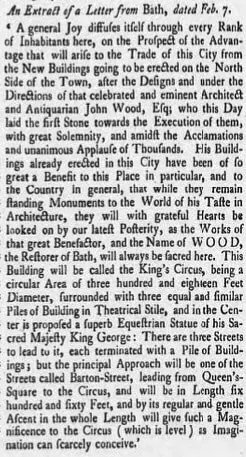

A quick review of this would have shown the obstacles that the Curo cable car plan would have faced in getting any planning approval. Presumably why they said they intended to bypass the usual planning system and go straight to the Secretary of State for Transport.

Even that, one suspects, would have been a challenge. As the Bath World Heritage Site Management Plan makes clear:

"Government guidance on protecting the Historic Environment and World Heritage is set out in National Planning Policy Framework and Circular 07/09. Policies to protect, promote, conserve and enhance World Heritage properties, their settings and buffer zones are also found in statutory planning documents. The Bath and North East Somerset Local Plan contains a core policy according to which the development which would harm the qualities justifying the inscription of the World Heritage property, or its setting, will not be permitted. The protection of the surrounding landscape of the property has been strengthened by adoption of a Supplementary Planning Document, and negotiations are progressing with regard to transferring the management of key areas of land from the Bath and North East Somerset Council to the National Trust."

Further reading would have shown:

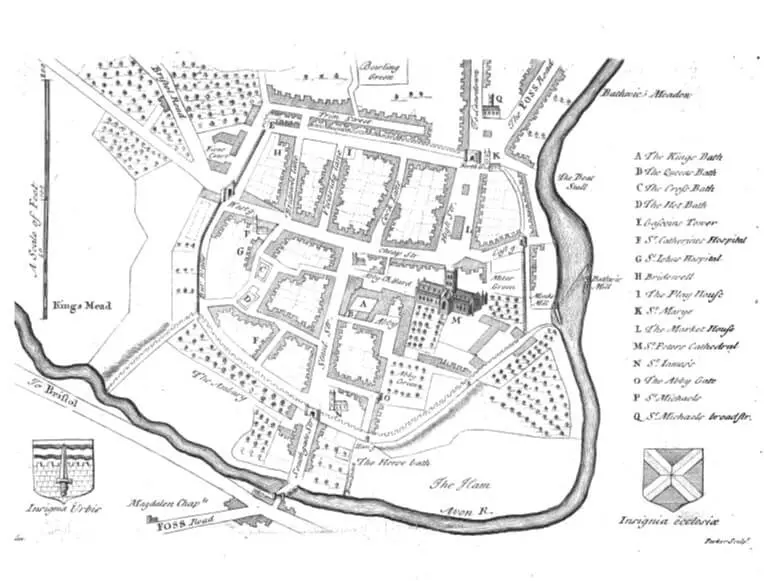

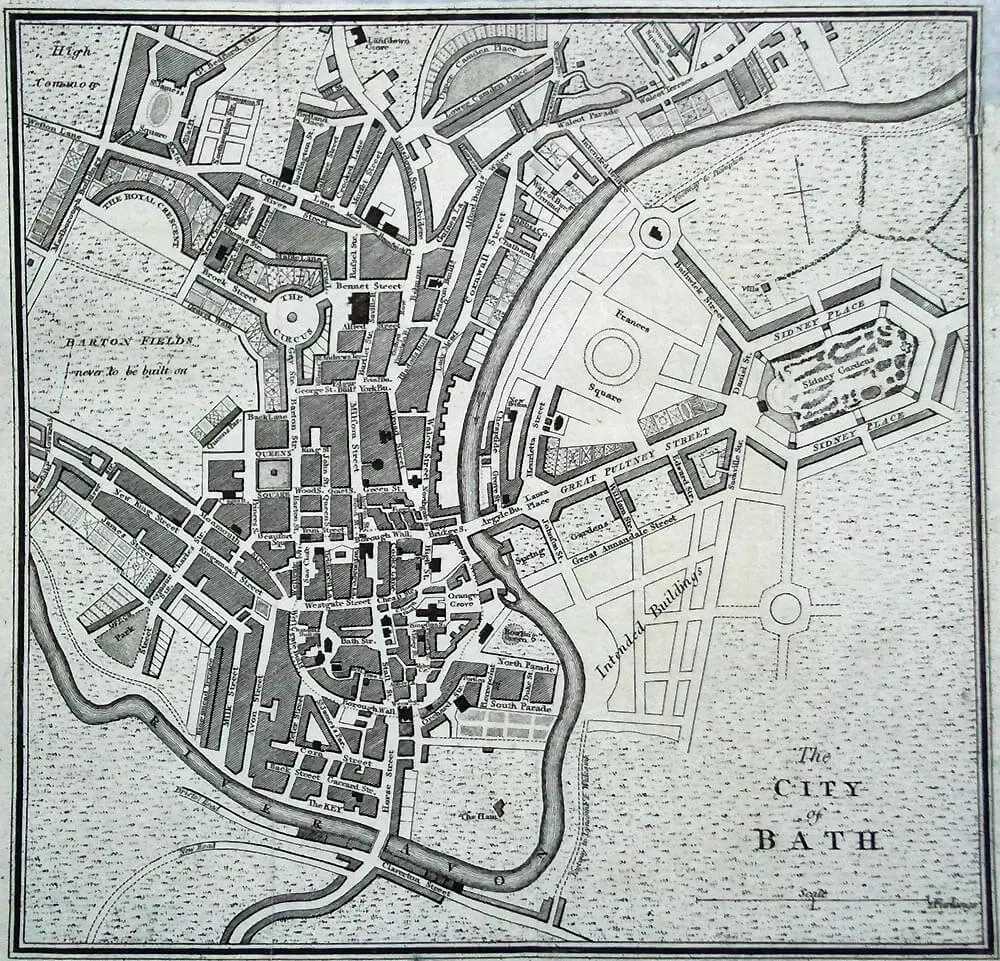

"The site boundary is the municipal boundary of the city. This covers an area of approximately 29 square km. As noted in chapter 1, Bath is exceptional in this respect as the World Heritage inscription in almost every other city worldwide covers only a part of the urban area and not the entire settlement. Venice and its lagoon is the closest European comparator. The property was inscribed in 1987 without a boundary map, which was not uncommon at that time. The description of the ‘City of Bath’ was taken to mean that the boundary encompassed the entire city and it was managed accordingly. This boundary was subsequently confirmed by letter (dated 17 October 2005) from the UNESCO World Heritage Centre."

and:

"Bath remains a compact city, contained largely within the hollow in the hills as previously described. The city does not have significant ‘urban sprawl’ and high quality built development directly adjoins high quality landscape at the urban edge. The skyline is predominantly characterised by trees or open pasture. The green hillsides provide a backdrop to the urban area and are visible from most of the city centre. Bath is well provided for in terms of parks and open spaces, with the River Avon cutting through the city centre providing natural beauty and sense of calm. All of the above contribute to an impression that the city is smaller than it actually is."

and:

"The Green Setting of the City in a Hollow in the Hills 42. The compact and sustainable form of the city contained within a hollow of the hills 43. The distinct pattern of settlements, Georgian houses and villas in the setting of the site, reflecting the layout and function of the Georgian city 44. Green, undeveloped hillsides within and surrounding the city 45. Trees, tree belts and woodlands predominantly on the skyline, lining the river and canal, and within parkland and gardens 46. Open agricultural landscape around the city edges, in particular grazing and land uses which reflect those carried out in the Georgian period 47. Fingers of green countryside which stretch right into the city"

as well as various maps:

So, why was the Curo cable care plan put forward? It would seem that it was most unlikely to get planning permission – unless there’s something I don’t know about.