Combe Down

Combe Down

In ‘Rambles about Bath’, Tunstall says about Monkton Combe:

“In 1780, it paid £103 poor rates, its population being 280; in 1841, from the great increase of the village of Combe Down, its population was 1,107. This is steadily increasing.”

In 1831 Samuel Lewis put the population of “Combe (Moncton)” at 855.[1] Looking at the census allows us to chart the population growth.

Properties & Population on Combe Down 1841 to 1901 from census reports (see Census summaries)

| 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | |

| Properties | 294 | 339 | 375 | 421 | 444 | 554 | 527 |

| Males | 758 | 829 | 803 | 886 | 955 | 1,192 | 1,186 |

| Females | 862 | 909 | 959 | 1,059 | 1,120 | 1,375 | 1,256 |

| Total population | 1,600 | 1,738 | 1,762 | 1,945 | 2,075 | 2,567 | 2,372 |

It’s clear that the rate of growth was fastest before 1840 and then steady.

Unfortunately, the census boundaries for each enumeration district change census by census and so whilst it is theoretically possible to look at Monkton Combe village, Combe Down Village and the areas on Greendown separately, to do it with any real accuracy would be a major task.

By 1850, the stone quarries, the reason for Ralph Allen to establish Combe Down village in the first place, were in decline[2] with the quarries having been fairly well worked.

Meanwhile vast quantities of good quality Bath stone had been discovered at Box when Brunel built the Great Western Railway.

This stone was also, of course, right beside the new railway, making transport simple. In these new quarries the total quarried area is approximately 2 miles long and a mile wide and has some 15 miles or more of tunnels.[3]

Roman Villa

Roman Villa

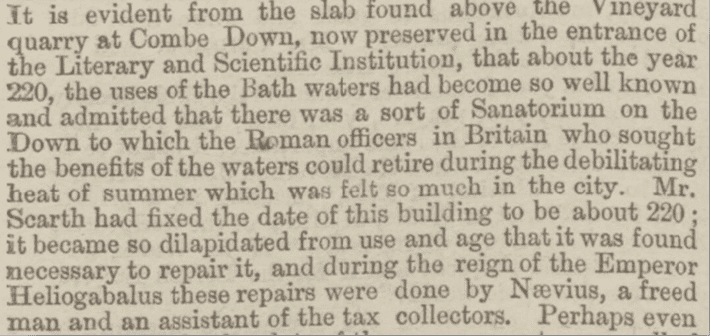

1852 saw the discovery of Roman remains on Combe Down. In 1822 Henry Mingden Scarth wrote:

“Two Stone Coffins were found near Burnt House Turnpike Gate (in the line of the Foss Road), and previously to this two others near Claremont Place, Combe Down.[4] ……It was discovered while making a garden to a new villa, and served as the covering stone for the lower part of a Stone Coffin, in which was a perfect skeleton. This spot has since proved to have been the site of a Roman villa, and many objects of interest which have been discovered there, are carefully preserved by the owner. Five Stone Coffins have been found on the spot, besides urns containing burnt bones, and a stone box containing the head of a Horse. The Inscription, which is not deeply cut, is difficult to read, owing to the decomposition of the stone. It is as follows: ‘For the safety of the Emp. Cms. Marcus Aurelius, Antoninus, the pious, fortunate, invincible Augustus, Naevius Freedman of the Emperor, and assistant of the procurators, restored the chief military quarters which had fallen to ruin’."[5]

The words “while making a garden to a new villa” indicate Belmont House as the likely site as it was being constructed at this time, which is reinforced by the article in the Chronicle. In 1867 it was felt that the villa may have been a ‘Sanatorium’:

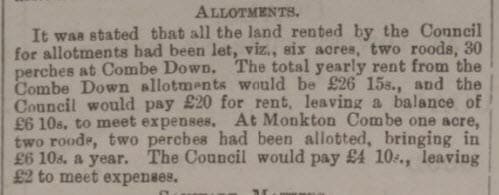

Allotments

Allotments

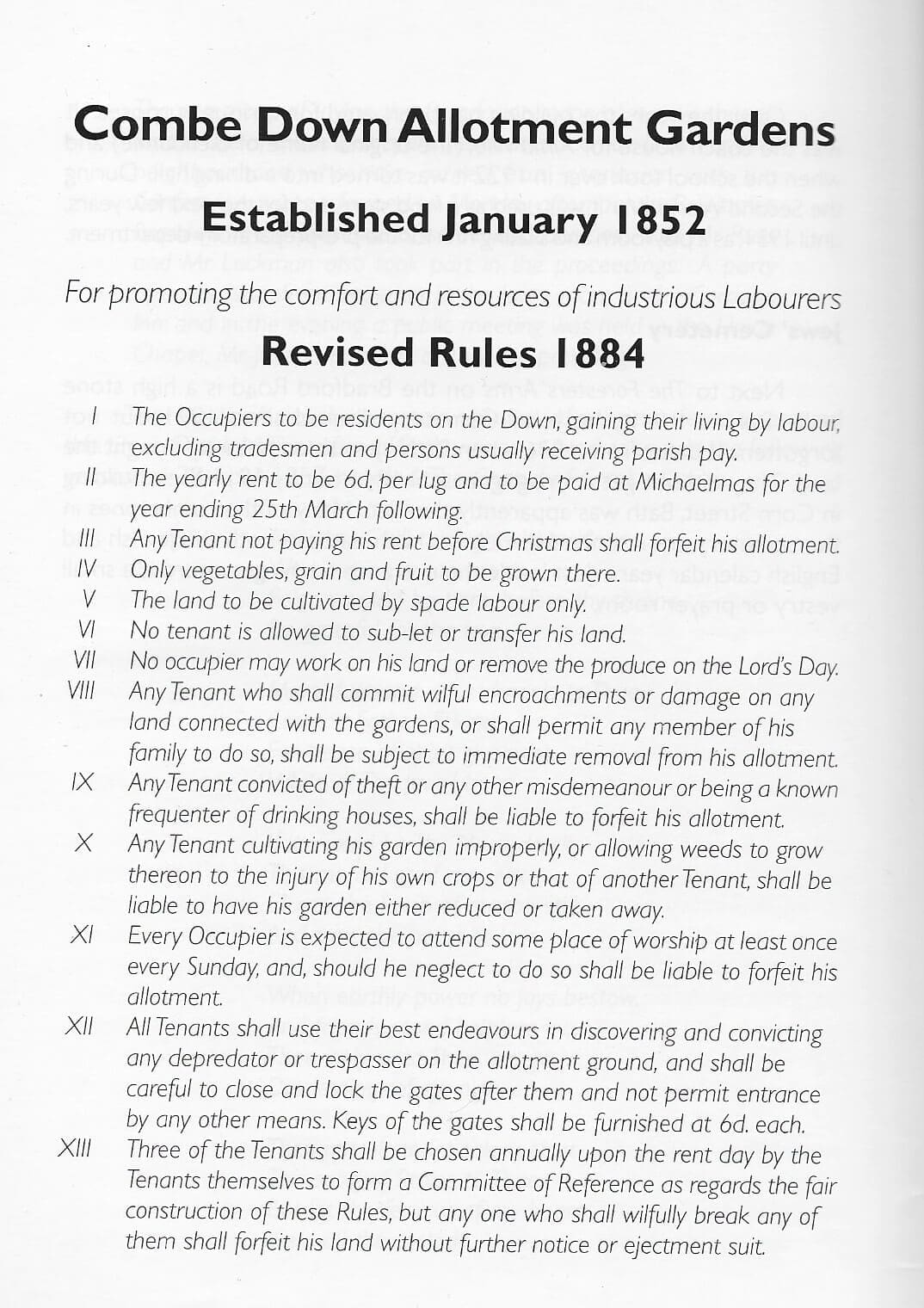

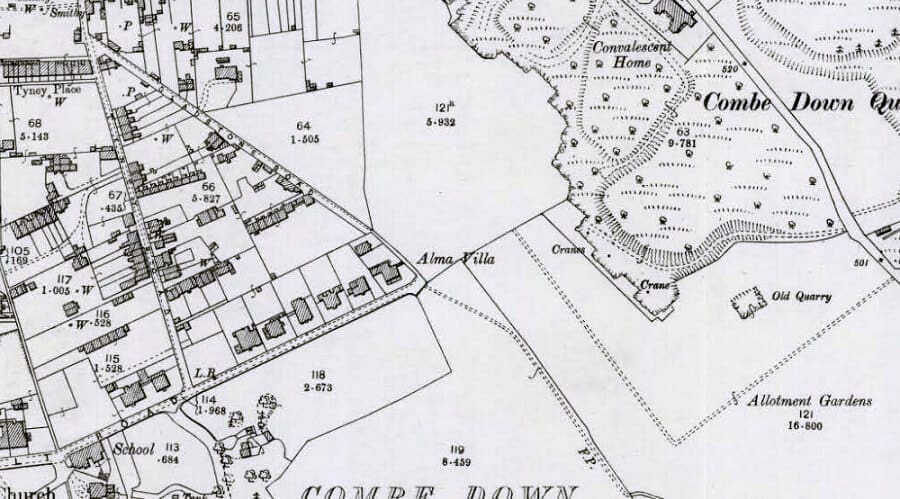

Allotments on Combe Down were introduced by Rev G W Newnham in 1852.

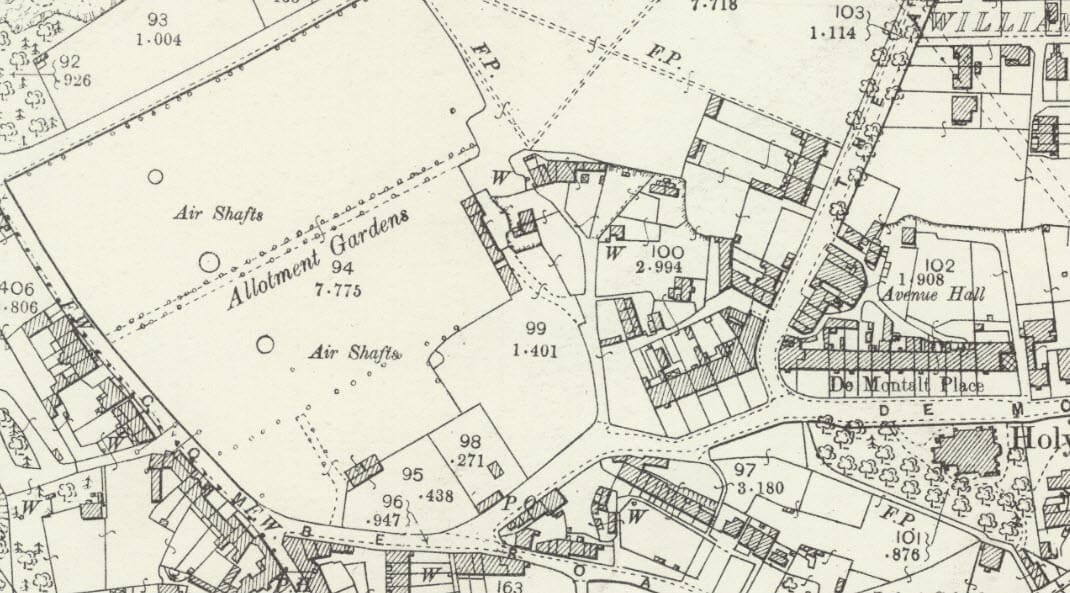

The allotments were in the area bounded by North Road and Combe Road as shown on the map.

This is the area to the South of Westerleigh Road, above Combe Road Close and to the West of Rock Lane. There were some 40 – 50 allotments of about 1/8 of an acre and the rules from 1884 were published in Around Combe Down by Peter Addison.

There were allotments in the Westerleigh Road area until 1938 when there was a story in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, Saturday 8 October 1938 stating that tenants had been given notice to quit.

This left some allotments in the area the junior school’s log cabin now stands that were there from the early 20th century.

The current allotments between Hancock’s quarry and Monkton Combe school were certainly there by the turn of the 20th century – as the map below illustrates.

History of allotments

Allotments have been in existence for hundreds of years. Under the feudal system the open field system, a furlong was split into strips, of about half an acre. Each peasant had several strips allocated at a public meeting at the start of the year. They were scattered to prevent one person getting all the good land.

Peasants also had common land for grazing, fuel etc. As the population grew, the lack of land made it difficult to maintain the system and, from the 16th century, enclosure started to occur, as landowners saw they could make more money by having larger farms where they would decide the arable or livestock farming and the farming practices. In addition there was a growing population which lead to pressure on the open field and common land system.

When enclosing some landowners were unscrupulous and just evicted tenants, but if they could prove documentary evidence of their open field and common land rights some received an allotment of land in compensation. Enclosure lead to the agricultural revolution and a prosperous group of landed gentry but a many more landless and hungry poor.

Over 3,500 Acts of Parliament were passed between 1700 and 1860 to enclose over 5 million acres of common fields and land and less than 12% of people who worked on the land owned any. As enclosure increased, and the industrial revolution grew, more people moved into towns. It soon became clear that both rural and city poor needed something to help alleviate their poverty. Allotments were one answer but were strongly resisted by many farmers and landowners.

The food shortages experienced during the Napoleonic Wars led to some changes in thinking and the Select Vestries Act 1819, gave churchwardens and Poor Law Overseers authority to purchase or lease up to 20 acres of land and let it to the poor and unemployed of the parish as allotments.

The Swing Riots of 1830 and 1831 and fear of further unrest and Labourer’s Friend Society promoted extension to 50 acres, achieved by three acts passed in 1831 and 1832.

The General Inclosure Act 1845 required that the landless poor be provided with ‘field gardens’ as the rural land was enclosed. This helped in the countryside but city folk had no access to land. They began to push for allotments and urban allotment development began.

More progressive landowners, employers and clergy recognised that allotments could improve living standards and with the Allotment Extension Act 1882 that required trustees holding charity land for the use of the poor to set aside part of that land for use as allotments; the Allotment Extension Act 1885 allowing allotments to be let at the same rate as surrounding farmland and Allotment Extension Act 1887, that enabled Sanitary Districts to provide allotments by the compulsory purchase of land.

By 1890 County Councils were required to have an Allotment Committee responsible for holding inquiries if a Sanitary District failed to provide allotments.

At the beginning of the 19th century there were roughly 250,000 allotments.

In 1908 the Small Holdings and Allotments Act came into force and local authorities had to provide all the allotments demanded.

During WWI the number of allotments rose to 1.5 million.

After the war to help returning service men the Land Settlement Facilities Act 1919 was passed.

Allotment holders rights were strengthened through the Allotments Act 1922 and the Allotments Act 1925.

The latter established statutory allotments which local authorities could not sell or convert without ministerial consent. Under the Local Government Act 1929 agricultural and allotment land became non-rateable. There were 819,000 plots in 1939, 80% of which were urban plots, which increased 1.4 million during WWII with the Dig for Victory campaign, but the number fell to 300,000 by 2009.

An extract from “God speed the spade”: The History of Combe Down’s Allotments by Jacqueline Burrows

Jacqueline has been researching the history of Combe Down’s allotments since recent planning applications have revealed how little is known about their heritage, exposing the ease with which such cherished village assets can be threatened. She hopes to publish their complete story soon.

In 1851, Rev Newnham (1806-1893) developed the field garden allotment system “for the benefit of the labourers of Combe Down”, with yearly rents due each Michaelmas quarter day (29 September).

Tenants paid their sixpences at an annual allotment supper in the village schoolroom at which, amidst much excitement, they were waited on by the Vicar and his second wife Catherine, together with the schoolmaster and some of the local gentry.

This happy event can be traced over the next twenty-five years, until reports cease shortly before Revd Newnham retired in 1877. By October 1855, the Bath Chronicle tells us there were at least 31 allotments in Combe Down, managed by a committee.

Allotmenteering soon spread down the hill to Monkton Combe and in 1857, gardeners from both villages joined the annual meeting in the schoolroom. Rents paid and the Committee’s report read, a “comfortable hot supper” was served to the 44 tenants who were again waited on by Rev and Mrs Newnham and some of the local gentlemen.

A “small exhibition of large vegetables” took place.In October 1860, the coldest and wettest year on record, most of the 39 tenants in Combe Down made it to the annual event in the large new schoolroom, although fewer than half of the 17 Monkton Combe tenants ventured up the steep, muddy hill in the dark.

The meal was – as always – beef, with allotment vegetables and coffee to follow, with some “fine samples” of produce on show. After paying their sixpences, tenants were each given a penny halfpenny back to make up for the failure of the important potato harvest.

Then, as now, everyone went home hoping for better returns in 1861, when the tenth anniversary supper took place.

It didn’t take long to include a prize competition.

In 1863, rents were “for the most part, punctually and cheerfully paid” and a prize fund collection raised £8. Half was awarded to growers whose vegetables “would have done credit to Sydney Gardens”.

Everyone voted that the balance be spent on providing half-price steel forks for all, then went home at 9pm in “happy harmony.

Sadly, 1863 was to be the last joint supper: Monkton Combe’s allotment land was required for a grand new vicarage (now Westfield).

In 1865, the show was extended to include entries from private gardens. ‘It is hoped that this wholesome rivalry in honest labour and skill may tend to raise the character of the labourers, while the prizes offered by their richer neighbours proves their interest in the work.’

The supper was a grander affair too, with waiters being sent across from the vicarage. However, Rev Newnham didn’t come; Catherine had died a few months earlier giving birth to their sixteenth child.

He missed the 1866 supper too: he was in Weston Super Mare getting married for the third time!

By 1868, the show was taking place in the daytime and included entries from across the Down, including grasses and wildflowers from local schoolchildren, and the rent supper had become a separate evening affair.

By 1871 the annual show had become a major event, with the Vicar putting up his own money for larger cash prizes, attracting entries from a wide range of professional growers, gardeners and ‘cottagers’. It was even reported in the Bristol newspapers.

At the rent supper in 1872, the tenants presented Rev Newnham with the traditional inkstand, “in thanks for his kind services to them for twenty-one years”.

October 1875 saw the last report of a Combe Down allotment rent supper, at which the meal was “presided over” by Rev Newnham, now approaching his seventies. In 1877 he left Combe Down after 35 years as its vicar and retired to Corsham.

By 1895, responsibility for the village allotments had been taken over by Monkton Combe Parish Council and the annual rent collection had become an administrative task, carried out by a councillor without ceremony.

Perhaps the allotment supper on the Down with a small show of “fine vegetables” is a village tradition that could be resurrected, once we’ve all emerged from the complications of COVID19!

Jacqueline Burrows, Plot 8A2, Combe Down, 8 July 2020

Wesleyan Chapel

Wesleyan Chapel

Behind Glenburnie and adjacent to Gladstone Road is the Wesleyan Chapel which. according to Around Combe Down by Peter Addison was started in August 1854 and is confirmed by a cutting on the Bath in Time website.

It seems it was not a chapel for long becoming the coach house for Alma Villa (now Glenburnie). From 1922 when Edward Dudley (1847 – 1922), who had owned Glenburnie, died.

Glenburnie was then owned by Monkton Combe Junior School and the chapel became a dining hall. In WWII it was used as a food store then, after the war, as a playroom.

In March 1952 when Bryan Morris became Headmaster he felt that Monkton Combe Junior School ought to have its own chapel and in March 1952 the old Wesleyan chapel became a church once again and was dedicated by Bishop Bradfield of Bath and Wells.

By 2020 it had been converted into a private home.

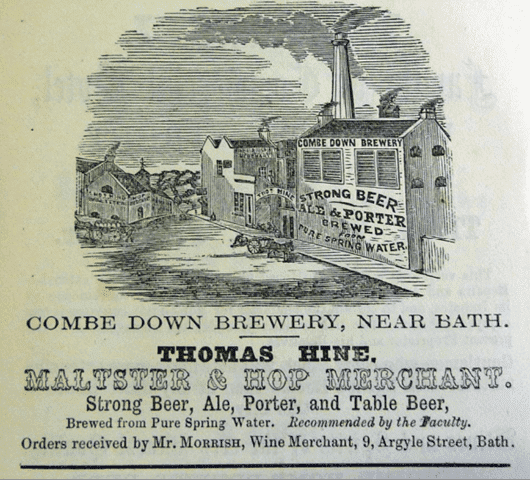

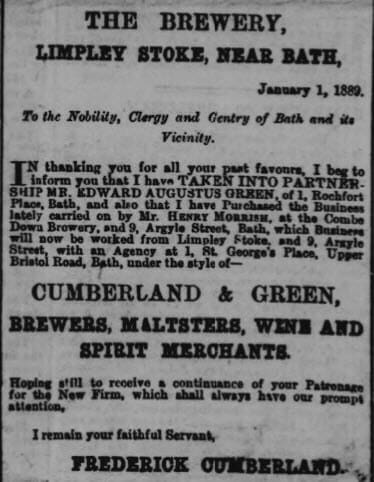

Brewery

Combe Down Brewery

In 1851 the Hulonce family, who were quarry masters, sold the remainder of their 99 year lease, which included the Lyncombe & Widcombe side of Ralph Allen Yard, to Henry Morrish (1804 – 1892), a Bath wine and spirit merchant, who paid off the £413 15s. 2d mortgage the Hulonces owed.

Some time later he formed a partnership with Thomas Hine (1819 – 1868), landlord of the King William IV. Together they developed the Combe Down Brewery, with a large brewery above the pub and a maltings on the upper part of Ralph Allen Yard.[6]

Henry Morrish and Thomas Hine were probably related. Thomas’ father Richard Hine (1786 – 1859) had married a Mary Morrish (1797 – 1877) in 1818 and it seems likely that she was a cousin or aunt of Henry Morrish.

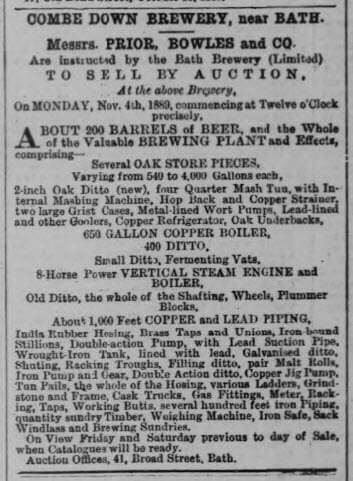

In January 1889 Cumberland & Green, a brewery in Limpley Stoke, bought Combe Down Brewery.

As noted in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette of Thursday 18 July 1889 they sold themselves to the Bath Brewery Company which was expanding and taking over smaller brewers. Combe Down Brewery was a casualty and closed, though, of course, the King William IV continued as did the malting yard.

By 1910 James D Taylor & Sons maltsters had taken over the maltings. They remained in operation until 1923 when they and the Bath Brewery Company were acquired by the Bristol Brewery (Georges & Co Ltd.). The company had begun acquiring its smaller rivals in and around Bristol from 1889 up until the 1950s, its last great acquisition Bristol United Breweries Ltd., in 1956.

In 1961 they, in turn, were acquired by Courage, Barclay & Simmonds Ltd. Its name was simplified to Courage Ltd. in October 1970. Courage was taken over by the Imperial Tobacco Group Ltd. two years later.

The maltings and yard were taken over by the local authority after the brewery was sold in 1923 and seems to have been used as stores until the outbreak of WW2 when it became a base for the ARP.

In 1968 it was still being used as a Council Depot.

In about 1970 the yard became known as Gammon’s Yard as Gammon Plant Hire took over ownership using the maltings for storage and the yard for heavy plant machinery.

It has now become Ralph Allen CornerStone and housing.

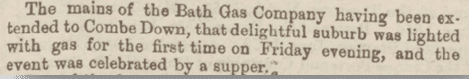

Public Lighting

Public lighting on Combe Down

In 1818, an Act of Parliament was obtained for lighting Bath with gas. The gasometer was located near the Upper Bristol road and over eighteen miles of pipe were laid; general lighting of the city started on 29th September 1819.[18]

By Thursday 2nd September 1830 the Bath Gas Company was extending the work and laying pipes in Lyncombe and Widcombe according to the Bath Chronicle. Over the years attempts were made to get the gas mains extended to Combe Down but the cost seemed to be prohibitive.[19]

It would take an Act of Parliament in 1865 to allow the Bath Gas Company to expand its capital, use rail transport instead of the Kennet & Avon canal and thus expand to include Bathampton, Bathford, Monkton Combe, Claverton, Englishcombe, Newton St. Loe, Corston, Saltford, Kelston, Weston, Box and Ditteridge.[20]

By 26th October 1865 the mains had been extended to Combe Down and public lighting was switched on.

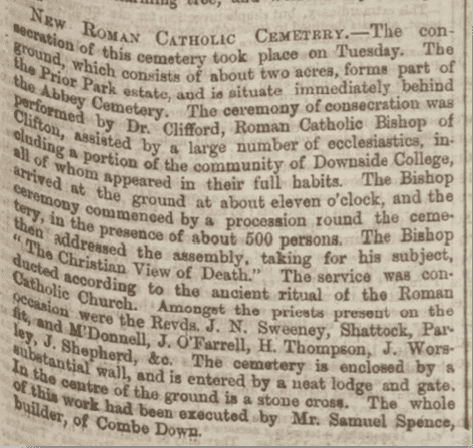

Catholic Cemetery

Perrymead Catholic cemetery

Perrymead Catholic cemetery at Pope’s Walk, off Perrymead, is adjacent to Bath Abbey cemetery.

It was consecrated in 1858. It has a mortuary chapel and the foundation stone for the chapel was laid on Thursday 2nd September 1858.[21]

It has a separate chapel for the Eyre family, members of which are buried in its crypt.[22]

The architect for this was Charles Francis Hansom and the chapel was built following the death of John Eyre (d.1861) who was a Count of the Holy Roman Empire.

The chapel was consecrated, on 13th October 1863, by the Roman Catholic Bishop of Clifton.

The Count’s two sons, Monsignor Vincent Eyre, Rector of Hampstead, and Father William Eyre SJ, assisted the Bishop at the ceremony. The vault under the chapel is still used for family burials.[23]

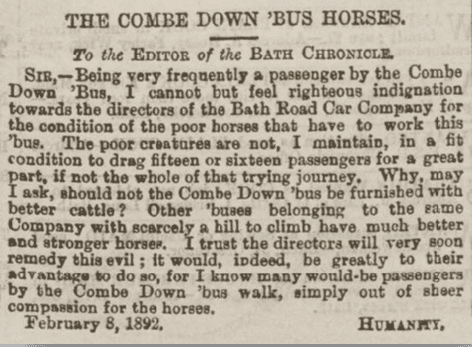

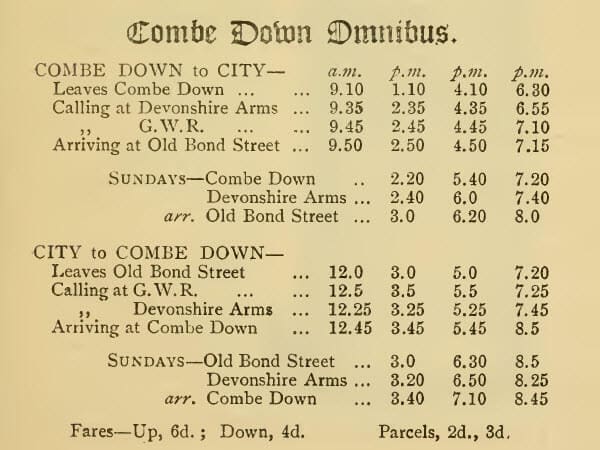

Omnibus

Combe Down Omnibus

An omnibus is a public transport vehicle carrying many passengers generally quite short distances.

John Greenwood ran the first English omnibus service in 1824 on the Manchester to Liverpool turnpike. He had a horse and a cart with several seats and offered a service that was different from a stagecoach as no booking was necessary and the driver picked up or set down passengers anywhere on request.

In 1829 George Shillibeer started operating a horse drawn omnibus service from Paddington to the City of London.[24] Omnibus services had started in Bath by 1840:

“Mr. Lane of the White Lion coach office, Mr. Reilly, of the York House, Mr. Pickwick, of the White Hart, and Mr. Clarke, of the Greyhound have started omnibuses, &c, to convey passengers to and from the Railway Station at 6d. each this judiciously making the best of circumstances, and getting all they can out of their gigantic rival.”[25]

The ‘gigantic rival’ was the railway.

A service was operating to Combe Down by 1866.

The horse drawn service continued until the advent of the electric trams in 1904. But the service was not without its problems. Horses could only work limited hours, had to be housed, groomed, fed and cared for and produced large amounts of manure, which the omnibus company had to dispose of. Probably ten or more horses were needed to work each bus in a day. Ill treatment of the horses was a problem.

“George Head of 3 Isabella Cottages, Combe Down, a driver in the employ of the Bath Road Car and Tramways Company was summoned for ill treating a horse, by working it in an unfit state and was fined £2 2s and costs.”[26]

There was much sympathy for the horses as letters to the Bath Chronicle show.[27] In 1892 it seems that the fare was 9d. down and 1s. up though Mr. T. Gould, who had, it seems, sold his business to the Bath Road Car Company says that when he ran it, it was only:

“……one shilling to and from Bath, with much cleaner and better accommodation than at the present time.”[28]

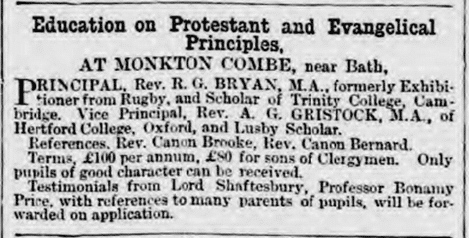

Monkton Combe School

Monkton Combe School

Monkton Combe School was founded in 1868 by the vicar of Monkton Combe at the time, the Rev Francis Pocock (1829 – 1919).

There were six pupils for the Lent term who were taught in his home.

In 1875 Rev Pocock became vicar of St. Paul’s in Poole[29] and the Rev Henry Wright ‘acquired the interest of the school’[30] which then had 18 pupils. He also purchased the advowson of the St Michael’ s church and conveyed it to the Oxford Churches Trust making it the church patron and affecting the appointment of the vicars of Monkton Combe for many years.

Henry Wright (d.1880) was Honorary Clerical Secretary of the Church Missionary Society and well off – he left £120,000 in his will[31] after he drowned in Coniston Lake having leapt from a boat but, becoming exhausted, failed to reach the shore.[32]

He appointed Rev Reginald Guy Bryan (1819 – 1912) as headmaster.

Rev Bryan was the Perpetual Curate at Fosbury, Wiltshire, where he had been for some 20 years and brought some of his pupils to the school. He was soon advertising for more pupils.

By the prize day reported in the Bath Chronicle in 1878[33] the school had 65 pupils.

Over the years the school has grown to over 350 pupils.

The Junior School was established with four pupils in 1888 in a private house in Church Road, Combe Down by Mrs. Howard (the daughter of the senior school principal Rev Reginald Guy Bryan) and moved into its current premises in June 1907.

The school chapel was opened in 1927.

The pre-prep was added in 1929[34] and moved into new premises in 2016.

Over the years the school has used many buildings in the area: Combe Grange, Combe Lodge, Combe Ridge, Scott House, Southfield, Glenburnie inter-alia.

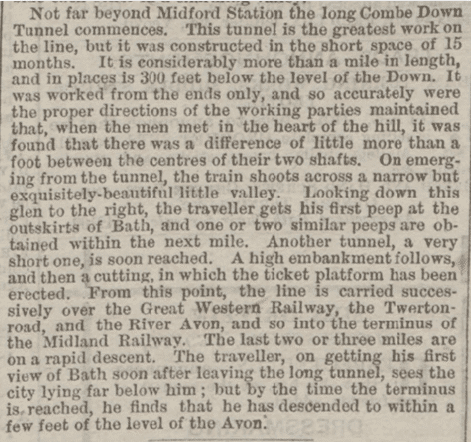

Tunnel

Combe Down Tunnel

The Somerset and Dorset Railway (S&D) was formed in 1862 by the amalgamation of Somerset and Dorset Central Railways.

In 1870, plans were made to build an extension to create a direct link between Bath and the Midlands with the South coast.

Work started in 1872. It cost £400,000 to build 26 miles and although it was successful the Company, which was not strong anyway, went into receivership and in 1875 it became jointly owned by the Midland Railway and the London & South West Railway.

On 20th July 1874 the Combe Down tunnel for the S&D opened to regular traffic.

The tunnel is 1,829 yards (1,672 metres) long and was the UK’s longest without intermediate ventilation. Combe Down tunnel was closed in 1967 but was reopened in 2013 as the two tunnels greenway walking and cycling scheme.

Whilst in use it was quite often more than a little problematic.

The article below shows how the great length of the tunnel combined with its lack of ventilation and the gradients of the line combined to cause those problems.

THE 1929 TRAIN WRECK

DRIVER TELLS OF FUMES IN COMBE DOWN TUNNEL.

MINISTRY’S INQUIRY INTO BATH TRAIN WRECK

Theory that footplate men were gassed

ANOTHER DRIVER’S GRAPHIC STORY

Journey through tunnel with handkerchief tied over face after spending a part of Thursday morning, and the whole of afternoon taking evidence, Col. A. C. Trench adjourned sine die his on behalf of the Ministry of Transport into the recent accident on a Somerset and Dorset mineral train just outside the L.M. &S. station in Bath. It will be resumed when the injured men —Guard Wagner and Pearce —are well enough to give evidence.

Somewhat conflicting evidence was given as to the smoky state of the Combe Down tunnel. One said he had found it very difficult to owing to the fumes when going slow.

Another said that when tender first he had never had a bad trip, and generally under those it was possible conditions it was generally possible to discern the roof. As the train tore by several witnesses none of them saw anyone on footplate and no one heard a whistle or a warning shout.

There was plenty of evidence that the brakes were on.

The Inspector first inspected the scene accident, and also the Combe Down Inspector rode the footplate from Midford into Bath to make himself conversant with track and other geographical conditions .

Among those present at the enquiry were George H. Wheeler (Traffic Superintendent, S. and D Railway), Mr. I W, (Traffic Department), Mr. R. C Archbutt. (resident mechanical engineer, (Highhridge), Mr. A. H. II . (Chief of Loco Department, Bath), Mr. Fox (Permanent J Resident Engineer, S. and D.), Mr. H. Rhymes (Chief Mechanical Engineer), Mr. G. (district Controller, L.M.S.), Mr. INT L – M – ‘ ineerin I j’tnient, Walsall), Mr. Worboys and I (Carriage and Wagon Depart\S \ M. and S.), Mr. Fisher (L.M. S), Mr. George Brown (representing South Western District, N.U.R.), Gregory (representing the Society of Locomotive Engineers & Firemen). Witness was Signalman W. H. who was charge of the junction signal box. He stated that the train correctly accepted, and came past his a very high speed. He did not whistle, and, far as he could tell the line was quiet..

SINTER’S GRAPHIC STORY.

Henry Wm. Crew said there was a din and heard the train go by at speed. He leaned out then and saw the tail end of the train down to the siding about 300 yards. He heard the engine leave then the crash. It was like the collision of a lot of coal. He rushed down to the siding it was mess said the witness. “I could spend years on the account. I felt the cabin shake way that made me think ‘what was going like that. Raw sparks from the brake van, but & probably have seen any from owing to the distance. I made way to the cabin, and was pushed back twice before I was successful- had my lamp, but could not see the steam. I judged from the hat the safety valve was blowing.

W F added that on the second he tried to enter the cabin hen’s legs protruding. He felt the end found it was beating. He got down put it on something inside ‘ and then found the head of *** up with his coat. I put ”************************” and the answer came *** “” ************* » a bad to scrape it out of eyes. Gas from the broken ***** office was coming over my bad to retreat. It was the I felt a afraid – Then I *********************************************************************************** his head, I think was deliberately wrapped over head. I found his clothes were smouldering and that was rubbed out. was driven back the intense heat, but there was very little steam then. then found another man lying in the permanent way. Meanwhile others had got into the cabin. The firebox was practically full, and it turned over it was coming over the bridge on to the footplate, where the men were lying.

The Inspector : When the engine came round as far as the junction, were you surprised it kept the rails?

Witness: I was surprised, and the feeling of the movement of the hut made me look out. The Inspector congratulated Mr. Crew on his efforts to get Fireman Pearce out.

Shunter C. H. Hill was next called, and he told how he and two others were standing on the bridge over the road waiting for the train to come in when Inspector Norman came out and shouted: “Clear away. Look at this engine.”

SPEED OF TRAIN.

Witness estimated the speed of the train at from to 60 miles an hour. Spirals were coming f;om the w heels of the engine it passed “The wheels were all afire.”

The Inspector : Did you see the driver or fireman on the engine it passed?

Witness: No, did not sir. Witness proceeded to describe how he came across the body of Loder, and took part in the rescue operations Shunter W. F. Day gave evidence supporting that of the previous witness. Checker Richards, who .aw the train coming down into the siding faster than usual and was obliged to run clear, said there was no shout of warning. Sparks were coming from the tender wheels. He could not see the inside of the cab from where he was. It passed him at be 50 and 100 miles an hour.

Driver White, who was taking his engine into the S. & D.J.R. sheds, and was attracted to the ill-fated train by the tremendous noise, said he saw the whole train pass at a very high speed. His experience of these engines was that when the brakes were on there was a distinct rail fire round the tread. Sparks came from the top of the wheel, not the bottom. At the time he thought the brakes were on. It did not appear to him, on consideration, that they were. The sparks at the top of the wheels were, he suggested, caused by the tremendous rock of the engine, which resulted in contact between the flange and the frame of the engine. There were no sparks from the tender wheels.

The Inspector: I take it that is opinion you give with some reserve. You would not like to express very definite opinion. It is only a suggestion? ,

Witness: That is so.

TROUBLE FROM GASSES.

Witness added that his impression was that steam was on. He did not recollect seeing steam coming from the chimney. The engine was making a tremendous noise, and there was rattle of the wheels different from what had heard before.

Witness did not examine the engine. “I was too shaken. could not seem go near it There were plenty more around her,” added witness. Witness had worked trains over, the same section of line.

The Inspector: Have you ever had any trouble with that tunnel?

Witness: Yes, sir.

The Inspector: What trouble?

Witness: Trouble from gasses.

The Inspector: What do you mean, that breathing has been difficult?

Witness: Very difficult. He related one experience early this year. He started at dead from with a similar engine and full load, reaching Midford tunnel always at walking pace. He was tender first.” Just inside the fireman cried out. The smoke was bad. He tied a handkerchief over his nose and told the fireman to do the same, which he did. He crouched down on the footplate with his bead just outside the tender wall to catch the current of air; his left hand continually working the sanding gear. The steam made things worse. jumped and added coal to the fire, getting down again sharply. He wanted to keep the boiler pressure up to keep moving. The fireman did the same. The engine was not slipping. The tunnel was often wet and wanted care in the use of sand. They managed to crawl out of the tunnel very very slowly. soon as he saw a gleam of daylight he shut off the steam and was prepared to stop as soon as he got outside the tunnel and see how things were before going into Bath. He did not stop, but took five, eight or 10 minutes to reach the mouth of Combe Down tunnel. Replying to further questions witness said he felt the effects of it for a day or two afterwards and his fireman also complained about it. He thought the fumes were from his own engine, because the wind was following and keeping with them all the time.

AUTHOR

HIS THEORY.

The Inspector: Have you any views to what happened on this occasion ?

Witness: That the only thing. They were overcome by fumes and down there and did not know what was happening.

The Inspector pointed out that they had had a good deal of evidence that the brakes were on.

Witness expressed the view that possibly the steam pressure may have dropped back owing to the circumstances, and could not operate the vacuum. The brakes on that type engine were really good brakes, and his opinion was if they had been applied they would have been bound to have stopped the train. In answer to Mr. Symes, witness said he was having a little trouble with the engine and for that reason it took him much longer to get to the mouth of the tunnel. He usually entered the tunnel much faster. He knew was in for a bad time. The stand at Midford did not improve the fire.

DISLIKED STOP AT MIDFORD.

Mr. G. Brown asked witness his opinion of the causes why the train, which came to grief, was long on the up-gradient? Did he think it arose from falling steam pressure in climbing the gradient, especially as the load was under schedule ?

Witness said he would put it another way. Witness and his fireman were in full possession of their faculties, and were keeping up the steam. If the other two men were down and out through gases the train would come through very slowly.

Inspector: Would it keep on without firing ?

Witness: I think so. explained that drivers were anxious to get steam up as much as possible before entering the tunnel to avoid firing in the tunnel, and especially was this the case if there had been a stop at Midford.

Mr. Brown : Is the anxiety to avoid the chance of sticking in the tunnel or slow running through the tunnel? — The two things together. glow running would probably mean a stick.

Mr. Brown: I am asking what the anxiety arose from ? —To get through the tunnel.

Inspector : And to get through quickly ?

—Yes. Witness said he were working a train with a full load and knew there wae passenger train coming from Bath he would endeavour to regulate his time and speed so as to get a clear run through Midford.

PUTTING ON THE BRAKES.

Mr. Brown asked if any special instructions had been given for working on an incline, other than the ordinary rules? Mr. Wheeler remarked that they understood the load capacity had been governed by the holding power of the brake. He did not think the question of engines not being able to hold the load had ever arisen. Mr. Symes asked what was the practice with regard to the manipulation of the brakes coming out of the tunned in the ordinary way. Witness replied that in the ordinary way the moment he saw daylight at the end of the tunnel he should shut the steam off. He would then on the level and the train would “drive” out of the tv The fireman, immediately on coming out, would screw his own brake on tight. Witness would apply the steam brake and the guard would, of course, use his judgment then to apply his brakes.

BRAKES NOT APPLIED.

Signalman Gardiner, whose home Pigwood Road, said he was standing at the back door of his house within about 20 yards of the track and saw the train going by. The engine was in full steam, which was coming from the chimney. The speed was roughly 50 miles an hour, and he saw sparks flying from the wheels, but the brakes did not appear to be applied.

PREVIOUS PASSENGER TRAIN.

Driver Bowles, who had driven a passenger train into Bath, which had preceded the ill-fated train, said when he came through the tunnel it was much the same as usual. Witness’s engine was not steaming more than usual.

The Inspector: Have you ever lad difficulty in breathing there?

Witness: Oh yes. Several years ago it was very bad. He proceeded to state that being a passenger driver he would not be in the tunnel so long as a goods driver. The tunnel was clearer now than in the old days of saturated steam.

Relating his story of the accident, he said he was walking home in the road about 100 yards from the track when his attention was drawn to the trucks passing at a higher speed than usual. He saw sparks coming from two or three of the wagons. He did not think it was from the brakes. It was probably the result of derailment. * Colonel Trench elicited that the pressure fell so low that it would not maintain the vacuum the steam brake went on. “That,” added the Inspector, “is the position here as we understand it.”

BEEN HAVING TROUBLE.

Signalman E. J. Larcombe, who was Midford signal box on the day of the accident, said the train left Wellow at 4.53 p.m. and arrived outside the outer-house signal at 5.2 p.m. He gave particulars of the movements of certain trains during the afternoon hours.

After the Bournemouth passenger had passed, Driver Jennings came to him and said he had been having trouble, and asked to be allowed to stand until the passenger train had got to Bath. He asked to be allowed to take the “tablet” with him so as not to have to slow up to take it as he passed—to get a better run. He gave no idea to what was the matter, except that he was having steaming trouble.

He realised he had a heavy load. Witness had known drivers fail to get through the tunnel and come back. There some wind on the afternoon, which, possibly, might easterly. The tunnel cleared quicker some days than others— when the wind was north or south. When the driver passed witness’s box was doing what was the usual speed of trains similarly situated—ls to 20 miles an hour. Examining Fitter Bolt, S. and D. Joint Railway sheds, said on the Wednesday before the accident.be tested the brakes on the engine and found them all right. He signed the examination book to that effect.

SAW NO ONE ON THE FOOTPLATE.

Driver Frank Porter, L.M.S. driver who was working with a shunting engine was at a dead end near the junction signal box. The train passed the next line to witness, and he heard no whistling. The speed he estimated to be 45 to 50 miles an hour. Pie saw sparks coming from the engine wheels, and it seemed to him the brakes were on He saw no signs of any steam. The tender brakes were on, but he would not give a definite opinion that the engine brakes were on owing to the spark blowing back. In the case of the brake van also the brakes were on. He could not see any figures the footplate as the train passed, and was rather surprised not to see any. He was looking out for the tablet to be thrown out, which was done into a net. The engine was swaying. Fireman Shipp, mate to the previous witness, gave evidence of a similar nature. “As I looked at the engine to try and see who was driving I could see no one on the footplate. The footplate was in darkness. I did not see any smoke or steam of any description,” said witness.

PREFERRED TENDER FIRST

Driver Hockey, of the S. and D.J.R., who worked the same engine the previous day, said he took slightly heavier load to Evercreech—the opposite way— and beyond Masbury there were gradients as had as this end—a good deal, 1 in 50. The engine was steaming fairly well, and, considering the load, did very well.

Asked he had any trouble with slipping, he said all of these engines slipped. He returned with a train rather tight. The sanding was all right with engine 89. The tunnel in question was a bit dirty, and engine first it was sometimes bit nasty. He had been tender first with these engines as often as anybody, but he had never had a bad trip. Asked he preferred going tender first, he said, Yes, if we were not dealing with the weather; and have been advising turn-table at Bath. (Laughter). would,” he added, prefer going through a tunnel tender first. Ninety times out of hundred they could examine the top of the tunnel, the atmosphere was so clear. one were engine first it had only to make slip or two and it was difficult to see whether the engine was going forwards or backwards.

Once had asked his fireman to see which way they were going. (Laughter). Coming tender first he had never had a bad trip.” What beat him was that Driver Jennings and his mate found it so bad. Replying the Inspector, witness said he went through the tunnel on the 5.15 p.m. goods out of Bath, and did not then find it very bad. This would be about 40 minutes before the train which met with the accident. Replying to Mr. Brown, witness said a full head of steam on this particular engine was 1901bs, and going up Radstock bank he would not want to drop much below 170lbs. J he Inspector asked the witness if could envisage the possibility of both the driver and fireman being overcome as they came out of the tunnel, and the engine worked up uncontrolled just managed to come out of the tunnel, with steam pressure falling to about l00lbs., and then letting the vacuum brake on

Witness: I never entertained that myself, sir.

The Inspector: What is your solution

THOUGHT THEY OVER-RAN.

Witness: I think they overran coming out of the tunnel. I think they came oux a bit reckless. But there i» one solution to that I cannot fathom. Why did not the men blow the whistle to warn the people down here? Replying to a question by Mr. Brown, witness said perhaps the word reckless was hardly the right one to use. What he meant was, he came out of the tunnel at too fast speed for the condition of his engine. If he had not sufficient steam should have come out carefully as he would not have sufficient braking power. Driver Iley, S. and D.J.R., stated that he drove the same engine on the Friday previous, to Evercreech Junction, with a full load. The engine was not steaming well. Some were better than others. He could not give any reason. He had difficulty in getting the bank, and lost five minutes between Bath and Masbury. He had had other engines of this type, and occasionally they were in poor condition. He had never had any trouble with the brakes. They were good brakes. In answer to Mr. Symes, he said soma days an engine would steam well and some days would not.

THE LOCO. SUPT.

Mr. Whittaker, the Locomotive Supt., said on his arrival at the scene of the accident his attention was drawn to the fire-box because a fireman wanted to squirt water into it. He said he must do on no account. He could through looking through the ashpan, there was nothing inside to hurt. There was a fire in it, but it was well contained and not spreading. He then got on the footplate to see whether there was any pressure. None was showing on the gauge. The reversing gear vas almost in full gear and locked. The regulator one-third open; that was, to the pilot jet. There was no steam at all. He did look at the brake blocks till next day. The steam pipes were all intact, and the connections of the brakes were also all intact. The next day found tho brake blocks holding on to the engine wheels. They were in good condition, and well fitting throughout. The sanding apparatus was open.

Inspector: Was there any sign of the regulator of its having been pushed opea a blow?

—I found nothing like that.

I suppose there is no chance of the reverse gear being moved accidentally?

—It was impossible, because the cab had been forced against it. Mr. Whittaker said on getting into the cab he found the hand brake moved a little. From an examination after the engine had been shifted, he concluded that it was clean off.

The Inspector said the steam brake was on, but when steam died away the brake came off. Mr. Brown said he was under the impression all the time that the under brake was on.

The Inspector: I think the under brake ,was on, but not enough for hard brake application. enquiry was then adjourned, the Inspector intimating they would have to meet again when the injured guard and fireman were well enough to attend.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

BATH RUNAWAY TRAIN DISASTER

Inspectors Report to the Ministry of Transport

ENGINE CREW GASSED COMBE DOWN TUNNEL

Risk Removed by Lightening North Bound Train-Loads “I am led to the conclusion that both driver and fireman were overcome by smoke and fumes while passing through Combe Down Tunnel, and that the engine emerged from the tunnel uncontrolled.”

In this sentence of his report to the Ministry of Transport, Col. A. C. Trench, the inspector who investigated the recent Bath train smash, epitomises his view of the cause of the disaster.

“The tunnel has been in use fifty years without any similar case of the engine crew being overcome by fumes, but, although the chances of a recurrence of the adverse factors which prevailed on the day of the smash may be remote, the Inspector holds that the risk not one that should be taken.”

SAFEGUARDS.

The most obvious safeguard, he says, is by improvement in the tunnel’s ventilation, either by a vertical shaft or by fan or forced draught, but these measures would entail so heavy a cost to be hardly justifiable, and the remedy he recommends instead is that there shall be a substantial reduction in the load north-bound trains to Bath. The Railway Company, we understand, have already put this recommendation into operation, and have reduced the loads by twenty-five per cent. There have been no complaints of difficulty since.

THE INSPECTOR’S CONCLUSIONS.

The accident, it will be remembered, mentioned under (b) below, occurred about 6.37 p.m. on November Overpowering of engine by weight of 20th in the Bath Station Yard on the train and/or brake failure. The weight of the train was within the authorised L.M. and S. Railway. The 3.25 Somerset. made for thigs class of engine being met and Dorset goods train, Evercreech Q quarters,’ as against 172 to Bath, ran away down the steep quarters maximum permissible, gradient from Combe Down tunnel to (This system of reckoning based on the Bath Junction, and, after being ********** loaded mineral wagon countrailed, at high speed, at the entrance our quarters,” and heavier to the Bath Yard, collided with and vehicles proportion, according to a completely wrecked the near end a fixed scale).

The brake equipment building used by the railway clearing was found to be in good order after the house staff. accident, with the exception of Three men were killed—Driver J. H. breakage on the Bissei truck, Jennings, Inspector Norman and Mr. Dentiy due to derailment. The brake Jack Loder, a railway clerk ; Fireman blocks had been reported by a driver Pearce and Guard Wagner were seriously previous as requiring injured. taking up and they had accordingly After reviewing the evidence taken at adjusted on the morning of the his inquiry at considerable length, accident. They were in good condition Colonel Trench sets forth his conclusions and had required nothing more than follows:— normal attention. The rail was dry. Certain points regarding this case may ************* engine was be disposed of very briefly. There are no ********** but after accident questions of defective condition or era *********** found the sand ************ of points, signals or permanent way. used There is no doubt that the speed of the ‘ train at the moment of passing Bath-

BRAKES NOT OVERPOWERED

****************************** The evidence of several drivers with or safe, and various witnesses experience of this type of engine and similar pressed surprise that the ************** kept to the loads on this line was unanimous in that rails when negotiating the facing points they had never had any trouble with and curvature this point. The final de-braking. railment was the natural and almost The most definite objection to the theory inevitable result of this excessive speed. of overpowering is, however, the fact that The investigation must, therefore be attempt had been made to reverse the directed to the determination of the cause engine nor to apply the hand brake on the of the excessive speed. *************; the question of when the steam Possible causes of excessive speed are brake was applied on the engine and tender (a) Carelessness or reckless driving on the discussed further below, but it was ***************** of the driver at the top ************* not applied for most of the descent, down gradient, with subsequent in- addition, it is guile clear that there ability to stop.

NO CARELESSNESS.

************************* think, may dismissed at once, (c) possibilities (a) and (b) above being Driver Jennings was a man of 57 years of thus ruled out, the only reasonable age, with 39 years’ railway service, passed alternative is that during the descent driver in 1915 and made driver in 1919. He from Combe Down tunnel neither of was intimately acquainted with the line, the men on the footplate was in a the engine, and the working of similarly condition capable of taking any action laden trains, and he had a very good to control the train, ************ record. It inconceivable that he could ported by the following evidence, as wittingly have allowed his train to attain well by a number of the preceding such an excessive speed on this steep items. gradient, having regard also to the points

The evidence of Fireman Pearco and enter the tunnel (from the Midford end) at a fair speed, they are not in the tunnel long enough for conditions to become ‘ serious, and that trouble is liable to arise only when they are stopped at Midford and have to re-start with a heavy lead up the severe gradient leading to the tunnel.

There appears to be no question of any difficulty in traversing the tunnel in the south-bound direction. The simplest remedy would be, therefore, to make a substantial reduction in the permissible loading (north-bound; over this section of the line, or, necessary to provide a banking engine from Midford the southern entrance the tunnel. In addition this, it would be desirable to arrange as far as possible that north-bound goods trains, which have to detained on the south side of the tunnel, should be detained at Wellow rather than at Midford, so that they can run through Midford and not have to start against the severe gradient.

Combe Down tunnel gas and crash

Owing to the limitations of single line working, recognise that this may not always be convenient. I understand that the question of the reduction of permissible loads is now under consideration by the Company. would recommend that a close watch be kept on the results attained by any such reduction, with a view to confirming the adequacy thereof, or, if necessary, the consideration of further measures of amelioration, such arrangements for ventilation.

“TENDER-FIRST” DISCOMFORTS.

A further point which arose in the course of my Inquiry the fact that, owing to these engines being too large for the turntables available, they have to work through the tunnel tender leading when travelling towards Bath. Some of the evidence inclined to a theory that operation with tender leading accentuates the discomfort of the smoke and fumes, by reason the engine cab forming cup which tills the tunnel, and tends to collect and intensify them. On the other hand, it evident that, with this arrangement, the chimney being in rear of the cab, there must be a tendency to leave behind the smoke from engine itself, and, except perhaps when the engine is moving at an unusually low speed, one would expect that the tender leading arrangement might be preferable. The evidence of driver on this point was neither unanimous nor convincing, and 1 doubt whether “the fact of working tender leading had any direct bearing on the regrettable accident. It may noted that the first five of this class of engine, constructed in 1914, were fitted originally with tender cabs, but 1921 the cabs were removed from the tenders, view of complaints that they were inconvenient and uncomfortable. It should be possible to form a fairly conclusive opinion tunnel conditions, tender leading compared with chimney leading, from the results of a few practical experiments, and, before it is decided to continue indefinitely a regular practice working these large engines tender leading, I consider that such investigations would very desirable. If the results were such to support the argument that working tender first seriously objectionable, the provision of adequate turning arrangements should receive further consideration by the Company.

‘STIP’-STONE.

Former Bath ********** Illness After Tunnel Trip. “The report of the Government Inspector on the train smash at Bath, in Saturday issue must have been specially interesting reading to any who remember the construction of the line and the early days of the tunnel,” writes an old Bathonian. “As a school pupil’ whose master was keenly interested in his pupils and imbued them with a love of nature study, we were encouraged to find out all we could about the fossils and rocks, and the uncommon botanical growths which billowed their removal to the open. What appealed most, perhaps, to the boys was the “stink stone” which the navvies found in the tunnel. For a considerable time after the tunnel was first opened complaints were very general on the part of passengers, and gave the officials of the line much anxiety, of the foul gases which prevailed in the tunnel. There were many complaints of illness popularly attributed to smells in the tunnel; notably the illness and death of the Rev. Charles Kemble, Rector of Bath. It was a considerable time before adequate ventilation was secured to overcome the trouble.” Guard Wagner, that the tunnel wa6 on this occasion exceptionally hot and smoky and that after a short distance Pearce had to wrap a coat round his, head and sit down, after which he remembered no more. The fact that after the accident the position of the bodies of Driver Jennings and Fireman Pearce was such that it seems probable they must have been lying on the footplate at the moment of derailment. The fact that none of the nine or ten ‘ witnesses who saw the tram pass more or less close proximity saw anyone on the footplate.

IN THE TUNNEL.

The evidence that the tram was an unusually long time in the tunnel, and the inference that the engine was probably labouring heavily for most of the time. I am therefore led to the conclusion that both driver and fireman were overcome by smoke and fumes while passing through Combe Down Tunnel, and that the engine emerged from the tunnel uncontrolled.

Having regard to the falling gradient, it can be shown by calculation that, even assuming the engine was only just moving at the exit from the tunnel, it might well have attained a speed of 60 miles an hour or more at the foot of the gradient, in spite of the guard’s brake application. The above conclusion has been confirmed by medical evidence at the adjourned inquest on 17th February, when the medical officer who had been asked the Coroner make a post-mortem examination of Driver Jennings, stated that he had found there was at least per cent, saturation of the blood with carbon monoxide, and that as a result Driver Jennings must have been either unconscious, or on the borderline of unconsciousness, in such condition as to be helpless to perform his duties.

The fact that the engine and tender brake blocks were found applied after the accident can be explained in two ways, either that the fracture of the tender vacuum connection applied the brakes while turning over, or that the engine descending the gradient at high speed in full gear, with regulator partly open, drained the boiler of steam to euch an extent that the vacuum ejector failed to maintain the vacuum and thus applied the steam brakes. It was found by experiment that when boiler pressure had fallen to lbs. the vacuum failed to the degree necessary to apply the steam brakes Such application would, of course, be gradual, and the retarding effect the steam brake with such low steam pressure would be trifling. The point is not, however, very material, as, whether the brakes were not applied until the derailment or only lightly applied near the end of the run, in neither case would they have had any appreciable retarding effect.

RECOMMENDATIONS.

Lightening the Load of North- Bound Trains. This tunnel has been in use for over years without any similar case of the engine crew being overcome by fumes, and for the last years this class of goods engine, with practically the same maximum loading, has been traversing the line; from the evidence of a number of drivers and others it is fairly clear that under normal circumstances the atmospheric conditions are not euch as to involve any risk or thing more than a degree of discomfort.

All witnesses agreed, however, that occasionally conditions were very bad, and it seems probable that such conditions are produced by a combination of adverse factors, such as smoke from trains immediately preceding, an engine labouring heavily, and, possibly, slipping, and unfavourable weather conditions, with high humidity and absence of wind. All these factors were present to a marked degree on the occasion of this accident. Although the chance or the recurrence this combination of the adverse factors may remote. I cannot think that the risk om. that should be taken, having regard to the evidence given to me by various drivers and others, and I discussed with the Company’s officers the various means of avoiding such risk in future.

VENTILATION MEASURES TOO COSTLY.

The most obvious method of doing this by improvement of ventilation, either by vertical shaft or by some arrangement of a fan and forced draught. Unfortunately, either of these schemes would very costly and can hardly justified, any rate until simpler schemes have been tried.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

RUNAWAY BATH TRAIN MYSTERY SOLVED

Practically Unconscious on Footplate

CONTROL LOST THROUGH BEING GASSED

Doctor’s Emphatic Evidence

SATURATION OF BLOOD WITH CARBON MONOXIDE

Evidence was forthcoming at the resumed inquest on Rail Crash victims on Monday confirming the theory crew of the ill-fated coal train were ” gassed

DRIVER ALMOST UNCONSCIOUS

75 Per Cent. Saturation of the Blood With Carbon Monoxide. The Coroner said that after the inquest was opened he had one or two interviews with officials and he asked Dr. Scott White to make another post-mortem, because they considered there was probably some evidence to the driver having been gassed.

That evidence he had not heard, and he would ask Dr. Scott White to give now. Dr. E. Scott White, ot Green Park, said on November 23rd he made a further examination of Jennings, and confirmed his previous findings as to the injuries, and also made a further examination of his blood. He first of all stated that in the left lung he found some old pleurisy. Apart from that the organs were normal to his age. On putting the blood to spectroscopic and clinical tests, found that there was at least 75 per oent. saturation of the blood with carton monoxide. ” In my opinion at the time he would certainly be unconscious.”

The Coroner: Are you speaking of the time of the death?

— Yes. Tbe degrees of unconsciousness vary in each individual, and it is impossible for me to state what degree it would be his case.

You say he would be unconscious? —He would have been on the border-line of unconsciousness one way or the other.

What you found was what you expected to find ?

—On the Thursday got, practically the same test. Of course, on the Saturday I took larger quantity of blood.

On the Thursday you did not find any trace?

—Oh, yes, did. But you did not ask me anything about it then.

GASSED IN THE TUNNEL.

In further answer to the Coroner, the doctor said the real cause of death was the injuries, but the state of unconsciousness undoubtedly led to them.

The Foreman: tn order that we may clearly understand, would you put it down to asphyxiation in the tunnel ?

-lt is quite a totally different thing. That word is usually used where there a lack of oxygen. I do not think there is any I lack of oxygen in the tunnel. The same thing you get in coal gas poisoned him. Was he actually gassed the tunnel rendering him helpless to perform his duties?

— That is my opinion.

THE GUARD EVIDENCE.

Never Known the Conditions So Bad Before.

Christopher George Wagner, of Belvoir Road, a goods guard on the L.M. and S Rlw., gave evidence which bore out that which he gave at the resumed hearing before the Ministry of Transport inquiry. He told how he realised the train was cut of control and made up his mind to jump, and how the atmosphere of the tunnel seemed thicker than usual. Replying to the Foreman of the jury witness” said his brake was a 21-ton brake. They might have been 10 or 11 minutes coming through but he had known them 1 do the journey in eight or nine minutes. He had never known the conditions quite so bad before. He could not say whether it was better for the train to come through with the engine first, thereby dispersing the* fumes to some extent and keeping them from the men on the engine. There was no ventilation in the tunnel, Walter Henry John Cooper, of Staple Hill, Bristol, relief signalman, who was on duty at Bath Junction signal box, stated that the train passed his box at 60 miles an hour. He was surprised that kept the rails. He received no indication from the train crew that the train running away and no whistle sounded. He looked for the tablet after the train had but could not find it. There was a limit of five mile at that point.

SMART BIT OF WORK.

Henry William Crew, Coronation Avenue, a shunter, said was in his cabin at the time and the train, which wa» going at a faster pace than any he had seen before, shook it. He ran out and saw the crash. He ran to the spot and groped about in the wreckage for any bodies. Fireman Pearce was covered with coal and there wa6 a coat over 1m head. Pearce was got out. He did not know till afterwards that tbe body of Jennings was underneath. Mr. Beale (for the Company) thought witness did a very smart piece of work finding the puss in Pearce’s leg to ascertain if he were alive. It showed the value of his ambulance ability. Only a trained man could have fastened on the spot under those difficult conditions. He (Mr. Beale) had not previously heard of the fact. The Coroner said he agreed with those remarks and was glad to tell witness that Pearce was really getting quite well again. The jur; endorsed what had been said about witness’s skill.

BETTER ENGINE FIRST.

George Thomas Boushor, of Ringwood Road, a driver on the L.M. and S., who was a witness at the Ministry of Transport inquiry, also gave evidence. He usually put handkerchief round his mouth when going through the tunnel. It was only occasionally when conditions were bad. He had always found the brake power of the type of engine involved in the accident sufficient. There was no wind on the day of the accident to blow the vapours through the tunnel. Replying to the Foreman, witness said they found it better going through the tunnel engine first than tender first, especially on the higher engines. The Foreman: Tho engines are so big that they fill the hole in the tunnel?— Yes. The Foreman: It ought not to be called tunnel really. Witness added that bad coal affected the conditions in the tunnel. To another question by the foreman, witness said there was no turntable at Bath large enough on which to turn engines of the type involved. That was partly the reason why they came in tender first, so as to have the engine first going out of Bath when they had a heavier load.

CORONER’S SUMMING UP.

The Coroner, summing up, said that was the whole of the evidence he thought it absolutely necessary to bring before the jury. He had been able to see the statements ‘of other witnesses who appeared before the Ministry of Transport inquiry, but he did not think they would help very much in arriving at their verdict. He had hoped that they would have had the report of the Transport inquiry there for the jury to consider, but that inquiry had not been actually concluded yet, and therefore he could not bring it before them. was terrible accident, and the more one lingered it the more terrible appeared the loss of lives to the relatives and friends. There was only one thing he could advise. The deaths were due to injuries received through an accident, and that accident arose through the train being out of control. There was a brief consultation between the Coroner and the Foreman, and the jury then retired. The Coroner mentioned that the foreman had simply asked a question in connection with the men being gassed. He said if the men were gassed that was how the train came to be out ot control. That probably was so, but as a matter fact, the jury had not to inquire how the train got out of control. He ‘the Coroner) suggested to him that all they really had to inquire into was, what was the cause of death, and death was caused because the train was out of control. He did not think they could go any further into it, and saj why the train was out of control. The jury commended Shunter Crew and P.C. Bransgrove for the assistance they rendered.

THE VERDICT.

Loss of Control Through Being “Gassed.” After a brief retirement the Foreman said the jury’s verdict was that Driver Jennings’ death was caused by his losing control of his train by being rendered helpless by gas fumes in the tunnel. This loss , of control caused the deaths of Sidney John Loder and Inspector .John Norman, and serious injury to Fireman Pearce and Guard Wagner. They wished to associate themselves sincerely with the Coroner in his sympathy with the relatives and to commend Shunter Crew and P.C. Bransgrove for the prompt assistance they gave at the time of the accident.

The Coroner: I take that is verdict of “Accidental death” in the case ot Jennings in the first place.

The Foreman said the jury could not get away from the fact that the doctor s evidence showed that the driver was rendered helpless or unconscious by fumes in the tunnel and lost control of the train.

The Coroner: That is case of Accidental death” of course.

The Foreman: If you feel that construction upon it we can say it was accidental

The Coroner said it was accidental death in each case through losing control of the train owing to the gas in the tunnel. The Coroner: It is merely case of accidental death in all three cases. Mr. Beale : There is no criminal liability, and therefore it must be so.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

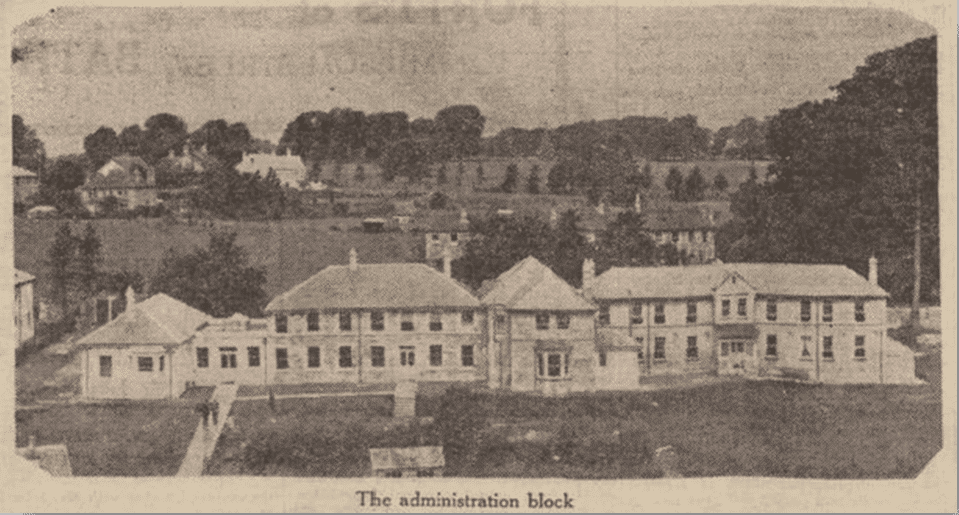

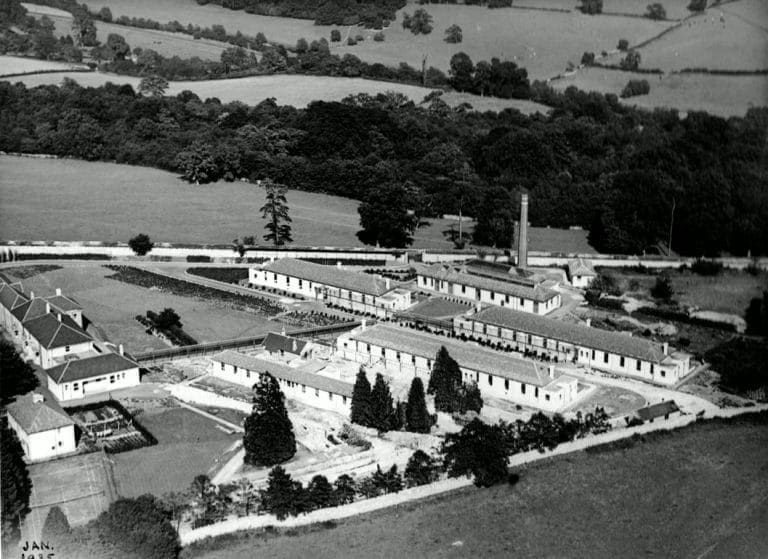

Convalescent Home

Combe Down Convalescent Home

The Combe Down Convalescent Home was founded in 1870[35] but soon proved inadequate in size.

Many bazaars and concerts were held over a number of years to raise the money to build a larger home.

By 1880 enough money for a 12 person home had been raised, though fundraising continued. An acre of land was donated by Mr. Vaughan Jenkins of Combe Grove.[36]

The foundation stone was laid on Thursday May 27th 1880 by the Mayor of Bath[37] and was open for business in 1881.

Convalescents had come to Combe Down since the late 18th century, but the changing nature of medicine in Victorian times – more medical training and doctors, nurses and hospitals to go along with the scientific advances based on Louis Pasteur’s work on germ theory and Joseph Lister’s introduction of antiseptic processes – meant that more and more people actually survived illness and surgery and needed to convalesce.

Those with enough money wanted to do so in pleasant surroundings with trained staff. Over the years the convalescent home expanded to treat over 400 patients a year.

According to Dr David Carr the home was taken over by the RAF during WW2.

After the war it reopened as a private home for women patients but with the founding of the NHS on 5 July 1948 it began to take in post operative convalescent cases, mainly from uterine surgery, from the Birmingham area NHS.

As the NHS and medical practices progressed convalescence became less of an issue and numbers began to fall.

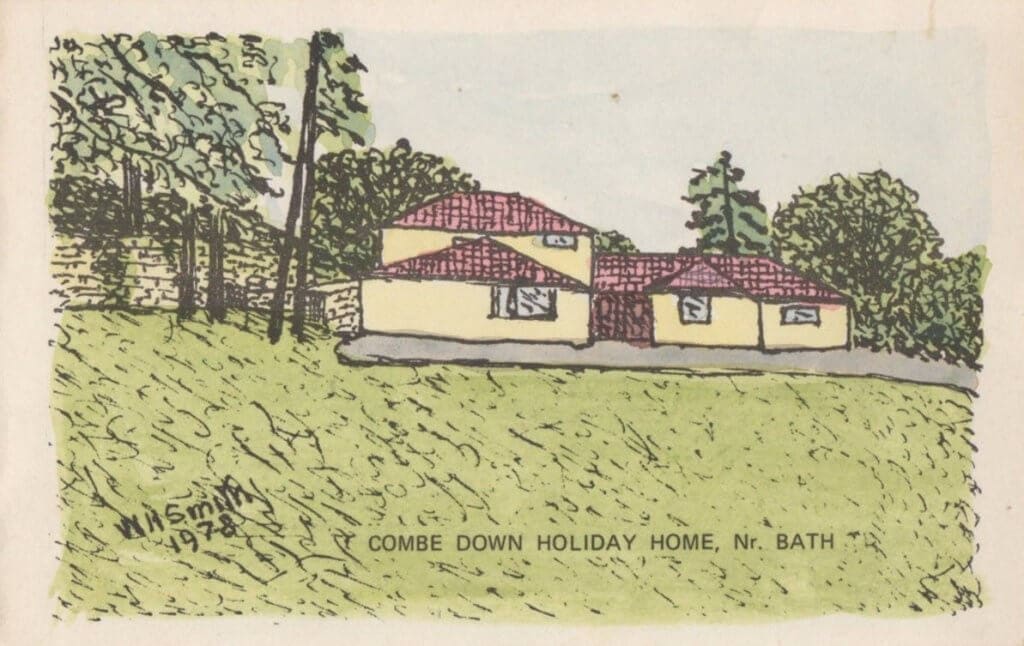

In the 1960s Bath Association for Disabled People were looking for somewhere to buy so that they could offer respite to carers and holidays for the disabled. They bought Combe Down Convalescent Home from the RAF and set up Combe Down Holiday Home for the Disabled.

It was not a great place to bring the disabled being a 3 storey Victorian building with doors that were too narrow for wheelchair access. The building burnt down in 1971.

Luckily it was insured and Dr Sandy Neill and like minded colleagues ensured that a modern building with all the necessary facilities for disabled access atc was built.

It had about 20 rooms and provided excellent holiday/respite care.

The home operated with success for 20 years, but changes in Local Government funding and increasing costs forced the Trustees to review the management of the home.

By the 1990s they decided to sell the home and invest the proceeds and seek a different role based on the holiday/respite care principle.

In 1993 the Trust was reconstituted as Combe Down Holiday Trust with the sole aim of providing holidays, short breaks and respite care for disabled people and/or their carers who live within the Bath & North East Somerset area.

The site was sold for development in 1996.

In 1999 Linden Homes built Quad Villas on the site.

Waterworks

Combe Down Waterworks

Most people used shared wells with the well shafts passing through quarries below. The water from wells was often boiled first for use as drinking water. People also collected rainwater from their gutters, collecting it into a tank for domestic use, though not as drinking water.

Harry Patch says that:

“Apart from the wells, there were two iron water butts in Combe Down fed from the mains. When a handle was turned on the side of the butt a chain ran down over a pulley and opened a stopcock at the base, bringing water out of an ornamental lion’s mouth. One butt was just outside the church, the other opposite the pub, the Wheelwright Arms. If you didn’t have access to a well in the garden, you could draw water from there. Behind both butts was a wooden trough into which water was poured for horses to drink from.”[38]

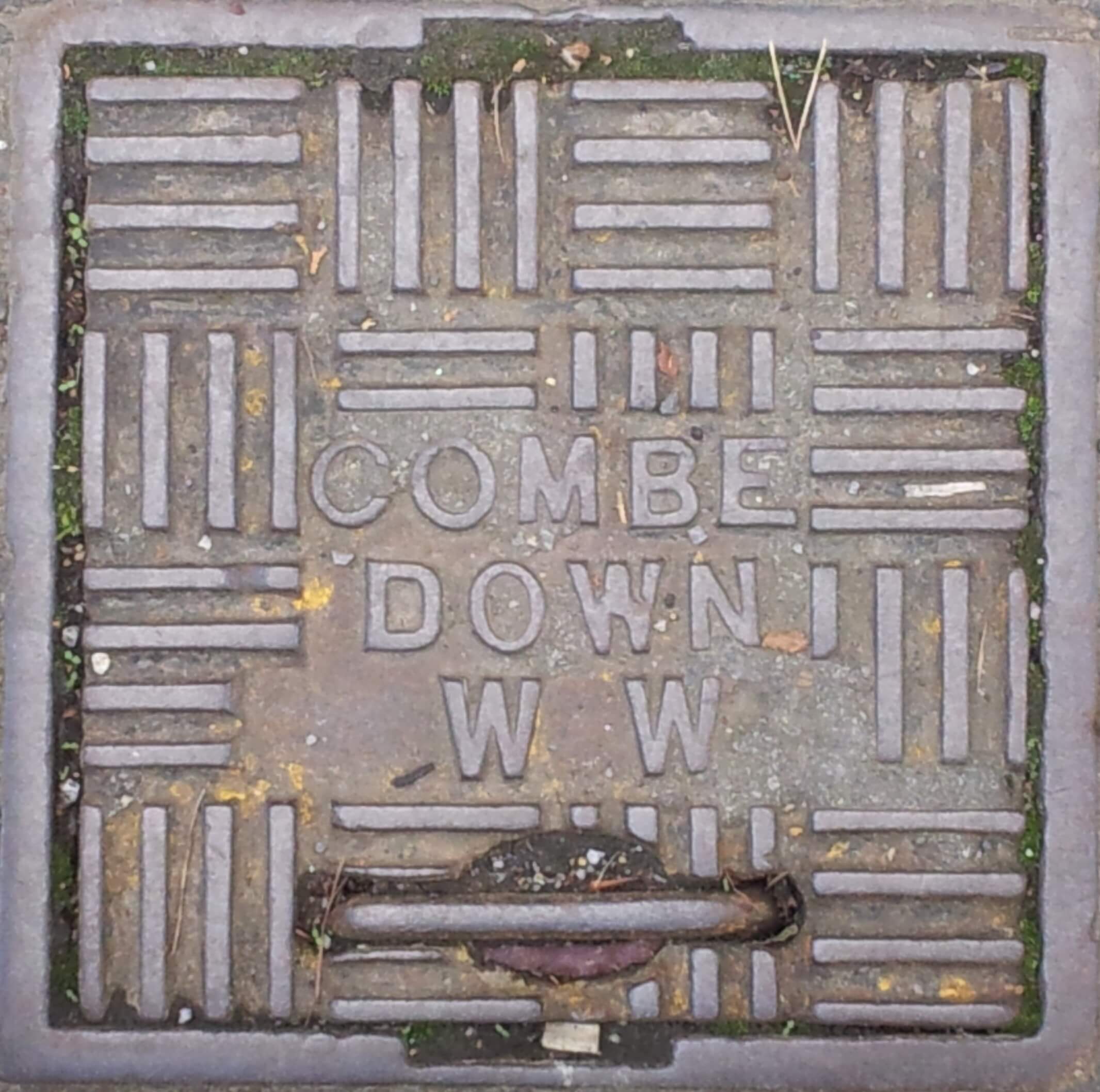

The mains supply was from the Combe Down (Bath) and General Waterworks Company.

It had a forerunner, the Bath and District High Level Waterworks Company which had been set up in 1887 after the death of the Right Reverend Monsignor Dr. Charles Parfitt (1816 – 1886) of Midford Castle who had set up the original waterworks at Midford Springs.

Dr. Parfitt had inherited Midford Castle from Mrs. Jane Conolly (1798 – 1871), the widow of Mr. Charles Thomas Conolly (1791 – 1850) who was the son of Charles Conolly (d.1828) who had bought Midford and funded William Smith’s quarry.

Soon after taking over Dr. Parfitt started the Combe Down and District Waterworks to take water from the Midford Springs. The water was pumped by a water wheel using the water from the Whittaker springs to carry water from the Midford sands.[39]

He was soon supplying the Workhouse and Bath Town Council considered buying the waterworks.[40]

By 1883 the Rural District Council were informed that:

“Combe Down is also more largely supplied from Dr. Parfitt’s private source and many of the wells in the neighbourhood have been closed.”[41]

By February 1886 Bath Town Council had agreed to buy Combe Down and District Waterworks.[42]

A new main from Tucking mill to Entry Hill was laid,[43] and the water supply turned on.[44] #

Storage was by the Combe Down elevated tank standing opposite what is, now, the Forester & Flower. It was a cast iron tank on 8 cast iron legs with a capacity of 40,000 gallons with a roof of iron sheets.[45]

However, Dr. Parfitt became unwell and died in June before the agreement to purchase the waterworks could be completed.

When Dr. Parfitt died his trustees did not want to continue managing the waterworks[46] and a new joint stock company, the Bath and District High Level Waterworks Company Ltd., was incorporated with a capital of £20,000 in shares of £10 each.

In 1890 the Hampton Down reservoir was constructed on land leased for 99 years. It was a stone structure approximately 61’ by 20’ 6” with a capacity of 100,000 gallons.[47] The Bath and District High Level Waterworks Company Ltd. ran until 1901 but was then put into receivership.

Once again the council considered buying the waterworks but decided not to do so.[48] However in 1902 they reconsidered and took powers to purchase the concern.[49]

It was not to be. The receiver put the business up for sale as a going concern. It was bought for £7,000[50] along with the Somerset Coal Canal, which had fallen into disuse and disrepair and had complaints of being in an “insanitary state”.[51]

By 1902 a liquidator for the Somerset Coal Canal Company had been appointed.[52] The canal, as well as being an asset in its own right was to be used to supply more water to the Combe Down Waterworks Company.[53] He sold the coal canal soon after though to the GWR for their Camerton and Limpley Stoke line.[54]

Both businesses were bought by Edward Herbert Bayldon D.L., J.P. (1854 – 1912), who was High Sherriff of Devon in 1905.[55] He had interests in South African gold mines before turning his attention to Dartmoor tin mines in the late 1890s.[56]

He soon gained agreements with Bath Corporation to supply water to areas the council could not as the council was in short supply of water.[57]

In 1906 a 6” main was laid from Tucking Mill to Hampton Down.[58]

From about 1905 there was a move to close wells due to poor water quality and by 1928 the Combe Down (Bath) and General Waterworks Company Ltd. supplied 337 of the 440 houses in the parish of Monkton Combe with 53 being supplied by the Rural District Council.[59] Presumably the other 50 were still relying on wells etc.

The Hayeswood Reservoir was constructed in 1927. It was a reinforced concrete covered tank with 8’ thick walls and a 37’ diameter and held 100,000 gallons.[60]

By the 1950s the staff included a chief inspector and 3 shift workers and was pumping 268,000 gallons per day.[61]

In 1954 the Bath Corporation Water Order, under the Water Act 1945, transferred Combe Down Waterworks to Bath Corporation.

Under the Water Act 1973, the Wessex Water Authority was created in 1974. In 1989 the water boards were privatised and in May 2002 YTL Power International of Kuala Lumpur acquired Wessex Water and hence the waterworks at Tucking Mill etc.

Hospital

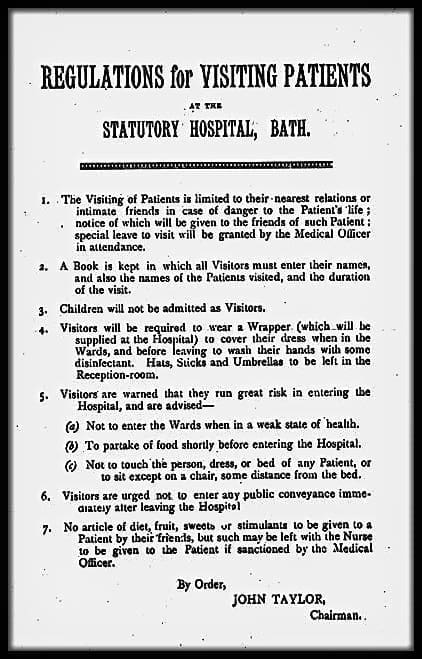

Bath Statutory Hospital

Many towns had some form of isolation hospital from the eighteenth century, usually a ‘pest house’, where infectious people were treated.

It was not, however, until the late nineteenth century that the formal treatment of infectious diseases, such as scarlet fever, typhoid, diphtheria, measles, tuberculosis and smallpox, was considered.

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1868 dealt briefly with the subject, since most patients with infectious diseases found their way into the workhouse infirmaries because voluntary hospitals could and did refuse to admit them.

The Public Health Act 1875 enabled any local authority to provide hospital accommodation for the treatment of patients with infectious diseases paid for by the rates.

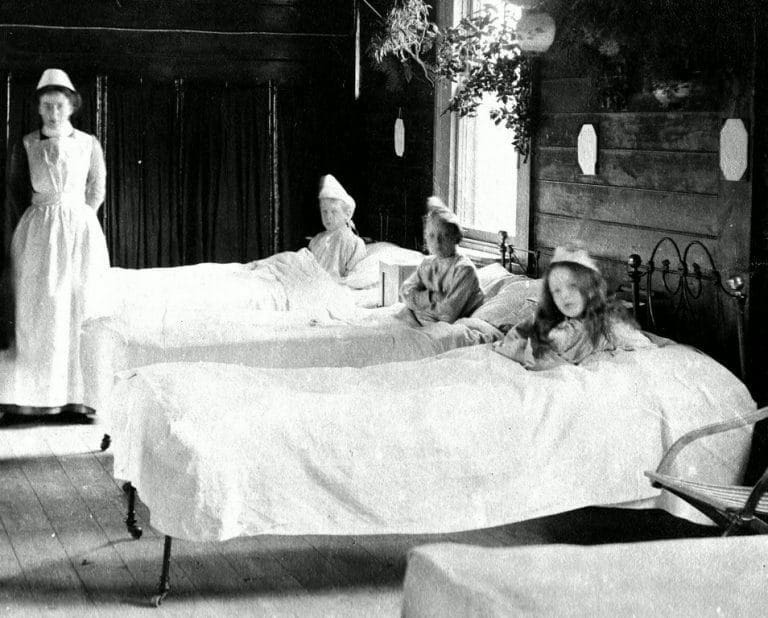

In 1877 the Bath Statutory Hospital was established at the corner of Brassknocker Hill. By 1880 it was being used, along with the Workhouse Union Hospital, to cover a smallpox outbreak and taking 21 cases [62]

The hospital occupied a site of about 8 acres near the top of Brassknocker Hill. A house and a gardener’s cottage were purchased in 1876. The first patient was admitted in October 1876 suffering from scarlet fever. Two small and two large wooden pavilions were added on the south side of the house providing a total hospital accommodation for 70 patients together and some resident staff. By 1877 it had three large wooden blocks for patients, an administration block, a small discharging block, a laundry and a cottage.[63]

In 1930 work started on a new hospital in two phases. In 1931 the new hospital was first used and in 1932 the new purpose built hospital was officially opened on the site as the old hospital had:

“woodwork that was seen to be perishing and...lighting…of a very inferior order…Fifty years ago they were expected as a temporary expedient by Mr. Charles Wibley. They were erected in a panic, and in a piecemeal and temporary fashion, and the amazing thing is that the hospital has done such good work over such a long period.”[64]

The second stage was opened in 1934.

In the early days, admissions were largely for cases of scarlet fever and diphtheria. Between 1895 and 1899, there was annual average admission rate of 137 of which 78% were patients with scarlet fever and 22% diphtheria. Only 7 out of 137 were for other conditions, for example smallpox. Before 1900, many doctors did not always insist on admission of infectious cases to the hospital but attitudes changed in the early twentieth century. Between 1895 and 1900, only 41% of known diphtheria cases were admitted whereas between 1940 and 1945, 97% were removed from home to hospital.

The development of antibiotics – sulphonamides became available in 1935, penicillin in 1944 and streptomycin in 1947 – led to the closure of many isolation hospitals soon after the Second World War but the Bath Statutory Hospital was taken over by the NHS in 1948 and renamed Claverton Down Hospital. For some years it continued in its role as an infectious diseases hospital and treated many children with polio during the epidemics of the early post war years. The hospital purchased a number of Drinker respirators, popularly known as iron lungs. After the introduction of polio vaccination, there were no further cases fell the artificial respirators were removed.

Bath Statutory Hospital became associated more with chest infections and convalescence and closed in 1986. The site lay derelict until 1997 when Wessex Water acquired the site.

Monkton Mill

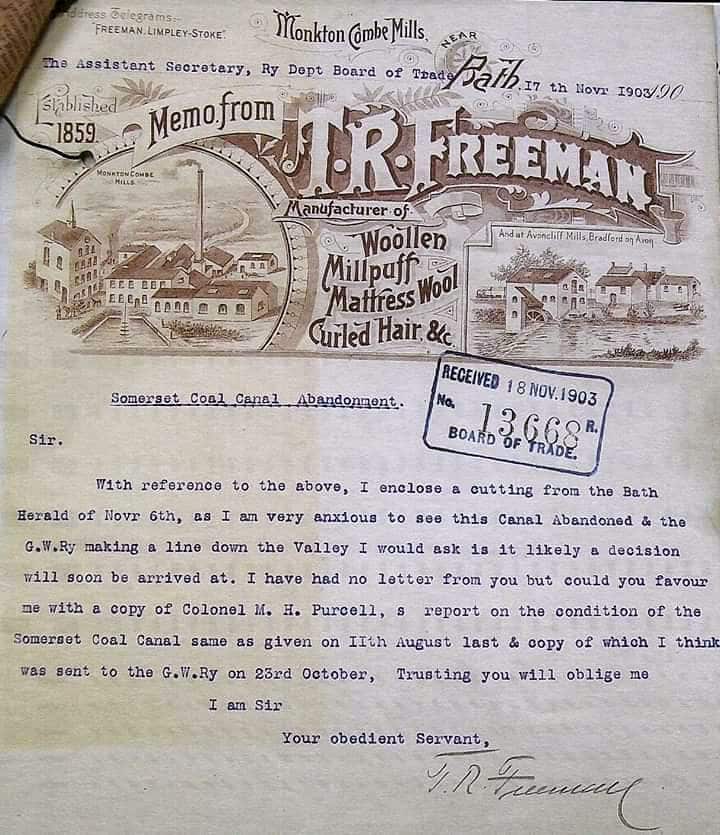

Monkton Combe Mill

Monkton Combe has two mills listed in the Domesday Book – Monkton Combe Mill and Tucking Mill. Beside the Midford Brook there are sluice gates and a millpond for the Monkton Combe mill.

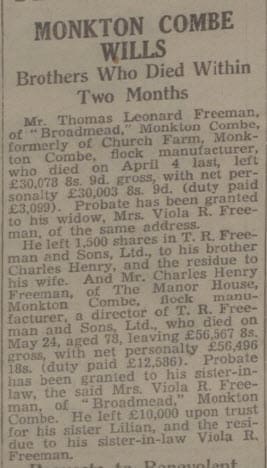

From at least 1884[67a] it was owned by the Freeman family, who also had mills at Freshford and Avoncliff.

It was run by Thomas Richard Freeman (1860 – 1920) and later his sons Charles Henry (1889 – 1947) and Thomas Leonard (1892 – 1947).

The Freshford and Avoncliff mills were run by his brother William Osbourne Freeman (1855 – 1913), who seems to have been a poor business man as he was bankrupted in 1897, owing his brother and his brother’s wife – Sarah Ann Mountstevens (1860 – 1947) – £700 between them as well as loans from a money lender at 40%[67b].

The mill at Monkton Combe was by the station and used the railways to to import the raw material of old clothes from the rag and bone trade.

This was turned into flock, from the Latin floccus meaning lock or tuft of wool, for use in the upholstery trade stuffing mattresses, sofas, pillows, bolsters and other furniture items.

Water power drove the turbine operating the “devils” which broke up the rags.

Reports to The Local Government Board Reports on Rag-Flock, HMSO, 1910 describes the process: