De Montalt House

De Montalt House is just off Summer Lane with its wonderful and special views and vistas to the South.

De Montalt House was, apparently, built about 1848 and one of the first occupiers was a Col Mee.

I have not been able to establish exactly who he was, but he sued his landlord for not providing the water that he had said he would.

By 1861 Maj John Sutton (1810 – 1891) and his wife Mary Ogden Evans (1812 – 1914) occupied the house.

He was the son of Rear Admiral Samuel Sutton (1760 – 1832) and his wife Charlotte Ives (1780 – 1852).

Admiral Sutton had served with Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronté KB (1758 – 1805) at the Battle of Copenhagen and also commanded HMS Victory from 1803 – 1804.

Alfred Samuel Goodridge (1827 – 1915) and his wife Catherine Gertrude Gray (1843 – 1922) occupied De Montalt by 1871.

He was the third son of Henry Edmund Goodridge (1797 – 1864) the famous Bath architect, and his wife Matilda Yockney (1798 – 1876).

H E Goodridge designed, inter-alia:

- Beckford’s Tower (1827)

- The Corridor (1824)

- Cleveland Bridge (1827)

- Holy Trinity church (1832 – 1835)

Alfred Samuel became an architect as well and laid out Smallcombe Vale Cemetery and designed the mortuary chapel there.

By 1881 John Hector Whitaker (1821 – 1899) and his wife Mary Ann Gee (1823 – 1890) were in residence.

He was a cabinet maker working out of De Montalt Mill.

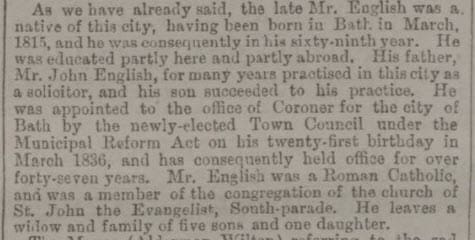

By 1889 William Joseph English (1855 – 1890) and his wife Emma Louisa M Egerton (1853 – 1944) were at De Montalt House.

He, like his father before him, was Coroner of Bath. His father, Alban Huddleston English (1815 – 1883), had only died in 1883 and William Joseph was only 35 when he followed him just six years later.

After his death, De Montalt was offered for rent at £70 p.a. At today’s value that’s about £30,890.00 p.a or £2,574 per month.

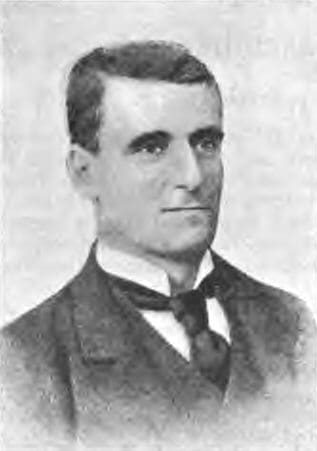

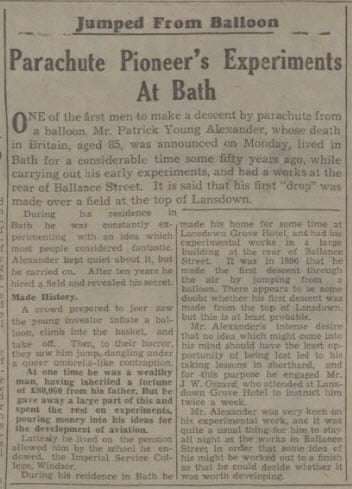

By 1891 Patrick Young Alexander (1867 – 1943) lived at De Montalt House.

He was a British aeronautical pioneer fascinated by the prospect of heavier than air flight, an enthusiastic balloonist and meteorologist.

His father was Andrew Alexander (1828 – 1890), a civil engineer interested in aeronautics and a founder member of the Aeronautical Society in 1866 and told told Patrick he was sure that the problems of heavier than air flight would be solved.

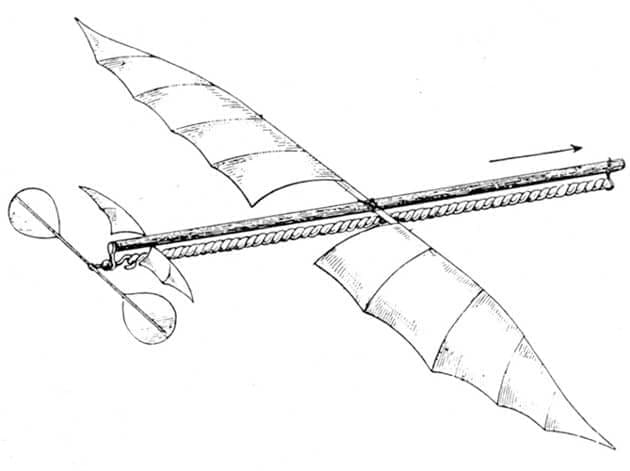

In 1878, Patrick Alexander built an elastic driven model aeroplane as designed by Alphonse Pénaud (1850-1880), the Planophore, a model airplane was capable of achieving flights over a distance of 60 metres.

It was a monoplane fitted with a stabilizing tail section.

The rubber band motor drove either a tractor, or a pushing type propeller, depending on the model type.

The characteristics of Pénaud’s machines, would remain for a long time those of future airplanes, and were truly advanced for the era.

In the 1880s his family moved to Bath.

On 1 April 1885, 3 days after his 18th birthday, Patrick Alexander signed as an apprentice Merchant Navy officer.

The very next day he sailed upon the Minero, a barque of 478 tonnes bound for Fremantle in Western Australia, a distance of 12,500 miles. 60 days into the journey, while aloft helping with the sails, Patrick lost his grip fell and broke his leg.

The ship was still three weeks away from port and he was strapped into a bunk for the rest of the journey. After arriving in Fremantle, Minero set sail for Cossack and Port Walcott some 1,000 miles to the North, seeking a cargo.

In rough weather fell and broke his injured leg again. Minero returned to London without him and his injuries left him lame for life. During this period his elder brother and his mother died in Bath.

In 1890 his father died leaving him £58,670 16s 4d equivalent to £43,850,000.00{1] now.

He was independent and became interested in meteorology, parachutes, balloons, propellers and wireless telegraphy.

On 9 June 1891, Patrick Alexander made a gas balloon ascent in the company of aeronaut Griffith Brewer (1867 – 1948), this was the first of a number of balloon ascents that would lead to his becoming a licenced balloonist.

He was close friends with Wilbur (1871 – 1948) and Orville ()1867 – 1912) Wright, Louis Bleriot (1872 – 1936), Ferdinand von Zeppelin (1838 – 1917), Charles Stewart Rolls (1877 – 1910) of Rolls-Royce and Lt Gen Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, OM GCMG GCVO KCB DL (1857 – 1941).

At Christmas 1902 he visited the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk but later missed a crucial telegram and, thus, missed the opportunity to witness the first flights of the Wright Flyer on 17 December 1903.

In June 1904 American aviation pioneer Samuel Franklin Cody (1867 – 1913) came to Aldershot to test his kites. There, in collaboration with the Army, he worked on balloons, kites and aeroplanes.

Patrick Alexander moved to nearby Mytchett in Surrey where he was involved with the Army School of Ballooning. He shared a house with Cody who later went on to become the first man in England to fly an aeroplane.

In 1910, Patrick Alexander created the Alexander Award, with a £1,000 prize (about £361,100.00 now[1]) for the development of a lightweight engine suitable for aviation. The Green Engine made by Aster Engineering won.

In WWI, Patrick Alexander went to America where he aided British propaganda by making statements in the American press. He was well known to New York journalists who reported his views at length and naturally Patrick expressed his view on the importance of aviation in the conflict. In 1917 he was given a job by the newly formed Air Ministry at the Meteorological Office at Falmouth; here he worked until the end of the war.

He had spent all his inheritance and so taught at life at the Imperial Service College, Windsor.

He is not well known; having failed to make any singular, lasting contribution to aviation but he disseminated ideas and gave generous donations. He died with only £168 15s 6d – equal to about £24,200.00[1] now – to his name.

By 1900 Col Robert Hawthorn (1833 – 1900) and his wife Amelia Enderby Dow (1843 – 1908) lived at De Montalt. He was a colonel in the Royal Engineers, she was the daughter of a Royal Navy Commander.

By 1911 Carew Elwell (1852 – 1926), the widow of Dr Alfred De Courcy Lyons (1852 – 1897) was occupant.

Carew Elwell was the daughter of Edward Elwell (1816 – 1857) and Georgiana Ash (1822 – 1886) and the grand daughter of Edward Elwell (1783 – 1869) and Carew Spurrier (1791 – 1871).

In 1817 Elwell took over the Wednesbury Forge – which had existed since the reign of Elizabeth I – and quickly built a reputation for quality edge tools. By 1851 management of the business had passed into the hands of Edward’s son, who, unfortunately died prematurely and so his father resumed control of the business until his death in 1869 when Alfred Elwell, Carew’s sister, took over the running of the business.

The History, Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire, William White, Sheffield, 1851 says:

"Mr Elwell, of Wednesbury Forge Works, employs about 300 hands, and machinery, propelled by water and steam power, in the manufacture of spades, shovels, hoes, axes, and other edge tools, for the home and foreign markets”.

Carew Elwell married Dr Alfred De Courcy Lyons (1852 – 1897), the son of Rev John Lyons (1804 – 1883) and Susannah Watson (1820 – 1906). He qualified as a doctor at Aberdeen University then commissioned into the 1st Gloucester Engineer Corps and later became a GP in Yatton.

By 1915 Algernon Charles Milsom (1883 – 1964) and his wife Adeline Mary Vowles (1890 – 1979) occupied De Montalt[2].

He was the son of Francis Henry Milsom (1855 – 1937) and Agnes Mary Cocks (1859 – 1889), the grandson of Charles Milsom (1825 – 1892) and Sarah Frances Tulley (1826 – 1879) and the great grandson of Charles Milsom (1800 – 1880) and Hannah Cole (1791 – 1865).

It was his great grandfather Charles Milsom (1800 – 1880) who founded C Milson & Son in 1825 which was taken over by Duck, Son and Pinker in 1921. Duck, Son, and Pinker opened in 1848 and both businesses traded until 2011.

Algernon Charles eventually became chairman of the company[3].

From 1932[4] to 1939 Frank Steer Norton (1885 – 1965) and his wife Margaret Sophia Lock (1891 – 1989) occupied De Montalt.

In 1939 Constantine Warren Maude Moorsom (1873-1955) and the widow, Nesta Theodora Bellingham Bailey (1900-1974), of his cousin Edgar Robert Henry Moorsom (1864-1932) were living at the house.

Constantine’s daughter Ruth Maude Moorsom (1905-1994) married Anthony Leonard Winstone Scott (1911-2000) a son of Ernestine Hester Maud Bowes Lyon (1891-1981) a cousin of Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes Lyon (1900-2002), perhaps better known as Queen Elizabeth, the queen mother.

Quarry Vale

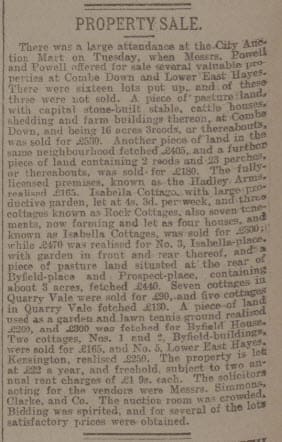

Quarry Bottom / Rise / Vale was built after 1805 and probably sometime between about 1810 and 1825 as we know from “Old John Greenway’s” account what Combe Down was like before that.

However, when I came to do Quarry Bottom / Rise / Vale I approached it with something of a sinking feeling.

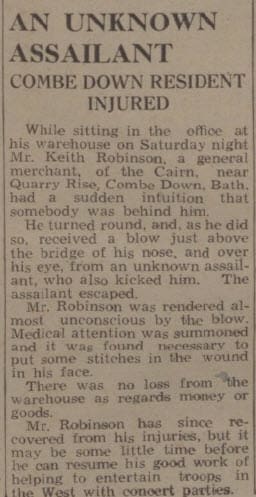

I knew it would be difficult to find published information about the inhabitants for they were working class people – not middle class or higher and the ‘social medium’ of the day, the newspaper, did not really follow their world unless criminality or scandal was involved. This gives a distorted image of working people’s lives.

I could, of course have concentrated on family trees, but this is a great deal of work for well over 100 families about whom I know nothing and it seemed unlikely to turn up anything very interesting for this site, except, perhaps. to a member of that family.

So I decided to take a look at the census, give a flavour of the range of occupations, pick out a few that were well represented and give a thumbnail sketch of those, as well as try to find some news clippings.

The table below gives occupations from the censuses and I decided to thumbnail agricultural labourer, laundress and quarryman.

| 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881* | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | |

| Agricultural labourer | 9 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Baker | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Blacksmith | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Bricklayer | 1 | |||||||

| Building labourer | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Butcher | 1 | |||||||

| Butcher’s assistant | 1 | |||||||

| Carpenter | 1 | |||||||

| Carter | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Chair maker | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Charwoman | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Coachman | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Coal deliveryman | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Corset machinist | 1 | |||||||

| Dairyman | 1 | |||||||

| Domestic servant | 2 | 4 | 1 | |||||

| Dressmaker | 1 | |||||||

| Engine driver | 1 | |||||||

| Errand boy | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Fireman | 1 | |||||||

| Fuller’s earth miner | 1 | |||||||

| Gardening | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gasfitter | 1 | |||||||

| General labourer | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Home decorator | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| House painter | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Hurdle maker | 1 | |||||||

| Laundress | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 5 |

| Lodging house keeper | 1 | |||||||

| Maltster | 1 | |||||||

| Mason’s labourer | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Midwife | 1 | |||||||

| Milkman | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| No occupation | 2 | |||||||

| Nurse | 1 | |||||||

| Own means | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Page boy | 1 | |||||||

| Painter | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Parish relief | 1 | |||||||

| Pauper | 1 | |||||||

| Plasterer & slater | 1 | |||||||

| Quarryman | 20 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |

| Railway labourer | 1 | |||||||

| Schoolmaster | 1 | |||||||

| Seller of tobacco | 1 | |||||||

| Shoemaker | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Stoker | 1 | |||||||

| Stone mason | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 38 | 25 | 26 | 34 | 17* | 38 | 30 | 35 |

* 3 houses uninhabited

Agricultural labourers

Before enclosure agricultural labourers were either farm servants, hired at a hiring fair for some considerable period, receiving a large part of their wages in kind, or day labourers, who found themselves in relatively comfortable circumstances.

Many had their own holdings and could also draw an income from the commons. They produced many of their implements themselves. Even in winter a labourer found employment in the woods and barns. Wages were low, but when working for a farmer, the men were well fed by him.

However with enclosure common land was gradually taken over by single landowners who rented the land out to tenant farmers, who in turn hired casual labourers to work for them – all because it was ‘economic’.

Agricultural labourers with families and no specialised skills were hired on a casual basis for specific tasks.

They would be paid for the work they did and received nothing if they were sick or if the weather was too bad for them to work. Wages were low and unemployment high.

Many agricultural labourers had to depend on poor relief to help them through the difficult times, but even this couldn’t be relied upon after the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834.

Before 1834 poor relief was dealt with at parish level. Labourers could ask for outdoor relief to supplement their loss of wages due to illness or unemployment.

It was up to the parish overseers to decide who was eligible for help, and as they often knew the recipients, it could be a fair system.

By the 1830s the attitude of the elite had changed.

Being poor was now ‘your fault’ and poor relief was believed to encourage people to ask for help rather than work harder.

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 was a way to reduce outdoor relief and make the workhouse the only way of accessing help. The poor were seen as idle, unskilled and unintelligent.

But the range of farm work that these ‘unskilled’ people did shows just how wrong that was.

Labourers would sow seed and tend to crops. They would care for the farm animals: milk cows, feed pigs, herd and shear sheep and look after poultry. They layed hedges and maintained farm buildings, fences, gates, tracks, ditches and ponds. In the summer they did the harvesting. Their wives and children would be employed to rake the crop and tie it into sheaves. Winter work included threshing and sieving to separate the grain and chaff. The introduction of threshing machines took away valuable winter work from the labourers and made matters worse.

A table appears at the end of a pamphlet called a “A View of Low Moral and Physical Condition of the Agricultural Labourer” published in Blandford in 1844.

It shows the earnings and expenditure for 49 weeks of the year in 1843 of a farm labourer, his wife and four children. What with contributions to the clothing club, the benefit club and schooling as well as payment for food, fuel and shoe leather, they had just enough to keep their heads above water financially and had no money left for luxuries apart from a few currants. The title speaks for itself and the author, the Rev Lord Sydney Godolphin Osbourne (1808 – 1889) became better known for his work in championing the cause of the agricultural labourer in the south of England.

Sir James Caird (1816 – 1892) reviewing the state of the English agriculture for The Times in 1850, quoted that the labourers diet on south Salisbury Plains consisted of bread with a little butter or lard, and cheese and bacon only occasionally if you could afford them.

Jacob Baker of Hodson near Wilton in Wiltshire said in February 1850:

"And you, gentlemen, must know that our case is very bad and that we have not near victuals enough. How would you like to sit down with your wife and young children four days in a week to not half bread and potatoes enough and the other three days uponnot half enough boiled swedes and but with little fire to cook them with?"

The workhouse was the only place to go if you came to the end of your resources; there was no welfare state and no suffrage for the working man.

The rates an agricultural labourer was paid in the early 19th century have been given as:

Day labourer 10d per day with beer in winter Carrying hay 1s per day with board Harvesting 30s per month with board Reaping 2s 6d per acre Mowing 8d to 1s per acre Threshing 1s to 2s 8d. per quarter

In 1874 the following budget was given for a farm labourer, his wife and three children and excludes clothing, entertainment or any extras:

| Prices in shillings (s) and pence (d) | s | d | 2016 equivalent | |

| Weekly income | 13 | 111/2 | £341.30 | £17,747.60 |

| Weekly expenditure without clothing | ||||

| 5 gallons bread | 6 | 3 | ||

| 1/2 lb butter | 8 | |||

| 1 lb cheese | 6 | |||

| 1 lb bacon | 8 | |||

| 1/2 lb sugar | 2 | |||

| Pepper, salt, etc. | 1 | |||

| 2 oz tea | 4 | |||

| 1/2 lb candles | 31/2 | |||

| Soap | 2 | |||

| Soda, starch, etc | 1 | |||

| Coals | 2 | |||

| 1 faggot | 21/2 | |||

| Rent and rates | 1 | 6 | ||

| Sick club | 6 | |||

| Boots | 7 | |||

| Children’s schooling | 3 | |||

| 12 | 5 | £303.60 | £15,839.20 | |

| ‘Free’ income | 1 | 61/2 | £37.70 | £1,908.40 |

The average weekly wage in 1850 was 9s 31/2d (£350.40 or £18,220.80 p.a.) but effectively falling to 14s (£332.80 or £17,305.60 p.a.) by 1875 and by 1900 it was only 14s 10d (£279.60 or £14,539.20).[5]

Laundress

Quarry Vale laundresses worked at home converting the house to a ‘factory’ for part of the week – as you will see laundering clothes was not easy, which is why it was sent out by all who could afford it.

Since the basic equipment was easy to acquire, it was often done by widows and married women with a low household income.

Sometimes their husband’s work was seasonal, such as the stone mason, quarryman or labourer.

Sometimes unemployment, illness, injury, drunkenness or irresponsibility meant her husband didn’t support the family.

Washing combined quite well with family life even though it meant taking on the hard work of laundry. But they had to take care, clothes were expensive and damage to a customer’s laundry just could not be considered.

A laundress did not just wash and dry. She might have to make repairs, patch clothes and sew buttons.

Then she would treat the stains. Paraffin wax, alcohol, lemon juice or even urine were used.

She would have to fetch water from the well and soak the clothes for hours to loosen stains.

Then the clothes would be put in heated water and heating water was a major task in itself. Soap the laundress had made herself was added possibly made from caustic soda and a fat such as lard or oil such as hemp oil.

Then she would rub each item against a washboard and use a dolly then rinse and wring the clothes with a wooden or iron mangle.

Next, a laundress boiled the clothes to kill lice and other vermin after which they were removed from the boiling water with a laundry stick and rinsed several times in hot water.

They were allowed to cool and then rinsed again in cool water, that may have been starched to help to prevent wrinkling and ease ironing.

Next they were dried and ironed with flat irons heated on the range. Finally clothes were aired to ensure they were completely dry and free from mildew.

All of this took time. Working 60 to 80 hours a week was not uncommon but the earnings, though piecework, could make a substantial change to a family budget.

In about 1880 earnings of 1s to 1s 6d a day could be made that’s 5s to 7s 6d weekly or about £13 to £19 10s a year. in today’s terms that’s about £114.50 to £171.80 a week or £5,954 to £8,933.60 p.a.[6]

Quarryman or quarry labourer

Quarrying is difficult work, but the quarryman is assisted by nature. Combe Down stone is a freestone that can be sawn or squared up in any direction.

Underground stone, like that of The Firs, was extracted by the room and pillar method with slots cut into the rock face horizontally and vertically, the height being determined by the distance between bedding planes and, on Combe Down, there were, generally, three beds, with a total thickness of about seven feet.

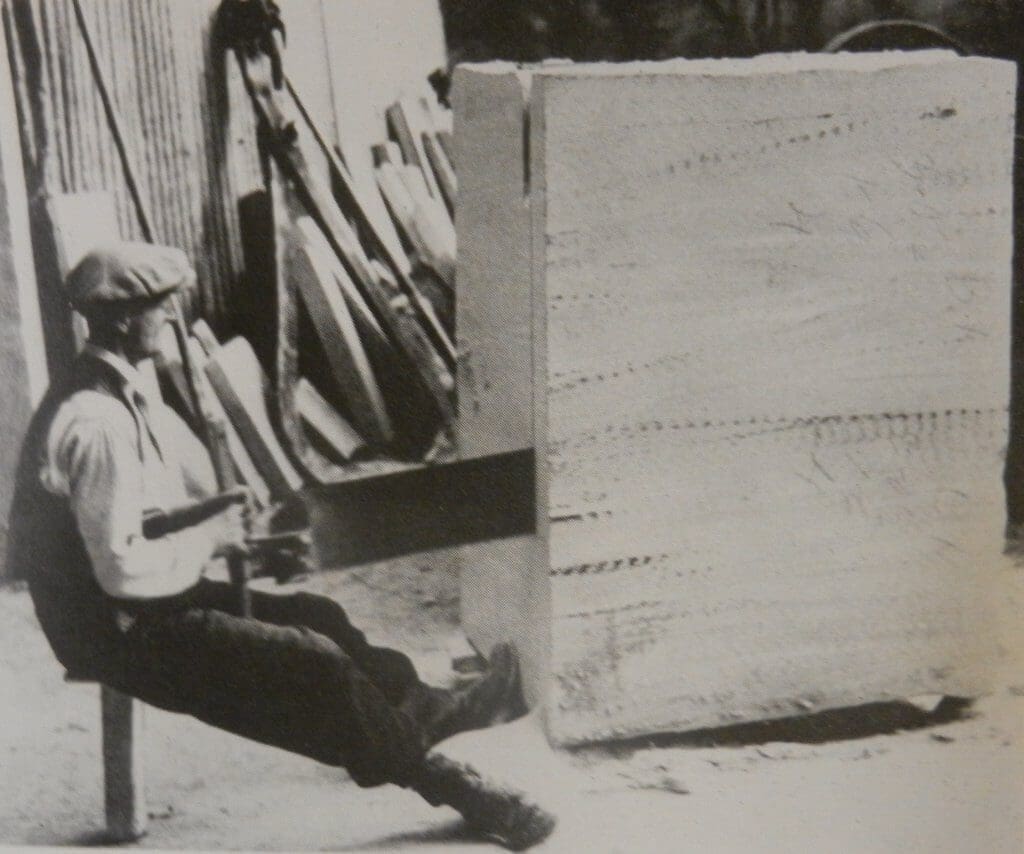

All the work of cutting the stone was done by hand.

An area to be quarried was marked out at the face then a picker would use a pick to create a picking bed by removing the top six inches of stone above the block to be extracted. With a shallow razzer saw cuts were made until larger frigbob saws could be inserted to continue the downcut.

Frigbobs were up to eight feet in length and were lubricated by water from a drip tin – a tin with a hole in the side with dripping water to lubricate the saw cut. Pillar saw cuts also show that one man, rigid blade saws up to 7 feet long, were used in addition to splitting with wedges and chips. The cuts next to a support pillar had to be finished without stopping the saw or pressure from the pillar would break the blocks or jam the saw.

A central sub block, called the wrist, would then be sawn with narrower cuts at the back to prevent jamming when it was plugged and feathered to lift it up and break it off between the beds. Then it was removed and cuts along the back of the remaining sub blocks would be made so that they, too, could be broken from their beds by the plug and feathers. Sawing was slow and back breaking work. It took about an hour to saw down a foot over a length of five feet and it was done in poor light.

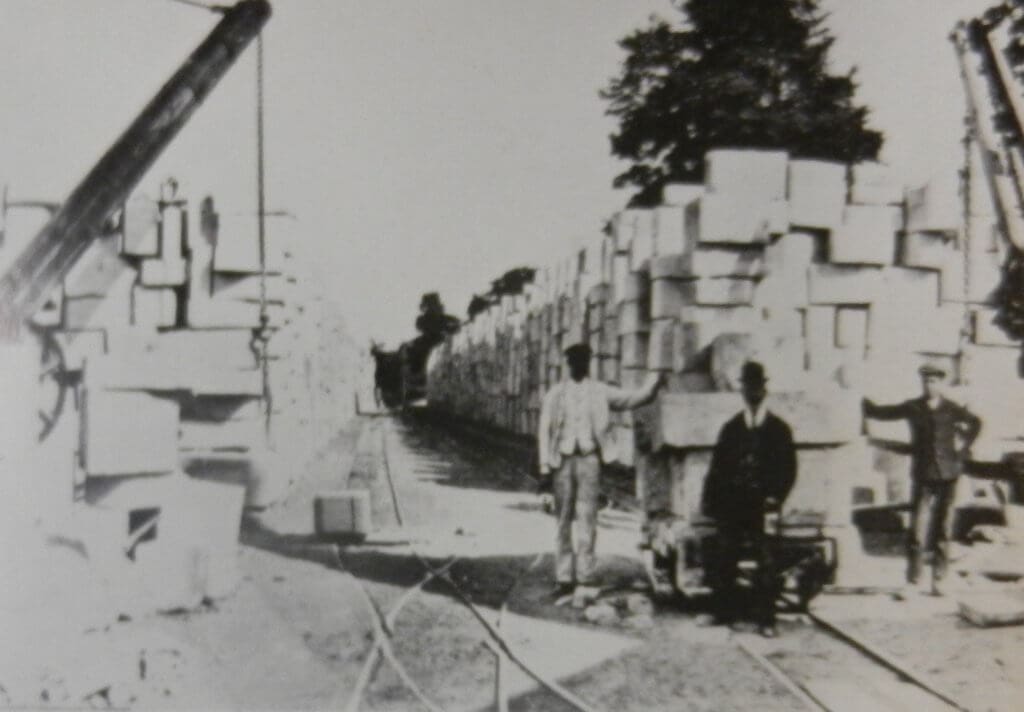

Once cut each block was removed by chains or a Lewis bolt using a crane and then checked for faults as only perfect blocks could be sold.

Blocks were trimmed to about 3 x 2 x 1 metres underground and moved along a cart road to the stacking area. The trimmings were used for backfill.

Frame saws, with a shallow blade, were used to cut up quarried blocks into products such as ashlar and copings.

Only trimmed blocks were hauled up to the surface on the inclined horse drawn tramway. The horses moved the blocks of cut stone from the working face to the stacking ground.

Outside there was a windlass on a mound where a horse was coupled to a long arm and go round winding the rock up the hillside until it got to the flat where there was a shed.

The stone was wet and so had to be laid out to dry, and if it was laid in the wrong direction, it crumbled away. As it was pulled out, each stone was marked on the leading face with a black mark, and that was the way it had to be placed to dry, which could take six months.

Lighting underground was a candle, oil lamp or carbide lamp placed in a ledge cut into the wall. At intervals a ventilation shaft, called a light hole, was dug to the surface. Horses spent much of their lives underground being stabled underground during the week only going to the fields at the weekend.

Wages were low. A report in 1891 said about stone quarries:

"This is an industry in which the men work very irregularly mainly owing the weather, and deductions for lost time to be made from the wages for a full ordinary week as given in the detailed tables, are larger than for any trade yet dealt with, the figure being not less than 21 per cent."

The same report gave the average wage for the South Western district of England (Wilts, Devon and Somerset) as £44 p.a. which is about £19,410.00 in today’s terms.[7]