It was the sort of strange coincidence that seems to call for an alliterative mass market magazine headline, something like “Mattingley makes Maria match” or “Strange Scammell story sensation” but ‘Combe Down cousin coincidence’ got the vote.

You may be wondering what I’m on about, or, even, what I’m on?

Actually, it’s quite simple but a bit strange. I discovered, quite by chance after we have lived here for 31 years, that my (half) brother Phil Scammell’s 1st cousin 4 times removed, used to live next door, at 117 Church Road Combe Down, in 1870/71.

Not only that but her son, Robert Henry Mattingly, was born there in 1870 and her husband, Robert George Mattingly, died there in 1871.

Strangely, I wrote about them, Robert and Maria Mattingly, in my book and on this site, saying “Robert (b.1841) and Maria Mattingly (1841 – 1921) lived at 117 in 1871. Robert had been a joiner but no more has been discovered about them.”

That was because I didn’t know then that Maria was Maria Scammell (1840 – 1901).

That I discovered when David Gardner, an expert on the Scammell family tree, contacted me to gently point out some errors in the family tree I publish and update from time to time.

He also commented ‘Maria c 1841 who died 1901 Barnet her spouse was Robert G Mattingley’. At the time a very soft chime went off in my head, but I did not, then, make the connection.

Then about a week later, considering what to post about for Prior to Now this month, I was paging through the site and saw Robert and Maria Mattingly. The surprise and the connection were instant and, after doing some more digging into the family tree on Ancestry I was able to confirm that they are, indeed, the same people. It’s a bit weird somehow.

Maria was the daughter of Joseph Scammell (1801 – 1875) and Maria Slade (1805 – 1895), who were both born in Edington, Wilts.

Joseph had been a farmer in Ringwood according to the 1841 census, a rail timekeeper at Eling St Mary in the 1851 census but who, by the 1861 census gave his occupation as a “farm bailiff of 160 acres employing 4 men and 2 boys” and was living at 26 Bearfield, Bradford on Avon. Maria had been born whilst he was at Ringwood and in 1864 married Robert George Mattingley (1841 – 1871) in West Derby on Merseyside.

Robert had been born in Chippenham, was a joiner and had, presumably, found work up there. He died aged only 30 at 117 Church Road, Combe Down.

Robert and Maria had 3 sons, Henry Nelson Slade Mattingley (1865 – 1946), George Elliot Mattingly (1867 – 1887) and Robert Henry Mattingly (1870 – 1895).

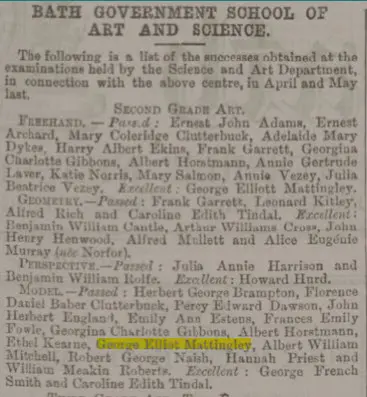

We know that George Elliot Mattingly was born in Liverpool and attended the Bath Government School of Art and Science from an entry in the Chronicle for 1885.

The school was then at 33 Paragon, opposite The Star Inn and later came under the umbrella of the Bath Technical Schools and is now Bath School of Art and Design part of Bath Spa University. Unfortunately he died just 2 years later at the age of 20.

Robert Henry Mattingly was born at 117 Church Road, Combe Down and died when he was only 25. He was an auctioneer’s assistant and lived at 23 Milsom Street, the ground floor of which was Lloyds Bank. He left £127 6s according to probate, a considerable sum for such a young man.

Henry Nelson Slade Mattingley was also born in Liverpool but was baptised in Chippenham. In the 1881 census his occupation is Apprentice Bookseller. He married Edith Mary Butterfant (1866 – 1946) in 1890 and in the 1891 census when he was living in Lakenham his occupation was given as ‘Manager, Fancy Goods Dept.’.

He moved to Barnet by 1901 and became a Commercial Traveller. When he died at Middleton on Sea in 1946 he left £9,919 14s 6d worth between £367,500.00 (commodity value) and £1,846,000.00 (income or wealth value) today, depending on how it’s calculated.

He and his wife had 2 children Nelson Robert Eric Mattingley (1899 – 1986) and Geraldine Mattingley (1900 – 1976). Nelson Robert Eric Mattingley is shown as a schoolboy boarder at Monkton Combe Junior School, Combe Down, Bath in the 1911 census.

Maria died in 1901, leaving £747 8s 8d. She had home in Bath, at 3 George Street, and in Barnet, presumably to be near her remaining son Henry Nelson Slade Mattingley.

So, there you go, nothing earth shattering just a coincidence but one I, at least, found quite interesting.