ABOUT JOHN DANIELS

John was born and bred in Bath, He grew up in Lower Weston and was gained his degree at University College London in Economics and International Relations. He joined the Board of Trade and he did a range of civil service jobs. he has lived in Sutton, Surrey with his wife Carole. They have 2 children and 4 grandchildren who live locally.

In retirement, after publishing a biography on his grandfather Frank Pine and his Uncle Robert Daniels’ families’ lives on Combe Down, he published a book on the Chelsea Road area of Bath in which he grew up. He then did a book on the Bath Hospital Box Scheme, followed by a history of Banstead Musical Theatre (reflecting his, and his wife’s, long membership). He is now engaged on a book on the Daniels family’s ancestral village of Littleton Drew, Wiltshire.

© John Daniels 2017. The right of John Daniels to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part may be reproduced, adapted, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the author or publisher.

INTRODUCTION

‘Saving our hospital’ could have been a headline in any of the last few years, as the Covid 19 pandemic of 2020 forced the world to return to ancient methods of quarantine and confronted us with the limits of modern medicine.

It has brought the issues of public health provision to our attention – and the role of the state in providing and funding it.

Most of all it has led to world-wide acclaim for the health professionals who deliver national health services like the NHS. But what happened before the NHS?

This essay looks at national trends from the perspective of the financing of health services in Bath in the early twentieth century with regard to philanthropy, mutuality and voluntarism, and the Bath Hospital Box Scheme’s many supporters.

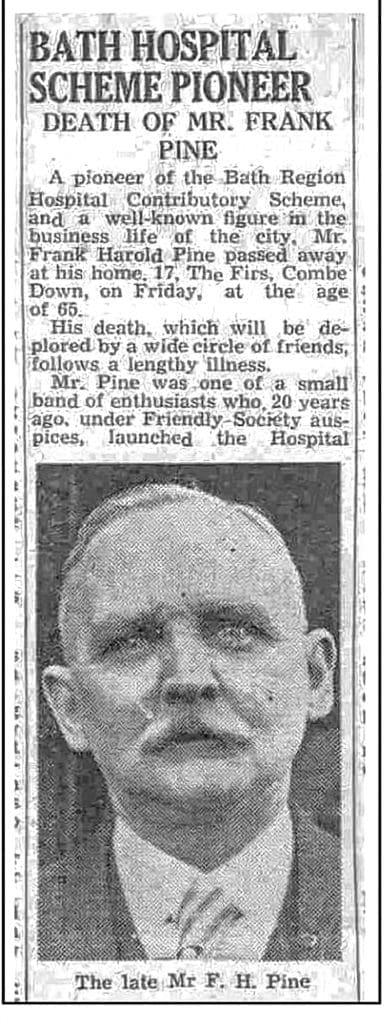

My interest in this stems from the fact that I was born and bred in Bath – but more especially because my maternal grandfather Frank Pine had much to do with these issues in the 1920s and 1930s.

For most of this period he was President of the local branch of the Hearts of Oak Friendly Society. From 1922, for 10 years or more, he was Chairman of the Bath Council of Friendly Societies and Chairman of the contributory Box Scheme that had the slogan of ‘Saving Our Hospital’ and the objective of rescuing the Royal United Hospital (RUH) Bath from debt and the risk of closure.

This facilitated its removal in December 1932 from a cramped hospital in the centre of Bath to new premises at Combe Park, Bath.

Also, during this period, Frank Pine was Chairman of the local council on Combe Down whilst working as an accountant with two local companies – Bath and Somerset (Norton) Dairies and Spear Brothers and Clark.

From March 1934 until his death in April 1942, he was a member of the RUH Management Board.

BATH’S CHARITABLE (VOLUNTARY) HOSPITALS

Early hospitals in Bath (St John’s dating from the twelfth century, St Catherine’s founded in 1522 and Bellott’s Hospital founded in 1608) provided some medical and nursing care but were essentially alms houses for the elderly and impoverished.

Before the growth of Bath (through wealthy visitors from the mid eighteenth century) the population of about 2,000 was too small to support a hospital.

The Bath General Infirmary was founded in 1737 and incorporated in 1739. It was also known as The Mineral Water Hospital.

Queen Victoria conferred on it the ‘Royal’ title in 1888.

In 1935 it became the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Disease (RNHRD).

As a national specialist hospital taking patients from far and wide it did not find it easy to raise funds locally – but in 1948 it was taken over by the NHS with a substantial dowry of investments.

From the mid-eighteenth century a number of voluntary hospitals were founded by rich benefactors to provide medical assistance for the poor.

However, initially the Royal Mineral Water Hospital was only open to visitors from outside the city.

In 1747 the Bath Pauper Trust was founded to raise money for local people needing medical advice and assistance. This led to the establishment of the Bath City Infirmary and Dispensary.

The scale of Bath’s building boom created a heavy demand for an accident and emergency service, and in 1788 a new casualty hospital opened in Kingsmead Street. In 1826 a new building was built to accommodate a merger of the two hospitals to be called the ‘Bath United Hospital’.

In 1864 new wards were built and named after the Queen and her late consort. She bestowed the ‘Royal’ title on the hospital. The purposes of the Royal United Hospital (RUH), as they remained into the 1930s, were to provide “For the relief of the poor of the city and neighbourhood and for giving immediate assistance in all accidents”.

The RUH is pictured here in 1910 at its increasingly cramped Beau Street premises.

Other voluntary hospitals in Bath were the Bath Eye Infirmary that was established in 1811 and the Bath Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital that was established in 1837.

Hospitals, whether they were a workhouse infirmary or a leading voluntary hospital, were founded and funded by the middle and upper classes. The aim was to serve the needs of the working-class population without charge.

Dispensaries for the poor also offered some medical advice and medicines. Bath had 4 main dispensaries – The City, Southern, Western and Eastern dispensaries.

WHAT WAS A VOLUNTARY HOSPITAL?

Voluntary hospitals were based on charitable donations by wealthy subscribers. They were for the benefit of the poor – whom doctors treated for free (but subscribers could issue tickets of entitlement).

Until 1905 the RUH issued subscribers tickets. It then was decided that only doctors should approve admissions.

Until the NHS the RUH was still, in principle, for the benefit of the poor.

Voluntary hospitals had a teaching role and focussed on acute cases. In a sense doctors could practice on the poor before attending to their paying patients!

Chronic cases often ended in the workhouses, although by the Great War the stigma of workhouses was being reduced.

Florence Nightingale’s pressure for proper workhouse nursing had had some effect. Indeed Bath workhouse became a training establishment for nurses.

WHAT OTHER HOSPITALS WERE THERE IN BATH?

The voluntary hospitals had no monopoly on care, and before the NHS both local government and the Poor Law also provided hospitals that were in principal free to use.

Asylums for psychiatric patients were overseen by the county councils.

Following the 1866 Sanitary Act, municipal and district councils established many isolation hospitals – such as the

Bath Statutory Hospital for Infectious Diseases, Claverton, which opened in 1876.

The Workhouse Infirmary on Combe Down was rate funded under the Poor Law. After 1914 it was known as Frome Road House and the Workhouse sign was taken down.

Florence Nightingale did a great deal to ensure professional nursing in workhouse infirmaries (and published a book on the subject).

In 1914, in order to recruit and retain trained nurses (by registering as a training establishment) the Infirmary recruited a full time medical officer. Frome Road Infirmary evolved into the Municipal Hospital of St Martins that, like the RUH, was absorbed into the NHS.

Private hospitals for paying middle class patients evolved in the 1920s – the RUH Private Hospital that opened in 1924 was soon named the Forbes Fraser Private Hospital (after a recently deceased and celebrated RUH surgeon).

It became the country’s second largest private hospital. Its aim was to provide treatment for middle class people who could afford to pay – but who could not afford expensive nursing home fees.

Forbes Fraser died before he could pursue his vision for the RUH as a hub of local cottage hospitals.

Other hospitals established at Combe Park were the War Hospital/Ministry of Pensions Hospital built during the Great War (that in due course served as a nurses’ home), and the Orthopaedic Hospital that opened in 1924 (along with the Forbes Fraser Private Hospital – both were built on one level with scope for expansion), and the Second World War American Hospital that became the Manor Hospital.

THE GROWING DEMAND FOR HOSPITAL TREATMENTS AFTER 1850

In the early Victorian period, a hospital was a place that those who could afford private medical treatment at home or at a nursing home would seek to avoid like the plague (or whatever diseases they harboured there)!

But that was before Florence Nightingale made nursing a profession from the 1860s onwards (with a new breed of matrons as hospital managers). Surgery became safer through the use of anaesthetics from the late 1840s, and the development of anti-septic and aseptic techniques in the 1870s and 1880s.

As standards of hygiene, treatment and care steadily improved in hospitals and workhouse infirmaries (and their numbers increased), people who were not paupers started to use their facilities.

PHILANTHROPY AND VOLUNTARISM

The philanthropic basis of the funding of the voluntary hospital system was not exactly altruistic.

As was the common practice with most voluntary hospitals, every year the wealthy subscribers to the RUH were allocated ‘tickets of relief’ according to how much they had contributed, and they would in turn hand these out to those they considered most in need of treatment – or wished to patronise!

This ticket system lasted until 1905 when the RUH management decided that admission should be authorised by doctors instead.

From the 1890s onwards some hospitals appointed lady almoners to see if patients could afford to pay for treatment. An almoner was not appointed at the RUH until 1913 (when a Mr Humphries was appointed). These almoners soon developed a social welfare role.

FRIENDLY SOCIETIES & MUTUALITY

In the 19th century the Friendly Societies had a major role – from Freemasonry to Mutuality and to the establishment of trade and craft unions.

Friendly society branches in Bath were key players in the story of the Bath Hospital Box Scheme.

At the turn of the 19th century friendly societies were having a great deal of success in recruiting new members with a range of benefits in the event of ill health, death or unemployment.

By the 1890s many skilled workers had joined friendly societies for such schemes. The society branches combined this mutuality with a strong social side for their (male) members.

Before the Great War these branches hosted many male middle-class dinners and excursions – albeit with the odd talk on benefits. That ethos disappeared after the Great War – especially with women more active on health issues.

With a range of health and unemployment benefits the societies feared state intervention could threaten their mutuality.

In 1899 the Bath Council of Friendly Societies was formed from the ten local branches of the nation-wide societies.

This was to co-ordinate local responses to government initiatives that might intrude on what the friendly societies saw as their role – issues such as workmen’s compensation for injuries, pensions and national insurance.

The National Insurance Act 1911 impacted on the societies’ role.

Although it did not extend to hospital care or to wives and children, it was a major step in healthcare. In roping in the Friendly Societies to collect payments and pay benefits under the Act, Lloyd George thought he was doing them a favour. In fact, getting involved in government regulation was the undoing of the friendly society movement.

VOLUNTARY HOSPITALS FACE FUNDING ISSUES

Towards the end of the 19th century, voluntary hospitals like the RUH were finding it hard to make ends meet (with subscriptions from wealthy donors drying up).

Contributions were therefore sought from working men through company schemes like Stothert & Pitts or Saturday or Sunday Clubs (paying a Saturday’s pay once a month to a hospital or contributing to collections at Church).

In 1907 the Mayor of Bath Sydney Bush mounted a successful campaign, aided by a League of Help, to wipe out the hospital’s accumulated debt.

But that was short lived, the League of Help folded (thinking its job had been done) and deficits soon arose to create new debt.

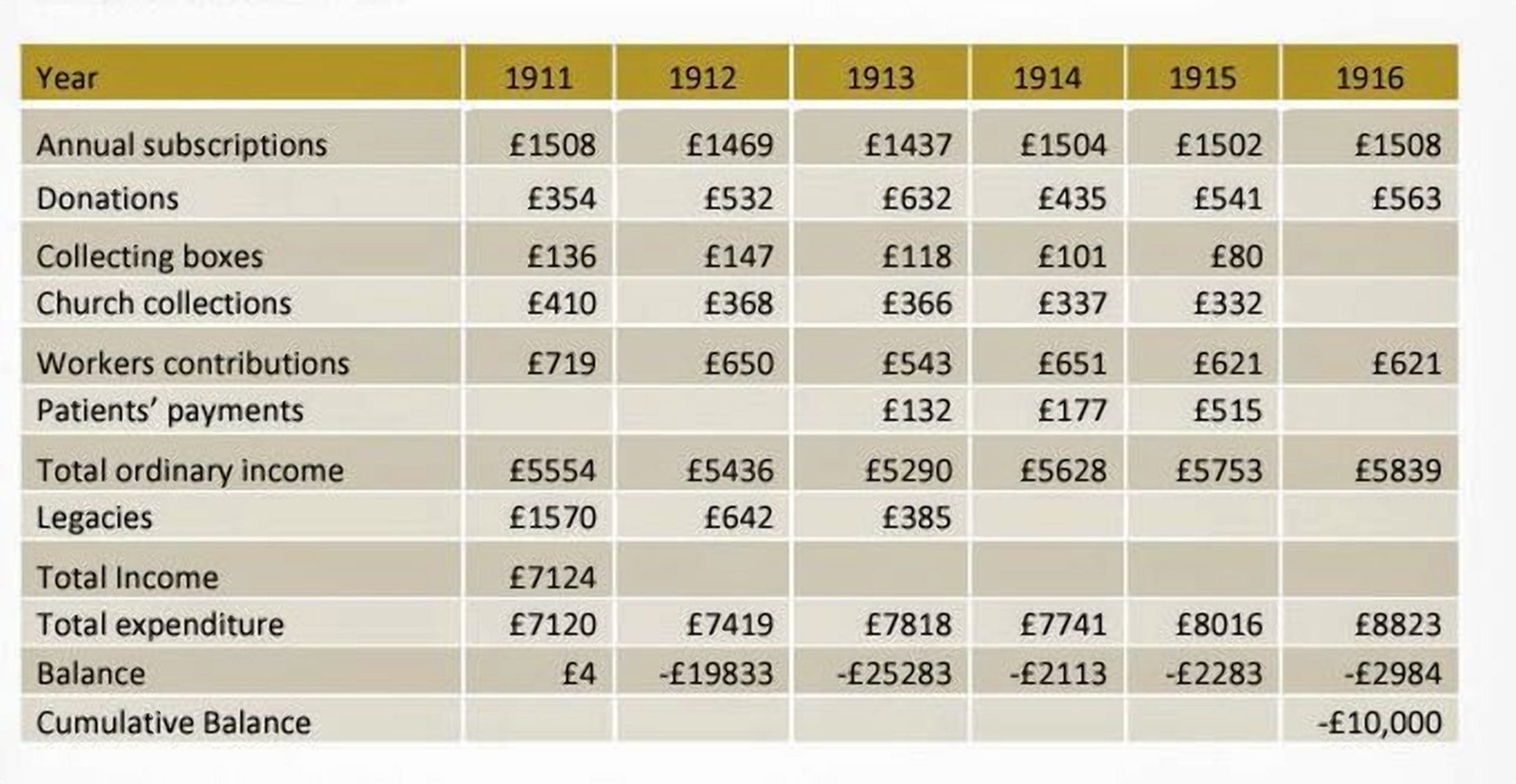

The following table shows – from 1911 to 1916 – static charitable income from the wealthy and rising costs leading to a large cumulative deficit.

HOPES FOR A NEW APPROACH TO HEALTHCARE DASHED

The Ministry of Health Act 1918 established the Ministry of Health in 1919 (at the peak of the Flu Pandemic in which Bath suffered badly). Its role was to ‘take all such steps as may be desirable to secure the preparation, effective carrying out and co-ordination of measures conducive to the health of the people’.

Expectations were raised of greater state funding of hospitals and health services and the expansion of National Insurance to cover hospitals and dependant wives and families.

The head of the new ministry looked to more pro- active public health & preventative measures. Some might have dared to hope something like NHS might arise.

Although Government payments during and after the war up to 1921 (mainly for war wounded) had helped hospital finances, these dried up in 1922 as a result of the Geddes Axe (government expenditure cuts – the first time the term was used).

This ushered in an era of austerity and dashed the hopes placed on the new ministry.

THE NEED FOR A NEW APPROACH

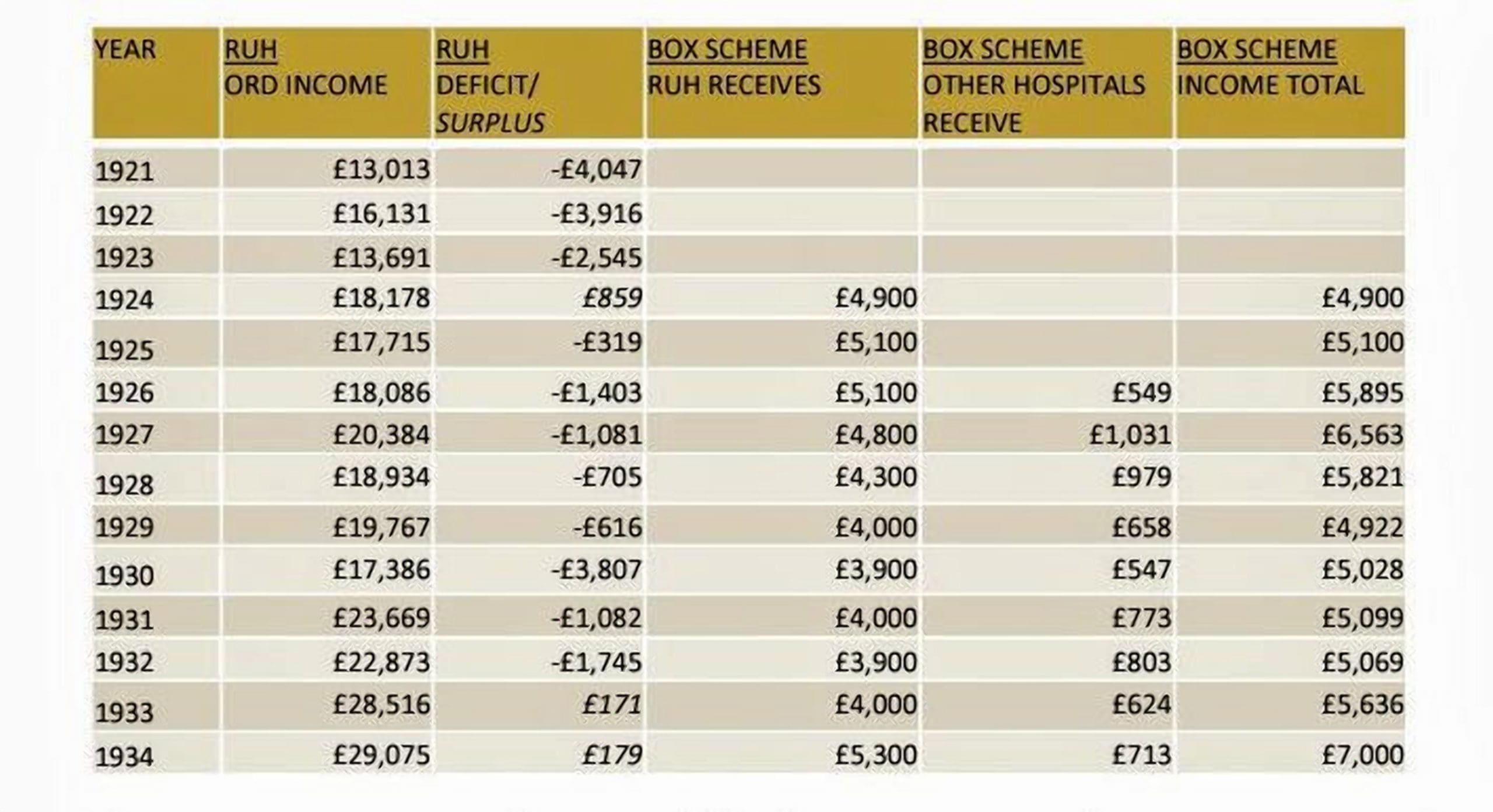

At the end of 1922 the RUH had an annual deficit of nearly £4,000 making a total cumulative deficiency of £10,313.

So, by the early 1920s a new approach was needed as it became clear that the hospital would not last long if it had to resort to selling its investments and other capital assets bequeathed by past benefactors.

This is where the Bath and District Contributory Scheme (the Box Scheme) came in.

It was promoted by the Bath Council of Friendly Societies chaired by my grandfather, Frank Pine.

Key players in the Box Scheme included: HC Lavington, W Amesbury, WH Chorley, HF Fiddes, AS Gunstone, G Haverfield, GS Hodges, WA King and F Knight .

After Geddes ‘Save Our Hospital’ became the clarion call of Contributory Schemes for Voluntary Hospitals throughout the country.

It was certainly the theme for the Bath scheme which was based on a successful scheme in Canterbury.

The range of political philosophy involved in terms of hospital funding was:

1. Support for Voluntarism, Philanthropy and Mutuality and ‘the human touch’ that would be lost with bureaucratic control – through contributory schemes.

2. Hospitals on the rates: developing Municipal Hospitals (to encompass voluntary hospitals) as was favoured by the Labour Party. Over half hospital beds were former Workhouse Infirmaries that became Municipal Hospitals.

3. State funded hospitals as in Germany – a cause espoused by the Liberal Party at its conference in Bath in 1938.

A 1920 proposal in Bristol for the amalgamation of the medical charities of Bristol, including the six major voluntary hospitals of the city ultimately failed. Bristol did not fully embrace local contributory schemes until the 1940s (see “Co-operate! Co-ordinate! Unify!” by Prof George Gosling).

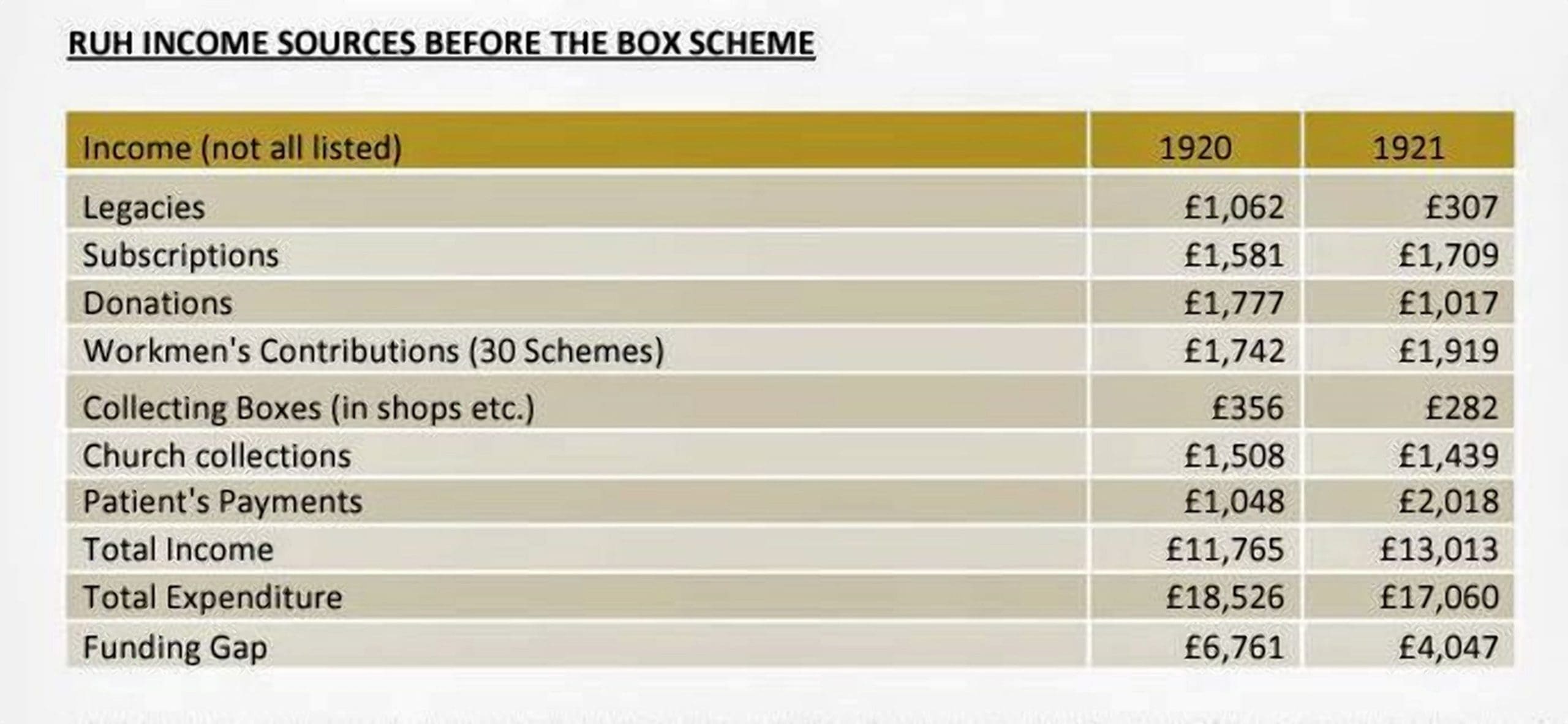

RUH INCOME SOURCES BEFORE THE BOX SCHEME

I don’t have full figures for 1923 but the above table shows the varying contributions of charity to RUH funds. These figures indicate the funding gap that the Box Scheme sought to address.

Workmens’ contributions from 30 schemes rose to over £2,000 in 1924 and 1925 but fell to £1,800 in 1926 and 1927.

Of these contributions, the 10% received from the Somerset Miners disappeared completely after the 1926 General Strike. In due course these workplace schemes were brought into the Box Scheme arrangements. Patients Payments rose to around £4,000 in 1924, 1925 and in 1926 rising again to £4,800.

THE OBJECTIVES OF THE BOX SCHEME

The objectives of the Box Scheme seemingly accorded with the Friendly Societies’ approach in providing society benefits and in administering contributions and benefits under the 1911 National Insurance Act.

It was hoped that raising £5,000 per annum (about £300,000 now) would enable the hospital to pay its way if boxes were put in 12,000 homes for weekly donations of 2d a week.

In 1929 many people began to increase their contributions to the Box Scheme from 2 pence to 3 pence a week because this allowed them to be relieved of questions as to means by the almoners. By 1943 everyone was encouraged to pay 4 pence a week. By the end of 1922 some 2,500 boxes were already in use. By 1938 there were 16,000 subscribers to the Box Scheme.

So working men contributed to a scheme to fund a hospital that should have been free to them – but that was because they feared that the alternative was that there would be no hospital when they needed it!

THE MANAGEMENT OF THE BOX SCHEME

The Box Scheme was, in the end, highly successful – but a promising start in 1923 was affected by the impact of the 1927 recession.

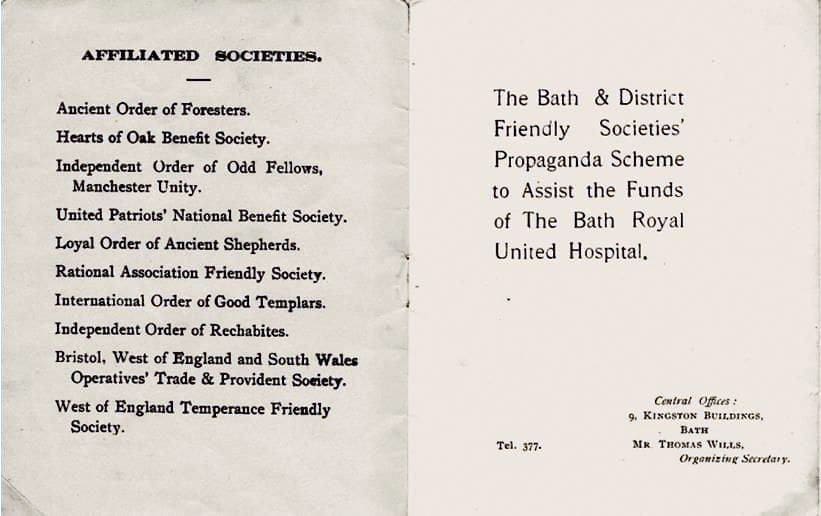

The scheme was officially called the Bath & District Friendly Societies’ Propaganda Scheme to assist the Funds of the Bath Royal United Hospital.

According to its original rules of 1923 the scheme aimed at collecting annually for the Hospital, the sum of £5,000 (significantly more than its current annual deficit of £4,000). In its implementation the scheme would be known as The Bath and District Friendly Societies’ Household Collecting Box Scheme.

Whilst the bulk of its payments went to the RUH, other local cottage hospitals soon became part of the scheme (although in 1932 Chippenham withdrew from the scheme, considering its payments stingy).

Payments, on behalf of scheme members, were also made to hospitals in Bristol and other UK hospitals (including several in London).

By July 1938, given its coverage of treatment at other hospitals, it was officially known as The Bath Region Hospital Contributory Scheme. The management of the scheme was to be firmly in the hands of the Bath and District Friendly Societies’ Council whose members were nominated by the ten affiliated friendly society branches. So there was a bit of a democratic deficit.

The Council was to set up and to work the scheme independently of the Hospital Managing Board, having its own Offices and Administration. It would be the Central Body to receive reports, to consider and resolve on all matters connected with the scheme, and for this purpose it might co-opt one representative to be nominated by each District Committee.

In the original rules, only the Friendly Societies Council could appoint a paid organiser and staff for the scheme.

However, the rules required that, at least once every quarter, the Council would be obliged to submit to the Hospital Managing Board a report of the results of the collections and general working of the scheme. So, the Hospital Managing Board had some oversight of the scheme.

PROMOTING THE SCHEME

The rules provided that a Central Executive was to be set up, and consist of five members appointed by the Council, together with the Hon. Treasurer, the Hon. Secretary, and the Chairman of the Hospital Managing Board. The Executive was to act on behalf of the Council in calling Public Meetings at the centre or in the Districts to explain the Scheme.

With the help of the Mayor of Bath, and local mayors and councillors, District Committees were eventually set up in 21 Bath wards, and 35 districts in Somerset and 31 localities in Wiltshire – in the hinterland of the hospital. Each district had a chairman, secretary and treasurer and a fair number of voluntary stewards. Collecting boxes were distributed to houses in each area by the stewards who would return and empty them and account for their contents each quarter.

In 1927 there were over 1,200 stewards and in 1933 the initial print run of ‘Our Hospital’ magazine for distribution to the stewards was for 5,000 copies. Bringing employers’ schemes in under the banner of this main scheme began in the 1930s and by 1939 about 80 employers were covered.

IMPORTANCE OF CEDRIC CHIVERS, MAYOR OF BATH

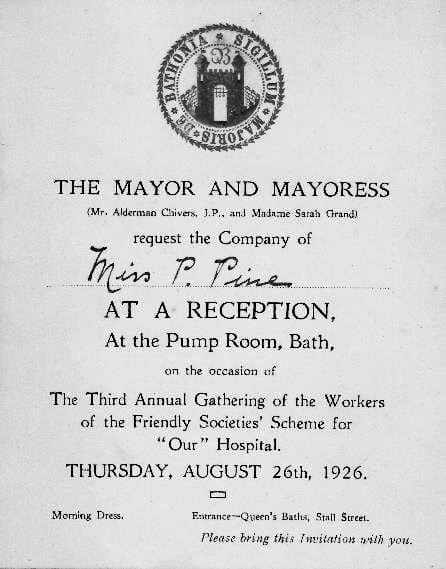

Here I would like to pay tribute to one of the great Mayors of Bath whose part in promoting and setting up the Box Scheme was crucial.

He was 6 times Mayor of Bath in the 1920s.

A bookbinder, he championed women designers.

He established and endowed Bath public library. He supported the Bath Cabinet Makers workers co-operative.

A Liberal – he joined with the Trades Unions in forming Bath Trades Council.

A Widower: he chose the Suffragist author Madame Sarah Grand as Mayoress.

Chivers and Grand jointly gave great support to the Box Scheme (attending ward meetings and hosting annual Guildhall or Pump Room Receptions for the unpaid officials of the scheme).

He argued that those who contributed a substantial sum to the hospital ought to have a larger voice in its management.

By June 1928 the Hospital Box Scheme had 6 representatives on the RUH Management Board.

He established a fund for a New RUH in Combe Park.

He died in office 1929 – and George Bernard Shaw sent a tribute.

His successor Aubrey Bateman (another great Mayor) described Chivers as the greatest Bathonian in living memory.

MEETINGS AND FOOT SLOGGING

The scheme imposed a considerable burden on the friendly societies to recruit people in Bath and the surrounding towns and villages of north Somerset and west Wiltshire that used the hospital (something like 200,000 inhabitants).

Representatives of the friendly societies had to make frequent visits in the area to encourage the setting up and enthusiastic running of local committees, and recruiting stewards to collect money from the boxes.

My grandfather Frank Pine spent much of his spare time visiting towns and villages promoting the scheme. On Sundays he often showed recruits or potential recruits to the scheme around the RUH.

He also was a leading speaker in support of the scheme at a number of major meetings.

As noted above, stewards and other unpaid officials of the scheme were rewarded by invitations to an annual reception, hosted by the Mayor of Bath at the Guildhall or the Pump Room – with speeches, food, drink, music and dancing.

Other entertainments might include visits to the Roman Baths.

In May 1925 some 850 invitations went out and 700 attended. In 1927 the invitations numbered 1,400.

THE ROLE OF WOMEN

The Box Scheme extended to whole families so it had a great appeal to women as only a few women were covered by National Insurance.

In 1905 when the RUH ended the need for subscribers tickets and sought increased workplace contributions, and also to endorse the role of women fund-raisers, 3 working men and 3 women were elected to the RUH Management Board.

One of the 3 women elected to the RUH Board in 1905 was Mrs Latter Parsons.

Widowed in 1901 She became a City Councillor in 1921 (she was chairman of the Maternity and Child Welfare Committee from 1926).

She served on the RUH Board until well into the 1930s.

She died on 3 February 1944.

In 1928 The Box Scheme was asked to appoint 6 members to the RUH Management Board.

One of the two women appointed was the Hon Mrs Shaw-Mellor. She was a Vice-Chairman of the RUH Board from 1932-7 and RUH Chairman for 3 years from 1937-1941. Married to a GP with two daughters she lived at Box House, Box, Wiltshire!

FUND RAISING BY THE BOX SCHEME: THE FIRST 10 YEARS

In May 1925 it was reported that the friendly societies had raised £4,900 in the preceding year.

This was a little short of the target of £5,000 but it was an encouraging start: the hospital was able to show its first credit balance for a great many years.

The cost of working the scheme was 5% of receipts (in 1934 this peaked at 9% before falling back to 7% in the late 1930s).

The 1927 annual report recorded that during the year £6,563 had been collected (compared with £5,985 in the previous year) with £4,800 paid over to the RUH and £1,031 to the cottage hospitals and other institutions.

However, this still amounted to over 22% of the Royal United Hospital’s income.

The economic recession caused receipts to fall back to £5,821 in 1928 and to £4,922 in 1929.

For the years 1930-32 receipts were just over £5,000.

But they started rising after 1932. Helped by funds raised for the new RUH, the figures for 1933 and 1934 indicated hope for the future.

So a promising start – RUH finances would have been in a poor state without the Box Scheme.

The opening of the new RUH at Combe Park in December 1932 pointed to likely increased running costs.

As the contributory scheme it had become, payments were made to other hospitals. Consequently, until 1934 (when it received £5,300), the RUH only got about £4,000 a year from the scheme.

Non RUH Payments 1934. This is illustrative – a far greater range of hospitals was covered over subsequent years.

- Almondsbury Memorial Hospital

- London Hospital

- Bath Ear Nose and Throat Hospital

- Paulton Memorial Hospital

- Bath Education Authority

- Freshford Cottage Hospital

- Bath Eye Infirmary

- Somerset County Council

- Bath Mineral Water Hospital

- St Mary’s Hospital

- Bristol General Hospital

- Wilts County Council

- Chippenham & District Hospital

- Victoria Hospital Frome

- Forbes Fraser Hospital

- Additional Benefits

FUND RAISING FOR THE NEW RUH

Cedric Chivers plans to raise funds for a new hospital at Combe Park began with £8,000 from donated Red Cross and St John’s funds left over from the war which could not be used for existing running costs.

In January 1930, Aubrey Bateman (who had succeeded Chivers as Mayor) sought to raise £100,000 (about £6.7m today) for a new hospital at Combe Park.

By May 1930 £51,603 had been raised. In November 1931 the Bath Council agreed to purchase the existing town centre premises for £30,000 to become a Technical College. Much of the balance came from Stanley Wills of the tobacco company. The new hospital opened December 1932.

AUBREY BATEMAN

From 1905 the Presidency of the RUH was always held by the incumbent Mayor of Bath.

But in 1931 there was a rule change and Aubrey Bateman remained (by election of the Board) President, whether or not he was Mayor. Bateman remained President until 1946. This reflected his role as fund-raiser which the existing mayor was happy to cede.

As a result of Aubrey Bateman’s fund-raising efforts the new hospital was able to open debt-free in December 1932.

Today this portrait of him still hangs in the old entrance of the RUH.

To my mind Bateman was one of Bath’s great mayors – on a par with Chivers.

Born in 1875, and like Chivers, he was 5 (but not 6) times Mayor – in 1929, 1934, 1940, 1941 and 1942. He came to Bath from Devon in 1923 and became a Bath Councillor in 1925.

Late 1945 he retired to Devon (nominally President of the RUH until 1946).

He was a man of independent means. In 1955 he left a large endowment to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge in memory of his wife who died 19 years before because “it was as a member of this college I met my wife to whom all my happiness in life is due”. 1933-4

THE SCHEME’S TURNING POINT

In January 1933 a new full-time scheme organiser, Mr Wilfred J Jenkins, was appointed to work at its new offices at Shepherds Hall, Princes Street, Queen Square.

In 1933 free hospital treatment was extended to include outpatients, and additional benefits included assistance towards dental treatment and dentures, convalescent homes, surgical appliances, glasses and ambulance.

In February 1933 Frank Pine stepped down as Chairman, but he remained very active as Vice-Chairman and, from 1934, as an RUH Board member.

Mr FG Hamilton, who was Chairman of the RUH Management Committee (1930-2, 1934-6 and 1942-5) took over as scheme Chairman.

This close link between the scheme and the hospital was reflected in the annual 120-page books of RUH hospital accounts published in the 1930s that contained the Box Scheme accounts at the back.

A new scheme quarterly magazine was published in 1934 (they only have a 1938 copy in the RUH library archives).

THE GOLDEN YEARS OF THE BOX SCHEME

The new full-time organiser, Wilfred Jenkins and his small full-time team in offices in Broad Street, Bath, encouraged a very substantial expansion in scheme revenues.

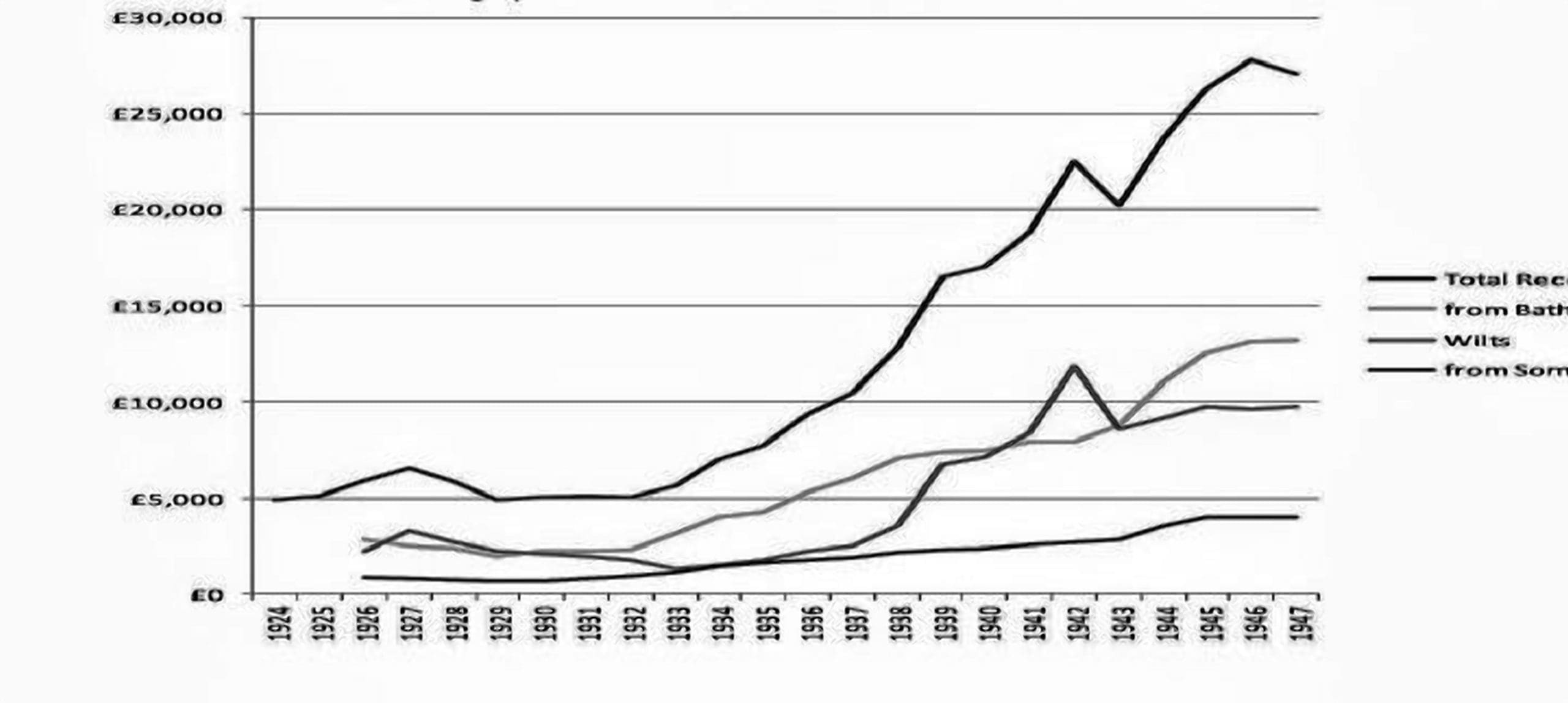

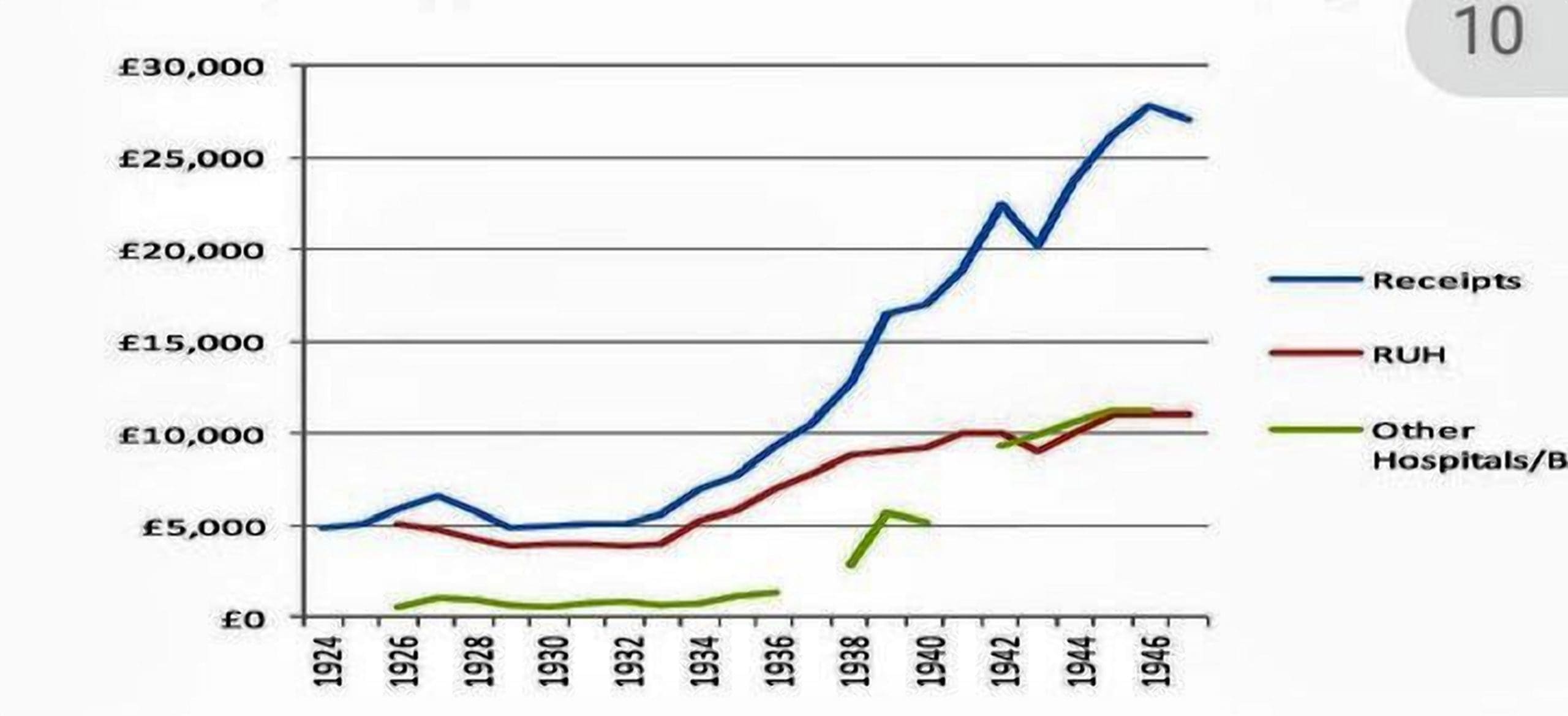

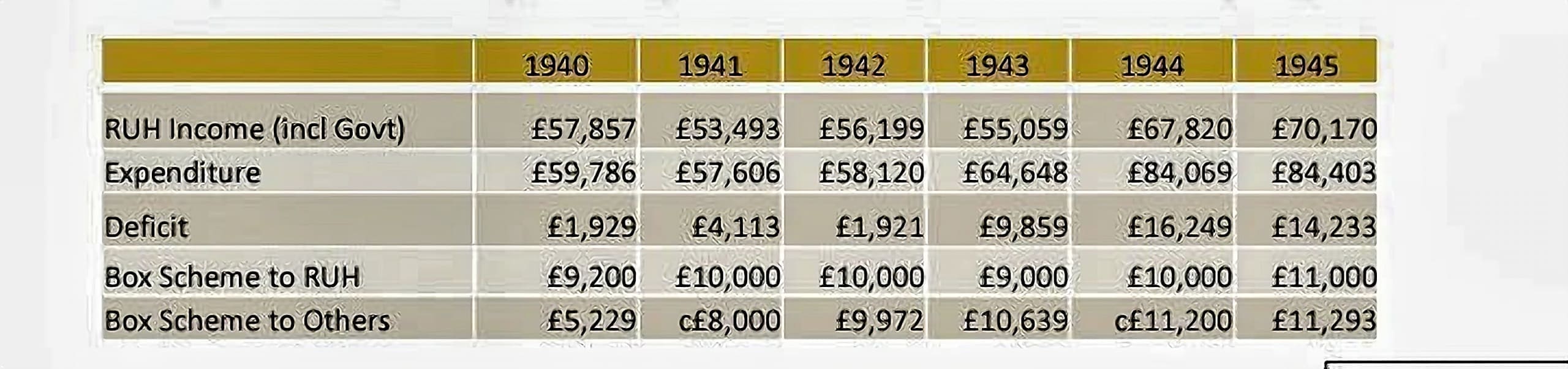

As a result, there was a fairly rapid rise in income from £5,636 in 1933 to £7,000 in 1934, to £10,489 in 1936, to £17,032 in 1940, to £23,724 in 1944, peaking at £27,791 in 1946.

As it can be seen from the graph income from Wiltshire was close to that received from Bath.

Payments to the RUH rose from £5,800 in 1935, to £7,000 in 1936, to around £9,000 in 1938-40 to £10,000 in 1941/2/4 (£9,000 in 1943), and to £11,000 in 1946.

However, scheme benefits had also changed to include outpatient’s treatments (probably to the chagrin of local GPs), dentistry, and optical and other appliances.

The sums paid to other hospitals, or for other benefits to scheme members, also rose from £713 in 1934, to £1,360 in 1936, to £5,229 in 1940, and to between £9,373 and £11,293 in 1942-46.

So, in 1943-1947, payments to other hospitals (and for benefits) exceeded payments to the RUH.

The data I have below misses out a couple of years for ‘Other’.

In terms of its overall finances, despite surpluses of income over expenditure for the period 1933-1936, the RUH found that from 1937 its operating deficits began to re-emerge. By 1943-1945 they exceeded the scheme’s payments to the hospital.

Of course, the impact of the war meant that there were considerably increased expenditures that were only partly off-set by inadequate government subventions. It must also be noted that the income mix of the hospital changed after the 1920s (when the only contributory schemes available before the Box Scheme were workplace schemes).

Other contributory schemes (like the HSA) also made payments to the RUH.

At its inception the Box Scheme accounted for 27% of the hospital’s income. This dropped to as low as 19% in 1927 and in 1928, and subsequently it was around 22% until it was back at 27% in 1936 and 1937.

Then in 1938-1942 it accounted for 30-33% of ordinary hospital income, dropping back in the late 1940s when income from other schemes matched that contributed by the Box Scheme. The sums raised by the Box Ssheme continued to rise during the war.

However, wartime resulted in an influx of people – servicemen and refugees from bombed areas.

This challenged the idea of a locally based scheme focussing on local voluntary hospitals. In 1946 the RUH faced a deficit of £52,401 to pass on to the NHS even though the Box Scheme had raised £11,000 for the hospital.

Nevertheless, the NHS was bequeathed a substantial dowry of investments by the RUH that more than covered these final deficits.

THE BATH SCHEME & THE HOSPITAL SAVING ASSOCIATION (HSA)

In March 1932 Chippenham Cottage Hospital and Freshford Nursing Home left the Box Scheme to set up their own scheme, but by 1933 they were part of the London-based Hospital Saving Association. I should note that the HSA was initially about saving Hospitals (not savings for its contributors).

Founded in 1923, the HSA grew to having over 2 million members in 14,000 local branches.

However, in 1938 the HSA withdrew to its London base, so Freshford rejoined the Box Scheme.

Some 9 other areas also came into association with the Box Scheme.

These included districts in Wiltshire (including Chippenham), Gloucester and Devon. The main Box Scheme was renamed ‘Bath Region Hospital Contributory Scheme’ and the association with the other schemes would be called ‘The Hospital Service Scheme’ and would be administered from the office of the Bath scheme.

THE BOX SCHEME AND THE PAYING PATIENTS SCHEME

The Box Scheme had an income limit of £6 a week for family subscribers, so the meant that many, more affluent, middle-class people were excluded from the Box Scheme.

The £6 a week limit was a fairly generous limit as it is about £690 a week (or £36,000 a year) now.

In 1924, to circumvent the RUH charter (to provide treatment free of charge for the poor), a separate RUH Hospital the Forbes Fraser had been built on the Combe Park site to house paying patients who could not afford nursing home fees. (However, in due course, the Voluntary Hospitals (Paying Patients) Act 1936 allowed voluntary hospitals to have pay beds.)

In September 1934 the Box Scheme office set out details of what was described as the Forbes Fraser Scheme. This was seen by the Bath Chronicle and Herald as a ‘Boon for the Middle Classes’.

A Guinea a year would provide for Forbes Fraser Hospital Treatment and would cover a whole family with no income limit. Broadly its terms were:

- Contributions: A guinea a year, extra 7s 6d for junior 16-21.

- Income Limit: None.

- Age limit: 60 to join

- Benefits: 3 guineas a week nursing for 4 weeks in any 12 months at any other approved hospital.

- Qualifications: No payment for doctors or for maternity or mental illness, accident cases covered by compensation, contagious or infectious diseases.

THE BOX SCHEME: PART OF A GREAT NATIONAL MOVEMENT

Contributory Schemes like the Bath Scheme and the HSA were part of a vast and growing national movement.

Its representative body, the British Hospital Contributory Schemes Association was formed in 1930.

On 29 September 1934 The Bath Chronicle reported on the AGM of the British Hospital Contributory Schemes Association at Bristol University. Some 94 schemes were affiliated with approximately 4 million members (including the RUH Bath Scheme).

The widespread rapid growth of British hospital contributory schemes was a significant feature of the inter-war years – with over 400 schemes and nearly 11 million members by the late 1930s.

The BHCSA covered a disparate membership with a variety of individual schemes as varied as its membership.

Ultimately the association was unable to find a coherent role for its members in a tax funded – free to use for all – NHS. (It would be interesting to see some research on the BHCSA – its membership and their schemes.)

It is not surprising that the officials charged with creating the NHS decided that there was no scope for bringing the diverse contributory schemes that had arisen across the country in the 1920s and 1930s, with their different benefits and objectives, into the funding and management of the new system.

In 1930s Bath the differentiation between the working-class scheme and the middle-class scheme for paying patients was contrary to the philosophical concept of the NHS.

Furthermore, whilst the better off could afford nursing home treatment, the very poor still used the former workhouse infirmaries – especially for childbirth. Local charity had also led to the founding of an excessive number of Cottage Hospitals by the late 1930s – some of which didn’t need saving by the NHS!

MUNICIPAL HOSPITALS

Neville Chamberlain’s Local Government Act of 1929 promoted a major reform of public medicine by transferring the Poor Law administration of the workhouses to the county and county boroughs, such as Bath.

This intentionally gave a great incentive to the local authorities with Workhouses to transform those Workhouse Infirmaries into Municipal Hospitals.

These accounted for around half of the country’s hospital beds.

Frome Road House Infirmary (having dropped the stigmatic name Workhouse in 1914) was a municipal hospital in all but name. But the Second World War transformed it into St Martin’s a fully fledged municipal general hospital.

In the late 1930s a number of Bath councillors thought it could be a basis of a municipal hospital service embracing the RUH.

But for many the independent voluntary hospital ethos was still valued. In the war the government insisted patients should treat Municipal or Voluntary hospitals alike.

So, Box Scheme members could be obliged to go to St Martins (where two of Frank Pine’s daughters, my aunts, did war work). 1940s

1940s RECORD BOX SCHEME PAYMENTS TO RUH

Despite the war the enthusiasm of Box Scheme workers was undimmed.

In the 1940s there were record Box Scheme payments to the RUH (and to other hospitals). But the RUH faced increased costs due to the war (despite significant government payments – and Aubrey Bateman pleaded for more).

Cumulative Deficits were by 1947 £52,401 (despite the sale of £35,000 of the investments valued at £363,331 in 1943).

Remaining liquid investments were now £86,308, but with land, buildings, furnishings re-valued at £242,020 a substantial dowry was passed to the NHS.

THE IMPACT OF ANOTHER WAR: THE NHS

The impact of War with refugees from bombed areas and admiralty and service personnel in Bath, also increased medical costs, meant that the local funding approach to hospitals made less sense.

The NHS absorbed both Municipal and Voluntary Hospitals (the latter with big dowries in investments).

It also spelt the end of most Contributory Schemes like the Box Scheme. Changes to National Insurance diminished the role of the Friendly Societies.

However, the NHS took over one of the best hospital services in the world.

Even so, the idealism that inspired those institutions should not be ignored.

My grandfather’s friendly society membership and his work on the scheme were inspired by his belief in The Brotherhood of Man.

Many in the Bath Friendly Societies Council of 1923 didn’t live to see the NHS and its impact on their philosophies.

That included my grandfather (FHP). He died on the eve of the Bath Blitz on 24 April 1942.

OVERVIEW

In one of the final issues of ‘Our Hospital’ Wilfred Jenkins (Organising Secretary of the Box Scheme) reflected, in a note on the history of the scheme:

“For the Committee and the many voluntary workers there was sadness in the knowledge that the scheme must end but no sense of failure. On the contrary, progress had been maintained throughout and the annual income was now larger than ever before.”

In the Bath Hospital Scheme the income had risen to nearly £27,000 a year and in addition the Hospital Service Scheme was producing more than £15,000 and the Paying Patients’ Scheme an annual income of nearly £3,000, so that altogether the Central Office was receiving some £45,000 a year for hospital purposes.

It was a great achievement and worthy of the enthusiasm and effort which had begun and sustained the work through a quarter of a century.” (£45,000 equates to over £2 million now).

Professor Martin Gorsky, who has kindly endorsed my book on the Bath Hospital Box Scheme, has commented on contributory schemes in ‘Mutualism and Health Care’ saying that: “It is surprising that there are relatively few references to the extent of these schemes in accounts of the development of health care in Britain.”

So did the Box Scheme save RUH? Yes, I would say it did – noting that it has since absorbed 7 other hospitals:

- Forbes Fraser,

- Orthopaedic

- Manor Hospital (on the Combe Park site)

- Ear Nose and Throat Hospital

- Bath Eye Infirmary

- St Martin’s general facilities

- Mineral Water Hospital! [But as Dr Martin Rowe (Chairman of History of Bath Research Group) has pointed out, it has saved itself from being taken over by Bristol hospitals!]

SOURCES This article is based on my book ‘Saving Our Hospital – The Royal United Hospital Bath and its Financing before the NHS – The Rise of the Box Scheme 1923 to 1948’ (2020).

Its Short title is ‘Saving Our Hospital: Bath’s Royal United’s Box Scheme’.

I am grateful to Professor of History, Martin Gorsky, Centre for History in Public Health, Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for his support for my project.

It reflects a range of sources used in my book notably:

- 335 newspaper articles from the weekly edition of the Bath Chronicle and Herald for 1900-1948 (often containing very detailed accounts);

- Statements and Annual Reports for the Bath Royal United Hospital for 1899-1945 from the RUH Academy Library (there are gaps in this collection);

- The Voluntary Hospital database based upon a secondary source ‘Burdett’s

Hospitals and Charities: - The Year book of Philanthropy and Hospital Annual’.

Other sources include

- Local History

David Beswick Lloyd: The Family Doctors in Newbridge 1900-2000 (Self Published 2007) - Kate Clarke: The Royal United Hospital 1747-1947 (Mushroom Publishing, Bath, 2001)

- George Campbell Gosling: The Patient Contract in Bristol’s Voluntary Hospitals, c.1918-1929 (University of Sussex Journal of Contemporary History, Volume 11, 2007)

- George Campbell Gosling: Co-operate Co-ordinate Unify The 1920 plan for Bristol Medical Charities (Southern History Society ‘

- A Review of the History of Southern England’ Volume 29, 2007)

George Campbell Gosling: - “Open the Other Eye”: Payment, Civic Duty and Hospital Contributory Schemes in Bristol,

c.1927-1948 (Medical History, 2010, Volume 54: pp 475-494) - C Coath-Wilson: A History of the Mayors of Bath (Charter Trustees of the City of Bath, 2006

- Roger Rolls: The Hospital of the Nation – The Story of Medicine and the Mineral Water Hospital Bath (BIRD Publications 1988)

- The Bath Post Office Directory 1932

- Materials from the RUH Academy Library archive. Materials from the Bath Record Office archive.

- National History

Brian Abel-Smith: The Hospitals 1800-1948 (Heinemann 1964)

George Campbell Gosling: Payment and Philanthropy in British Healthcare 1919-1948 (Manchester University Press 2017) - Victoria Solt Dennis: Discovering Friendly and Fraternal Societies (Shire 2005)

- Martin Gorsky: Local Government Health Services in Interwar England: Problems of Quantification and Interpretation (Article in Bulletin of the History of Medicine · October 2011)

Martin Gorsky & John Mohan with Tim Willis: Mutualism and health care (Manchester University Press 2006) - Alysa Levine, Martin Powell and John Stewart: The Development of Municipal Hospitals in the English county Boroughs in the 1930s (Cambridge Journal for the History of Medicine January 2006)

- Noel Whiteside: ‘Social protection in Britain 1900-1950 and welfare state development: the case of health insurance’

(University of Warwick, UK. 2009). - On-line sources including:

- Forever Friends Appeal for the RUH and ‘Help Us Give Support’ to the RUH (accessed March 2019) see:

https://www.foreverfriendsappeal.co.uk/ - Wikipedia ‘Private Hospitals’ (accessed March 2019) see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Private_hospitals_in_the_United_Kingdom Elite Hospital List (accessed March 2019) see: https://www.freedomhealthinsurance.co.uk/downloads/elite/hospital-list

- Friendly Societies History (http://www.friendlysocieties.co.uk/history.htm)

- The voluntary hospitals in history (http://www.hospitalsdatabase.lshtm.ac.uk/the-voluntary-hospitals-in-history.php) ‘From welfare state to welfare society’ 27 December 2012, Barry Knight (http://www.fabians.org.uk/from-welfare- state-to-welfare-society)

HISTORY OF BATH RESEARCH GROUP

The preceding article is an abstract of a PowerPoint talk that I gave online to the History of Bath Research Group at their Zoom meeting on Monday 8 March 2021.

As I said at the outcome of my talk although I now live in Sutton, Surrey, I was a Bathonian born and bred and my father was in charge of the Orthopaedic Workshop at the RUH into the 1970s.

A copy of my talk to view or download is at https://historyofbath.org/Recordings/Recordings.

The article was submitted to the group for publication as part of their Annual Proceedings.

Following the Zoom presentation I was pleased to receive a hand-written letter from Dr Michael Rowe, Chairman of the History of Bath Research Group dated Monday 15 March – a week after my talk.

As, before his retirement, he was an RUH and St Martin’s doctor for a large part of his career I was anxious that my story might not have been new to him. However that proved not to be the case – I was covering fresh ground for the Group.

In his letter he said:

“Dear John,

Thank you so much for such a fine lecture on the RUH. This is an original and comprehensive piece of research which is the core of the History of Bath Research Group.

In this age when the NHS hospitals are there for all to use, so many people know nothing of the fight to obtain and retain their priceless resources. To hear about the Box Scheme from a member of the family that drove it through at a critical time was a rare privilege.

Many people have reason to be grateful to your grandfather and I am so pleased that your work will be published to a wider audience, and as a memorial to those involved.

With Very Best Wishes and Thanks,

Michael”

Shortly before giving this talk, I became a member of the History of Bath Research Group. They had already, for at least a year, listed my book on the humble Chelsea Road area of Bath (in which I grew up) on their website which I published early 2019. Unlike much of what I have produced, it is quite readable and over 250 copies have been printed and sold.