A brief history of stone

it’s reasonably well known that 18th century Bath was with the best stone from Ralph Allen’s Combe Down quarries.

Throughout history we have used stone in a wide variety of ways, we have gathered, quarried, cut, crushed and carved it and an appreciation of stone’s usefulness based on durability or colour is evident from earliest times.

In prehistoric times hard stones provided durable primitive tools and rough shelters were built from stone slabs.

Stones were arranged to create places of worship or burial and mark the site of important meeting places.

The earliest use of stone in the UK was as primitive stone tools or weapons, such as quern stones, sharpening stones, stone hand axes, spear and arrowheads, are common artefacts in many archaeological sites. Housing could be in caves or stone built shelters.

The Romans were probably the first to use sophisticated quarrying methods to obtain stone for building. Many Roman villas, towns and forts were built with stone. The Romans brought quarrying skills, already developed from a long experience of working stone in the rest of their empire, some of which are still used in todays’ quarries. They were among the earliest builders to use ashlar or cut stone blocks for their more important structures.

The Romans were followed in the late 6th century by the Anglo-Saxons and, in the North, the Vikings who used wood for much of their building but were aware of the usefulness of stone. With the spread of Christianity, they began to use stone more widely, particularly in their churches. Surviving Anglo-Saxons stone crosses and monuments show their skill as stone carvers.

The Norman invasion in the 11th century brought a resurgence in stone building and marked the beginning of a period during which many of our most splendid stone buildings were constructed. Many quarries were owned by the Crown.

The Normans’ influence is evident from the incorporation of many familiar building and architectural terms from old French into English e.g.

- aiseler – ashlar – plank

- mason – maçon – builder

- slate – esclat – split

At first the Normans preferred to import the stone with which they were most familiar such as Middle Jurassic limestone from the Boulogne and Caen quarries used in the White Tower of The Tower of London. However, they also began to exploit a wide variety of local stones for castles and other building projects such as the cathedrals at Canterbury, Durham, Lincoln and Winchester.

This building boom continued during the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Edward I constructed a series of massive castles across North Wales. The scale of this programme was so great, and the number of masons conscripted to work in it so large (400 at Beaumaris alone), that it must have disrupted royal building programmes elsewhere for some considerable time.

During the early 15th century many of England’s most ornate churches were built using the profits of its thriving wool trade as patronage for the building of such new parish churches evidently ensured salvation.

Not every English King, was interested in building on such a grand scale. In 1538 the reformation led to the dissolution of monasteries and the sale of their buildings and estates to Henry VIII’s court favourites or to the highest bidder. This allowed many of the growing class of wealthy entrepreneurs to purchase grand houses and become part of a new aristocracy. Some of our most spectacular stone buildings demolished by their new owners. For many decades the monasteries became ‘quarries’ as their stone and other building materials were robbed for use elsewhere.

The right to quarry stone was still under the control of the Crown into the early 17th century and the large-scale use of stone for building was restricted to major royal or church projects. The future of the Portland Stone Quarries was established by the rebuilding of London following the Great Fire of London in 1666. It also led to other towns enforcing the use of stone for building and roofing to prevent such calamities in their overcrowded, timber-framed, urban centres.

During the 17th century the continued rise of prosperous yeomen and the growth of merchant and professional classes led to the building of many more new stone ‘manor houses’.

From the early 18th to the mid-19th century the gathering pace of industrial revolution, the growth of new industries and their associated and expanding rural and urban populations, all needing houses and places of work, allowed the stone quarrying industry to expand.

Ralph Allen, developed and expanded the Bath stone quarries at Combe Down which began to compete directly with the Crown controlled Portland Quarries in the London market by taking advantage of the fast-growing canal network.

Quarrying now became a major industry in many other parts of the country, particularly, around the embryonic industrial centres of the midlands and north.

The Victorian period saw a massive expansion of industrial and urban centres particularly in the north of England. Victorian architects selected and used British building stones to great and colourful effect, despite competition from the increasingly mechanised and developing brick industry and other materials such as terracotta and faience, whose glazed surfaces were considered more resistant to atmospheric pollution. Confident and newly wealthy city councils determined that their most important civic buildings should be built of natural stone and on a grand scale.

The durability of stone was also appreciated for large scale engineering projects. Many reservoirs were constructed to supply water to the new urban and industrial centres and stone was commonly chosen for the facing.

On a more sombre note, stone has always had a special place in our culture regarding burial sites. In earliest times the durability of stone usually meant that the most important burials used stone coffins, niches cut into stone bedrock or were marked by stone monuments. As our society has developed we have held on to this notion and to many people the selection of an attractive and durable headstone is still a very important family ritual.

Perhaps the most poignant use of stone must be order for 120,000 gravestones for those soldiers who fell in the 1st World War Similar orders were also filled from the Bath and Portland quarries for the dead of the 2nd World War.

Today, new stone buildings have become something of a rarity. Instead of the load-bearing block stone the demand is now for flawless thinly slabbed stone which can be used to clad core structures of concrete and steel. These slabs must meet increasingly tight testing specifications and need to demonstrate very different strength and durability parameters to traditional building stones.

About Combe Down Stone

Combe Down’s freestone is why it exists. Freestone is a fine grained stone which can be cut easily in any direction without shattering or splitting. It is traditionally used as building stone in the region and many other cities in the UK, and has good resistance to weathering.

Combe Down stone is is a Bath Stone and an oolitic limestone. Combe Down limestone is formed from grains of calcium carbonate laid down during the Jurassic period (201 to 145 million years ago) when the region was under a shallow sea. It is classified as part of the Great Oolite Group of the Chalfield Oolite Formation of which the Bath Oolite and the Combe Down Oolite are members. These are the Bathonian Series of rocks. The beds are part of the Great Oolite, of the middle Jurassic age, laid down in a shallow sea about 168.3 million to 166.1 million million years ago.

Combe Down stone was formed when layers of marine sediment (rock and soil particles, remains of marine organisms, products of submarine volcanism, chemical precipitates from seawater) were deposited. The tiny individual spherical grains, or ooliths, were coated with lime as they rolled around the sea bed and, later, formed sedimentary rocks. Oolitic comes from the Greek òoion meaning egg and líthos meaning stone. Under the microscope, the ooliths are formed from ooids, with a diameter 0.25 – 2 mm, in concentric layers, that look like fish eggs.

The stratigraphic unit (or layer) below the Twinhoe Beds of the Great Oolite which form the uppermost part of the Combe Down plateau is the Combe Down Oolite which contained the mined stone.

The top 1.5 to 2m of the Combe Down Oolite consists of a buff, thinly to medium bedded, fine grained, slightly oolitic limestone with abundant shell debris. This stone is stronger, more thinly bedded and has a different fracture pattern than the worked freestone. It is probably for these reasons that the old miners referred to it as the ‘Bastard Stone’ and it was left by them to form the roof beds over much of the quarries.

The worked stone of the Combe Down Oolite is up to 9m in thickness and consists of a buff, medium or thickly bedded oolitic limestone. Although some cross bedding is known to exist in Springfield quarry, the medium to thickly bedded strata in the Firs and Byfield mines do not show this phenomenon. Beneath the worked stone of the Combe Down Oolite is 2 to 3m of pale buff / grey, thinly bedded, crystalline, shelly, oolitic limestone of the Lower Ragstone (the lowest unit of the Great Oolite). Due to the greater strength and variable character of this limestone it was not extracted by the old quarrymen.

Two prominent fracture sets in the Jurassic rocks in the Bath area could be clearly seen in the roof of the underground quarries at Combe Down where stone was extracted by the “room and pillar” method, by which chambers were mined, leaving pillars of stone between them to support the roof. When the alignment of these fractures was parallel to the longest part of a mined “room” a large amount of unsupported stone would be left along the fracture, leading to a higher risk of mine roof collapse that led to the need for stabilisation of the Combe Down stone mines between 1999 and 2009.

History of quarrying Combe Down stone

Bath stone was used by the Romans, who were probably the first to quarry on Combe Down from the 1st to 5th centuries, but, with hundreds of years of quarrying at the same sites, all evidence of earlier workings has been lost and there are no written accounts.

The Anglo-Saxons built mostly in wood though in the 7th century Osric founded the first Abbey in Bath. The Anglo-Saxons had a ready supply of material left from the Roman era and even today some Roman stone is still visible in Bath Abbey. A later Abbey was built and used for the coronation of Edgar in 973, but this was demolished in 1088. Whether any of these buildings used Combe Down stone is unknown.

The second Abbey was replaced by a Norman Abbey, which, in turn, was replaced by the present Abbey around 1499 – although building work continued for another 200 years.

Leland visited the area in 1542 and tells us that, after crossing the Midford Brook by a bridge at Monkton Combe, he went: “to Bath 2. good miles al by mountayne ground and quarre” which seems to refer to opencast quarrying.

In July 1663 the Danish scholar Ole Borch visited Bath and Wookey Hole. His book of 1680 includes the passage:

"In Anglia ergo ad Balhoniutn oppidum thermis Bladudianis celebre, in monte vicino spelunea se aperit, ab incolis loci ad saxa aedifitiorum escauata, in qua aqua pedetentim defluetus in marmor subilaulultn cernitur."

which may be translated:

"In England, therefore, near the town of Bath, famous for Bladud's hot springs, a cave opens on a nearby hill, hollowed by those who live in the place for stone for buildings, in Which the Water, drop by drop, is to solidify into a yellowish marble."

The next reference to mining is by John Wood the Elder who writes of the “Antient Free Stone Quarries” and that: “Those Quarries were subterraneous caverns from time to time dug in the Brow or the Mountain” and that: “Accidents frequently happening in the Old Subterraneous Quarries, Mr. Allen began to dig for Stone in a new Quarry, open from the Top”.

This was where Quarry Vale cottages now stand and was worked out by about 1800.

Ralph Allen

Ralph Allen (1694 – 1764) is justly famous for making the stone famous and for starting large scale commercial use of Combe Down and Bath stone.

Ralph Allen had moved to Bath in 1710, and after making profits working as postmaster, began to acquire land in Combe Down in 1726. By 1731, he held a monopoly over the quarries and set to increase the output of Bath stone. By 1744 he owned the entire area and, with architect John Wood, had planned and put into effect a complete rebuilding of Bath using Bath stone, the best source of which was on Combe Down. His legacy has had a tremendous impact on the character of Combe Down as well as contributing to the development of Bath and the use of Bath stone for building all over England.

Ralph Allen transformed the landscape with his quarrying activities, building a tramway to transport the stone from Combe Down to the River Avon along what is now Ralph Allen Drive.

Dr Richard Pococke, on his trip to Bath, visited “the quarries to the south-east” in 1750. These are likely to have been the Combe Down quarries and he notes that there were several of them. He appears to be referring to opencast quarries and makes no mention or mines. He gives a geological section showing that about 12 feet of freestone was worked beneath 18 feet of overburden.

"...Another day I made an excursion to the quarries to the south-east, there are several of them at the top of the hill; examining the strata, there is first about a foot of earth, then a stratum of lime stone about 4 feet deep which seemed to be full of very small shells, the exact form of which are not discernible to the naked eye, but with a microscope some curious observations might be made on this and the other strata. The second stratum, two feet deep, is what they call strigery, it seems beside the other stone a mixture of spar. The third is pitching stone with which they pitch the streets, it is a composition of spar and of small nodules like the small pea of a fish. The fourth they call rag-stone is of the same kind but has more spar in it, and they saw it for paving, this is four feet thick. The fifth is picking bed five feet thick, of the same appearance only has less of spar; it is softer than the free-stone they work and will not stand the weather. Then follow the several beds which they work from two feet to four feet thick; they say there is good stone 30 feet deeper than they work, and I suppose they at present work 12 feet below the picking bed in all about 30 feet, and lately in digging a well here they came to gravel, after digging about 70 feet..."

Ralph Allen died in 1764 and the tramway was broken up and sold off for scrap in the same year. Quarrymen now had to lease the mining rights for the relatively small plots of land that they worked.

The stone was transported by horse and cart, a slow process, until 1773 when a turnpike act encouraged the building of new, surfaced roads.

Tollgates were installed at both ends of Combe Down, at the top of Brassknocker Hill, and at the Bradford Road junction with Combe Road when the Bradford Road was improved, at which time all users were required to pay a fee towards the cost of construction and maintenance, often based on weight of load.

Unlike the shepherds who circumvented the toll-gates by leading their flocks along Shepherds Walk to the south of the village, the quarry masters had no choice but to pay to transport their stone along the turnpike.

Viscount Hawarden

Ralph Allen’s estate eventually passed to the 1st Viscount Hawarden who took no active interest in the quarries, but was happy to rent them out. By the end of the 18th century the South facing slopes of Combe Down were seen as an ideal spot for convalescing after taking the waters in Bath. The 1st Viscount Hawarden converted Ralph Allen’s former quarrymen’s cottages into lodgings for this purpose.

The 1st Viscount Hawarden died indebted in 1803 and his son began to sell of the estate to pay his debts.

Lewisham Records office had a number of documents that show these transactions:

Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/83 15 May 1804. 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Edward Layton Esq. Samuel Pearce. Consideration: £3 13s 6d per perch p.1/2 a. Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/84 15 May 1804. 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Edward Layton Esq. Richard Lankesheer. Consideration: £3 13s 6d per perch p.1/2 a. Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/85 22 Nov. 1804. 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Edward Layton Esq. John Greenway.Consideration: £3 13s 6d per perch p.1/2 a. Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/86 24 Sept. 1808. 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Nathaniel Hadley Esq. John Greenway. Consideration: £3 13s 6d per perch p.1/2 a. Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/87 24 Sept. 1808. 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Nathaniel Hadley Esq. Isaac Sumsion. Consideration: £3 13s 6d per perch p.1/2 a. Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/88 29 March 1811, 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Nathaniel Hadley Esq. Abraham Sumsion. Consideration: £3 13s 6d per perch p.1/2 a. Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/89 21 Nov. 1816, 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Nathaniel Hadley Esq. Job Salter. Consideration: £3 13s 6d per perch p.1/2 a. Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/90 7 March 1827, 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Nathaniel Hadley Esq. John Davidge. Consideration: £8 16s per perch p.1/2 a. Memorandum of Agreement. A91/18/91 17 Dec. 1856, 1 acre on Coombe Down to be used a quarry. Samuel Hadley Esq. Richard Lankesheer. Consideration: £10 p.a.

The quarry masters

With Thomas Ralph Maude 2nd Viscount Hawarden (1767 – 1807), Mary Allen’s son and Ralph Allen’s great nephew, selling off the estate to help pay his father’s debts, individual quarry masters were, at last, able to purchase the land which had been continuously quarried since Ralph Allen‘s time.

There was a steady influx of skilled migrants from the Corsham/Melksham area as stone production expanded and thus began probably the most productive period of quarrying on Combe Down. A new phase of construction began in the village resulting in many of the older cottages that we see today.

The earliest buildings other than De Montalt Place, which had been built by Ralph Allen for his quarrymen, were built between 1805 and 1820 and many such as Brunswick Place were the homes of the quarry masters.

Many of the surnames of the quarry masters are well known on Combe Down. The Nowell family were perhaps one of the best known quarry masters. They took their stone from a surface quarry into the rock outcrop itself, following the line above Shepherds Walk. Their fame and fortune became assured not by quarrying as such, but by one of the younger sons, Philip, who became a master mason.

By the time he died, in 1853, Philip Nowell‘s legacy included the building of not only the older part of Rock Hall we see today, but also major extensions to Longleat, seat of the Marquess of Bath, Windsor Castle then home to King William IV and Apsley House, the official residence in London to the Duke of Wellington.

He became one of the best known and possibly most trusted builders in the land. Being responsible for purchasing the Bath stone required for these and many other projects, he naturally turned to his family quarry and those of his neighbours for supply. Meanwhile transportation of the stone had been made easier by the opening of the Kennet and Avon Canal in 1810.

Underground evidence suggests that by 1840 most of the stone had been quarried and the coming of the railways led to newly discovered workings at Box and Corsham to provide an alternative source of supply.

The decline

With the rise of the quarries at Box and Corsham the people of Combe Down could no longer depend on quarrying and had to look for alternative livelihoods. The practice of coming to Combe Down to convalesce after illness was revived as the quarrying declined and a small construction boom began for large detached villas for the upper middle classes along Church Road and Belmont.

But, though less was quarried, Combe Down stone was still recognised as of superior quality. According to Horace Bolingbroke Woodward in 1876:

"In regard to the qualities of the Great Oolite, the best stone for weathering is considered to be that at Combe Down; that of a finer quality and best adapted for interior work is dug at Farley Down. Box Hill yields a stone of a very superior quality, as to fineness of texture, called 'Scallet.'"

Woodward also says that:

"According to E. Owen, who wrote in 1754, and whose remarks I may quote, ‘there is no stone that differs so much in its bed, and after it has been wrought and exposed to the air, as the Bath freestone. While it is in the ground, it is soft, moist, yellowish, and almost crumbly; and it seems very little more than congealed sand, and that not well concreted together. But when it has been some time exposed to the air, and is thoroughly dry'd, it becomes white, hard, firm, and an excellent stone’”.

Up until 1887 most of the quarries were independently owned; frequently the quarry master rented the quarry from the owner and was an entrepreneur. Some, like Philip Nowell, made a lot of money and became famous.

With the opening of larger mines near Box, the coming of the railways, and the fact that many Combe Down quarries had been worked out of commercially viable stone, things became harder. So, on 1st January 1888, seven firms joined together to become the Bath Stone Firms Ltd. (The Corsham Bath Stone Company Limited, R. J. Marsh and Company Limited, Samuel Rowe Noble, Pictor and Sons, Stone Brothers Limited, Isaac Sumsion and Randell Saunders and Company Limited). [1]

In 1889 the Bath Stone Firms took over Portland Quarries. On 27th December 1897 the Bath Stone Firms Ltd. became the Bath and Portland Stone Firms Ltd [2] In 1908 Bath and Portland Stone was formed from the Bath Stone Firms. [3] The Portland side of the business was separated from the Bath side in 2004 and became Stone Firms Ltd. Both were then owned by Hanson Bath and Portland Stone, part of Hanson PLC. [4]

One firm that remained independent was Hancock. John Hancock & Sons has, in 2014, the only Combe Down quarry still in operation.

Although quarrying fell into decline after 1840, it continued in some parts of Combe Down, particularly on the north side of Bradford Road, until well into the 20th century. In 1895 The Builder listed 10 open quarries and one mine on Combe Down. Upper Lawn Quarry, across the fields from Gladstone Road, continues to operate today, the last quarry on Combe Down.

The Stabilisation

Two centuries of excavation of Bath stone left a huge void under the original parts of Combe Down village. Pillars left by the old miners for the stability of the quarries had degenerated and collapses of the layer between mine and buildings occurred.

In January 1993 the tenants of two council properties in Westerleigh Road were moved out due to fears for their safety.

In one of the largest U.K. Local Government civil engineering projects, Bath & North East Somerset Council together with their private sector partners (Davis Langdon, Hydrock, Provelio, Scott Wilson Mining and others) did extensive investigation and feasibility analyses before filling the mine with foamed concrete – rather than the pulverised fuel ash that had been proposed in a 1990s suggestion leaving galleries for rare bat species.

The infilling project lasted for 10 years from 1999 until 2009, covered 25.608 hectares, and affected 649 properties that were stabilised, most domestic homes. The total volume of infill placed was 620,894 cubic metres, enough to cover a football pitch to a depth of nearly 90m. 590,894 cubic metres of foamed concrete, plus 30,000 cubic metres of stone were placed into the quarries.

The Archaeology Data Service has a repository of Oxford Archaeology‘s documentation for the project.

Combe Down Mines History 2005 from Quest 2012 on Vimeo.

List of Combe Down Quarries

Map of Combe Down quarry and landmark locations

This list runs, roughly, from East to West.

Union Quarry

Opposite St Martin’s Hospital, it was in use before 1904 and was still working the West face in 1958. It is now lost and built over. It was worked by Shellard and Son before WW1, then by the Hill brothers between the two world wars and finally by Bill Reed until the mid 1960s.[5]

Crossway Quarry

Closed in 1904 and completely backfilled. The Western one of about 7 acres is said to have been used to dump rubble from the 1942 air raids. There is a playing field there now. On the Eastern one stands the Catholic Church of St Peter & St Paul.[6] The Eastern quarry of about 5 acres was worked by James Sheppard from at least 1833[7] and by Thomas Sheppard (presumably his son) from before 1863[8] until 1881 when his lease expired and he sold his stock in trade.[9] It was up for sale again in 1896.[10]

Entry Hill Quarry

This was being worked from at least 1776 as James Clapp the quarry master was killed by a ‘falling in’ that June.[11] In 1835 it was being worked by James Sheppard who also mastered Crossway Quarry.[12] In 1913 it was being worked by F. C. Tipper.[13]

According to Peter Addison it was briefly reopened in the 1940s.[14] It has since been a council storage depot.[15]

Shepherd’s Walk Quarry

Between Shepherd’s Walk and Southstoke Road. This was shown as No 4 on the map in the April 13th 1895 issue of “The Builder.[16]

Southstoke Lane Quarry

Southstoke Lane was a small quarry which specialised in garden wail stone, vases and ornaments. It is not known if there were underground workings.[17]

Springfield Quarry

Open workings with quite large areas underground. Now landscaped area enclosed and by the quarry walls with the old adit entrances covered by concrete blocks. Access via Entry Hill Park. This was the largest open quarry in Bath. Over its lifetime it yielded c.2.5 million cubic feet of stone. Most of the activity was c.1750 – 1900.[18]

Foxhill Quarry

Beside Foxhill Lane. Closed by 1900.[19]

Greendown or Turnpike Quarries

Mentioned by Peter Addison in Around Combe Down.

Cox’s Vertical Shaft Quarry

A small underground quarry that was worked after 1900 but had closed by the mid 1930s. The now lost and sealed entrance was under the entrance building of the Foxhill’s MOD complex on

Bradford Road.[20] It was owned by the Combe Down (Bath) Freestone Co. Ltd. Formed in 1909 and dissolved in 1931.[21]

Street’s Quarry

Named after Henry Street who bought it from Richard Lankesheer and sold it to Philip Nowell.[22]

Cox’s or Collibee’s Quarry

A large area of open quarry with extensive underground workings.[23]

Byfield Quarry

In Rock Hall Lane near the King William.

Stonehouse Lane Quarry

Between the Combe Down RFC field and Stonehouse Lane was a long linear quarry which was worked until the 1930s.[24]

Hanginglands Quarry

Mentioned by Peter Addison in Around Combe Down.

Stennard’s Quarry

Mentioned by Peter Addison in Around Combe Down. It appears it shut down about 1899.

Allotments Quarry

Behind Westerleigh Road, with Rock Lane to the West.

Davidge’s Bottom Quarry

At the North end of Rock Lane, near an entrance to Firs Quarry. Possibly named after George Davidge, Quarry Master c.1848. Last mined about 1930.

Ralph Allen’s Quarry

Thorpe’s 1742 map indicates Ralph Allen’s quarry had locations opposite Isabella Place and Rock Lane and on The Firs, whilst a drawing by Thomas Robbins indicates immediately opposite De Montalt Place.

Firs Quarry

A large underground quarry ranging from Gladstone Road to the Hadley Arms to Rock Lane and North Road to Church Road. There was a honeycomb of tunnels with headroom of from less than one to about three metres, and some caverns up to about eight metres in height.[25]

Vinegar Down Quarry

Behind Beechwood Road. Closed about 1920.

Love’s Quarry

Mentioned by Peter Addison in Around Combe Down. Mr. Edwin Love had quarries at Combe Down and Odd Down.[26]

Lankesheer’s Quarry

Mentioned by Peter Addison in Around Combe Down.

De Montalt Quarry

Behind De Montalt Place it had access to Firs Quarry. Probably not worked since the 1830s.

Stone’s Quarry

Mentioned by Peter Addison in Around Combe Down.

Junction Quarry

Situated at the top of Ralph Allen Drive on the West. It is suggested that it was worked by Mr. G.C. Mann in the 1860s.[27] G.C. Mann quoted and was awarded the contract for the proposed new police station having, apparently, done good work at The Mineral Water Hospital and Blue Coat School.[28]

He also quoted for the restoration of Bath Abbey[29] and helped to ceremonially lay the foundation to an extension to the hospital.[30]

Upper Lodge Quarry

Behind Upper Lodge on the corner of Ralph Allen Drive and North Road.

Hopecote Quarry

Behind Hopecote Lodge on Church Road. Now a housing estate. The remains of the drift into the Hopecote Quarry and possibly the Firs Quarry run through the kitchen of 121 Church Road, where old timbers are preserved.

Beechwood Quarry

Below Beechwood Road on Summer Lane.

Cruikshank’s Quarry

Between Summer Lane and Belmont Road.

College Quarry

Mentioned by Peter Addison in Around Combe Down.

Plantation Quarry

Mentioned by Peter Addison in Around Combe Down.

Gym Quarry / Prior Park Quarry

Stone used to build the Prior Park gymnasium in 1839:

“Great additions have been made during the past year to the accommodations of the establishment at Prior Park. A matron is attached to the College of St. Peter's, who has care of the younger students, lid of the sick, so that both have now every comfort that can be desired. The playgrounds of St. Peter's comprise, besides the playgrounds of the College, a gymnasium, containing a covered colonnade, 80 feet by 18, a calefactory, a prefect's room, a reading room, a nagged terrace, 80 feet by 18 ; a tennis, or ball court, 80 feet by 100 ; a gravel terrace, 520 by 50 feet;……”[31]

Kingham Quarry

The quarry used by William Smith.

Jackdaw Quarry

The blocked up entrance is still there, close to the road and about 3 metres wide and 1.5 metres high with a stone arch. It is said that stone from Jackdaw and Vinegar Down was used to line some of the Combe Down railway tunnel.

Tea Gardens Quarry

For many years the Rockery tea garden, now a housing estate. Remains of open workings, worked from about 1850, but now turned over to housing.

Rainbow Woods Quarry (Fairy Wood Quarry)

Opposite the Rockery tea gardens, this should more properly be called Fairy Wood.

Hancock’s / Upper Lawn Quarry

Open workings just off Shaft Road and the only working quarry left on Combe Down, operated since 1850 by the Hancock family. This quarry supplies stone for building restoration work, has 30,000 cubic metres of stone, and at the current extraction rate is estimated to have 100 years of supply left.

Mount Pleasant Quarry

East & West quarries; open and underground. Two surface quarries and small underground workings with up to nine entrances in the past.

It was operated in 1871 by Stone Bros.[32] The Eastern part probably closed pre-1914. By 1930 it was operated by Bathite Ltd.

It was completely backfilled in the 1980s to allow playing fields. The Western part of the quarry still exists, disused and closed off pending a decision on what to do with the site.[33]

The Eastern part now has the Oldfield Old Boys RFC club house on it and the playing fields above.

The quarry has not operated since the mid-late 1980s but was connected to Grey Gables Mine in 2006 by Edmund Nuttall Limited for bat conservation.[34]

Lodge Hill Quarry / Shaft Road Quarry

Quite large quarry East of Shaft Road, towards the hill edge passages run very shallow only feet below the surface… Small regular system and there are a number of main galleries like wheel spokes from the entrance.[35] The stone from Lodge Hill was used in the restoration of Henry VII’s Chapel at Westminster (1819).[36] It was owned by Vaughan-Jenkins family, covered an area of c.6.5 acres and closed in about 1935. In 1858 it was being worked by Thos. Shepherd, J. Davidge, J. Sumsion, Henry Stone and J. Vaughan.[37]

St. Winifred’s Quarry

Large open workings with small underground section East of Shaft Road. It was closed in 1938.[38]

Quarrying Bath stone

Stone needs to be carefully removed and prepared for use without causing damage to or weakening of the stone. Initial extraction is still commonly carried out by simple channelling using picks and drills and percussive splitting (plug & feathers) or by sawing of the block from the bed. Extraction by blasting techniques is rarely used in most sedimentary stone quarries.

The strength and durability of stone is affected by many natural factors such as jointing, cleavage, bedding etc. and quarrymen have learned to take full advantage of these factors.

Jointing is a common feature of sedimentary rocks and their bedded nature controls on the size of block which can be produced. The techniques used to initially extract stone blocks have tended to exploit such natural lines of weakness.

Changing techniques in the construction industry have led to different needs for stone, principally since the 1930’s the increasing use of thinly slabbed stone for cladding on prefabricated metal frameworks. Although these demands have necessitated the setting up of new standard tests to ensure the suitability of the many different stones now available to the expanding world market, quarrying production techniques still largely follow traditional techniques changing only in the scale of production.

A quarry face is worked by exploiting naturally occurring lines of weakness in the rocks provided by joints and / or bedding planes. The large blocks produced are then reduced in size by drilling and splitting using iron wedges (‘plug and feathers’) or by saw.

In old opencast quarries the stone was removed from the face with the use of bars. By using the natural faulting, blocks of various sizes could be broken away and then squared. This was not very efficient as large blocks were rare. Later, quarrymen started to follow the beds of stone into the hillside using adits at the same level as the stone outcrops. Bars were still used to break away blocks, but quarrymen started to use the bars to chisel away stone to remove larger blocks. This method was known as jadding, and was in use until the mid-1800’s. Early in the 19th century large saws were introduced underground.

Underground working takes place at relatively shallow depths accessed by adits or by narrow vertical shafts. Underground quarrying relies on the room and pillar method of extraction, where pillars of stone are left in place to support the excavation at the working face. Extensive, interconnecting underground gallery systems can be developed by this method.

Early illustrations of quarrymen show them using a shallow-bladed frame saw very similar to a carpenter’s saw. The frame is in the shape of a squat letter H; the shallow thin blade was fixed between the bottoms of the uprights and tensioned by a twisted cord and stick between the tops of the uprights. Metopes of these can be seen on numbers 11 and 21 The Circus. Hasell’s print of 1798 of an open quarry near Bath shows a quarried block being cut with a frame saw.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, frame saws were used by stone cutters working in the underground Combe Down quarries to cut up quarried block into products such as ashlar and copings. These saws were also sometimes used to cut stone from the rock. The frame saw was cumbersome as the frame and its height made it unsuitable for digging stone underground. However, they were sometimes used where the frame could straddle the stone being cut. In Firs quarry and in one of the Hampton Down quarries there are a few surviving frame saw pillar cuts. The saw marks are distinctive and unlike the ripple marks made by the later frig bob saws, the saw cuts are often concave indicating a shallow blade.

In a few quarries there is evidence mainly in the form of pillar saw cuts that show that one-man, rigid-blade saws were used, albeit as an addition to the prevailing method of digging with wedges and chips, from circa 1810 to circa 1830.

The bulk of these early pillar saw cuts are in the northern part of Byfield quarry; some of these sawn surfaces have dateable graffiti written on them. The following dates have been recorded:

- 1814

- 1818

- September 21 1823

- March 22 1838

- 1840

- 1845

though the graffiti may be much later than the sawing.

The longest saw cut was 5’ 10” (1.78 m) long indicating a saw length of around 7’ (2.1m). Other more typical saw cut lengths are 3’ 9” (1.16m) and 3’ 4” (1m). The latter saw cut exhibited score marks made by the saw teeth when the saw was withdrawn vertically from the saw cut: the pitch of these score marks is 35 mm indicating a blade with widely set teeth at a pitch of 11/16” (17.5 mm).

Similarly, in the adjoining Firs quarry, graffiti dates of:

- Feb 18 1831

- May 19 1841

have been recorded on sawn surfaces. Some of these sawn surfaces show marks that cannot be matched to any known type of saw.

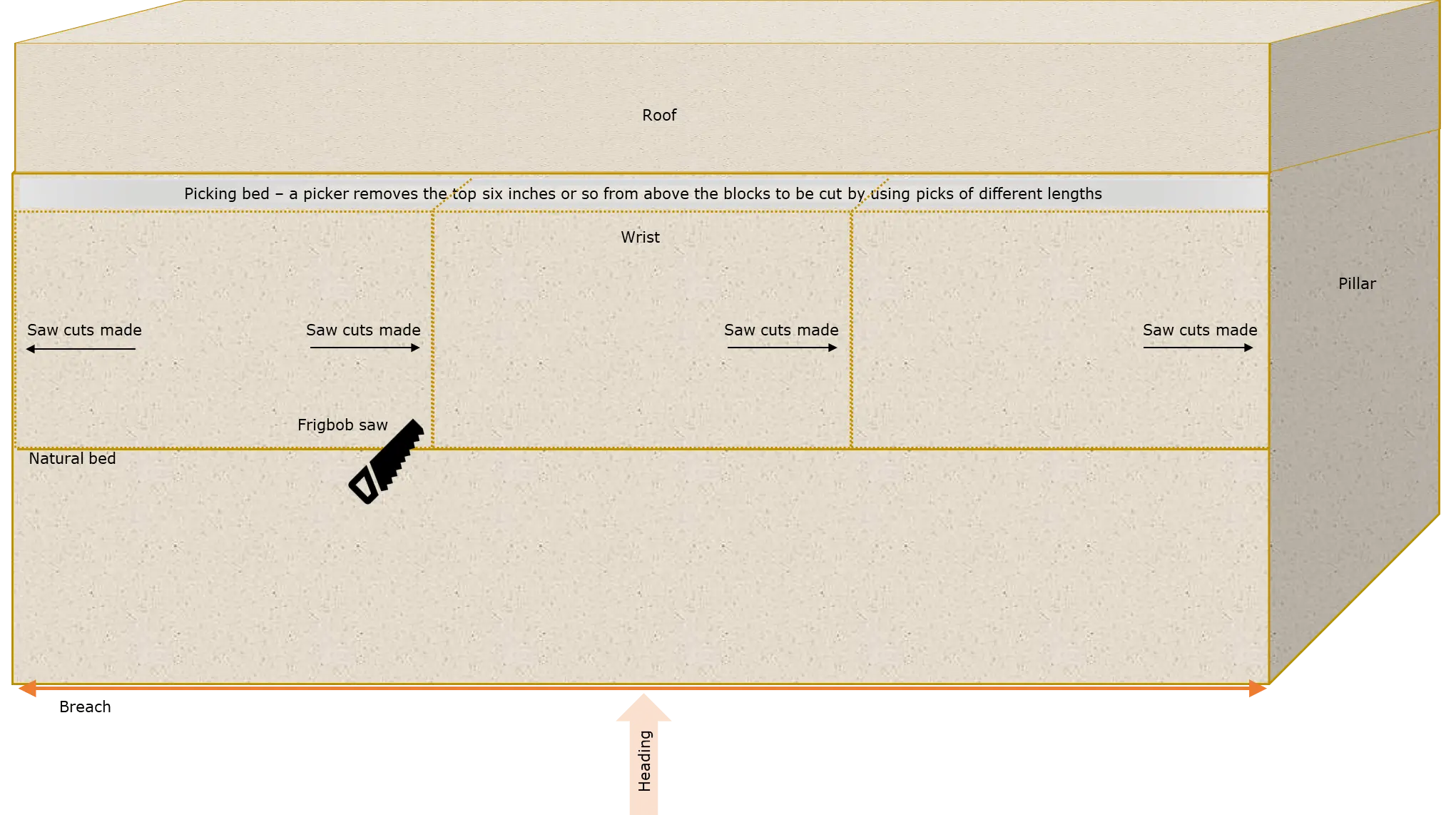

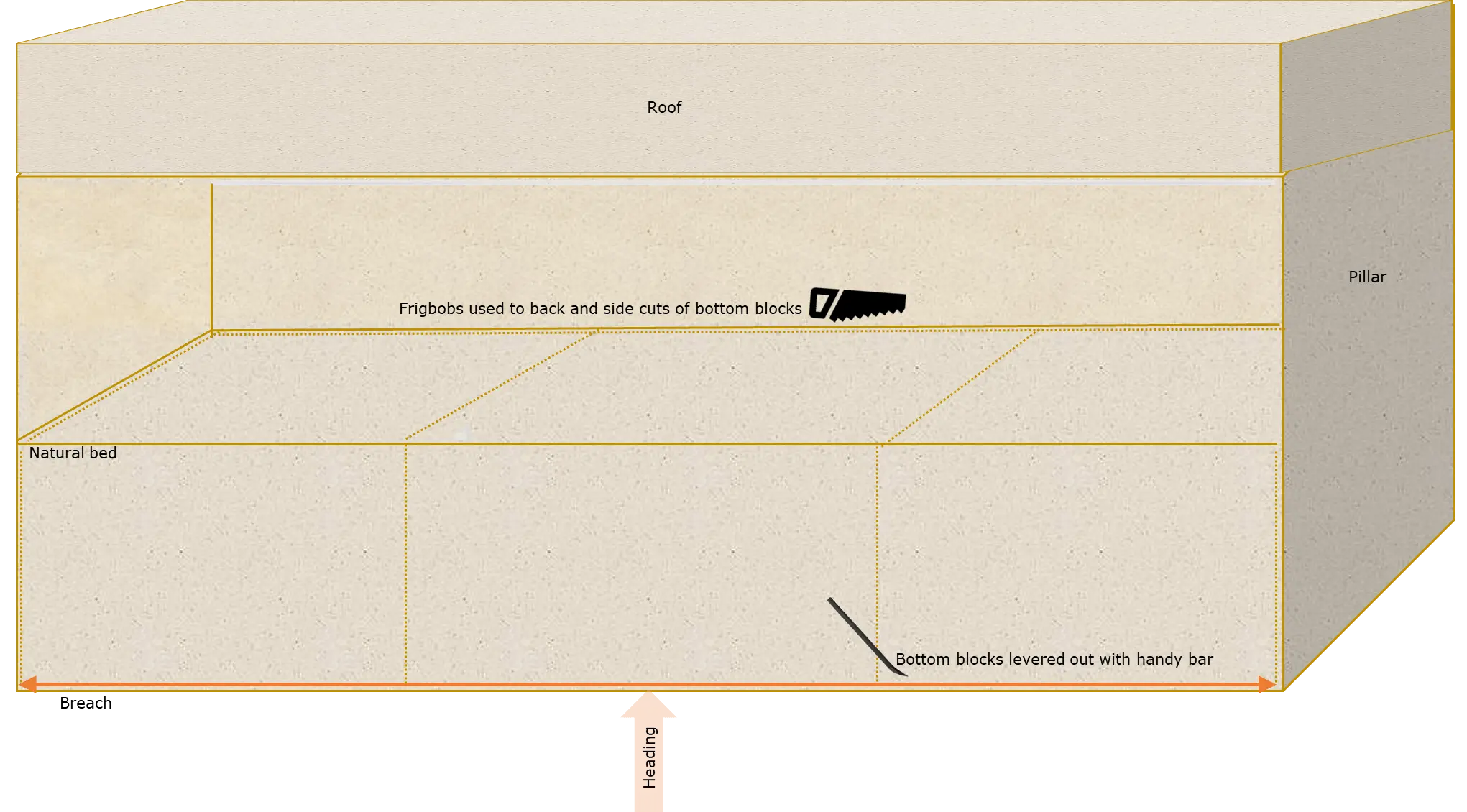

The single-hand stone saw known to quarrymen and masons as a frig bob typically had a heavy rigid blade ranging from 5’ to 7’ (1.5m to 2.1m) long and when new was 9” (225 mm), or more, in depth with a peg tooth profile at a pitch of 5/8” (15.87 mm).

For sawing blind cuts in the rock, it was found advantageous to file in an extra tooth or two around the front of the saw. At the other end an eye hole attachment was riveted to the blade – a simple ash stick inserted in the eye hole sufficed for a handle.

Frig bobs were probably first used in the late. The sawyer stood or sat directly behind the saw blade which was lined up with the middle of his chest. The saw was held with both hands and the effort shared equally by both arms.

This symmetrical method was not possible when sawing pillar cuts: the arm nearest the pillar had to do more of the work. New pillar cuts were offset by a few inches to give clearance for the saw handle and the sawyer’s hand. This offset is known as a hatch. To prevent chaffing against the pillar, sawyers wrapped a strip of cloth around the knuckles of the hand nearest to the pillar. To avoid the stone breaking off short when it was wristed off it was necessary, when making a pillar cut, to saw to the bottom of the bed without taking a break. Frig bob saw-teeth needed regular sharpening and setting. For sharpening the saw was inserted upside down into a saw cut in the top of a saw stone or bench; the sharpening was done with a triangular file, starting at one end of the saw, filing one side of each tooth in turn with one pass of the file until the other end of the saw was reached. The saw was then turned around and the process repeated on the other side of each tooth. The front angle of the teeth was filed straight across at right angles to the blade.

Repeated sharpening over a long period reduced the depth of a frig bob to around 4 inches (100 mm), this was then known as a razzer or bacon slasher; razzer is believed to be a dialect word meaning worn out. These worn saws had a specialised role for making saw cuts in the jad (the horizontal slot picked out under the ceiling and above the stone being sawn).

The hardness of Bath stone varies between the different beds and quarries; roughly it took an hour to saw a vertical depth of 1 foot over a length of 5 feet or so.

The images below show work in the Box / Corsham area quarries in the 20th century. Whilst not Combe Down, they give a good feel about what it was like to work in the quarries.

Click to enlarge.

[huge_it_gallery id=”19″]Diagrammatic summary of quarrying method

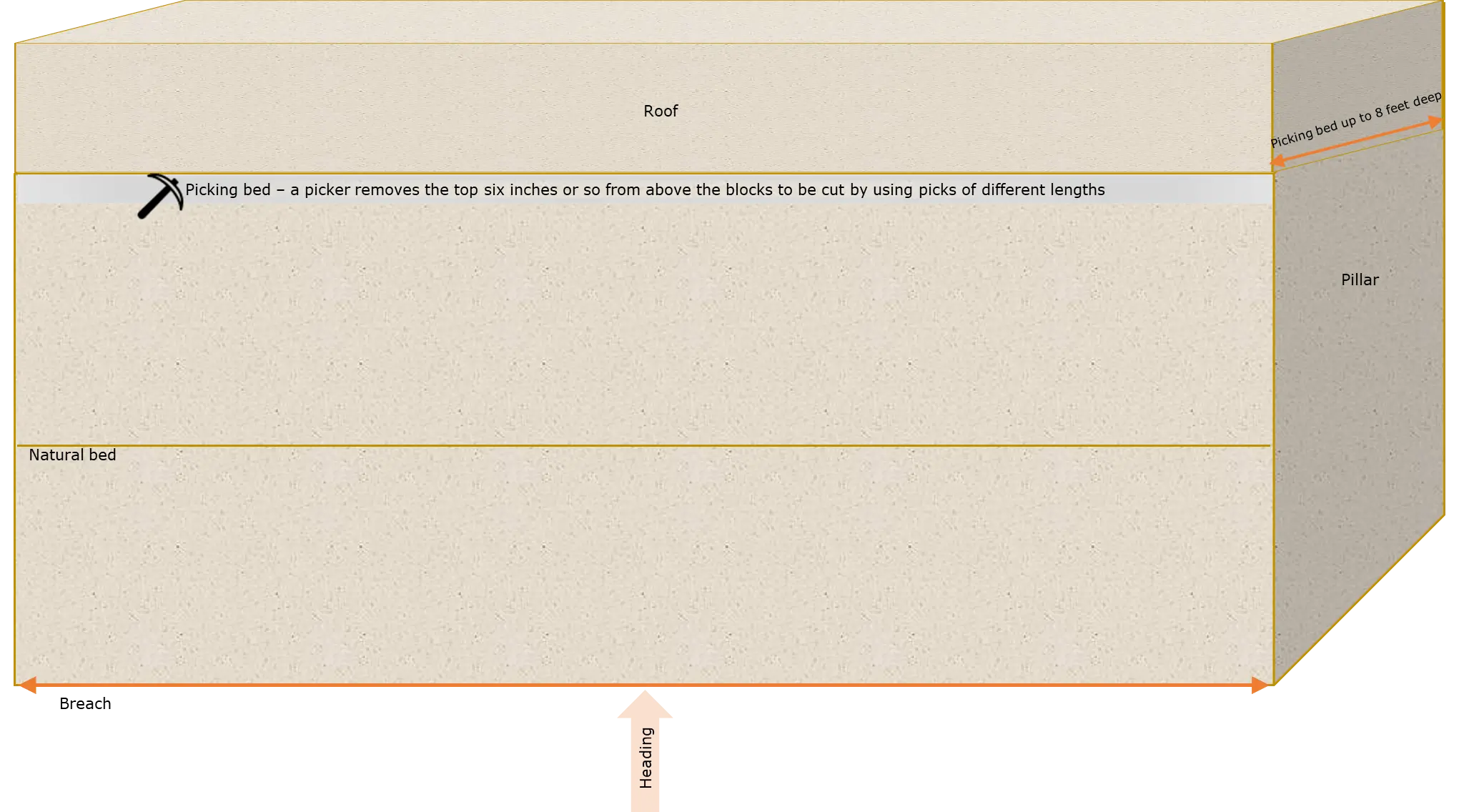

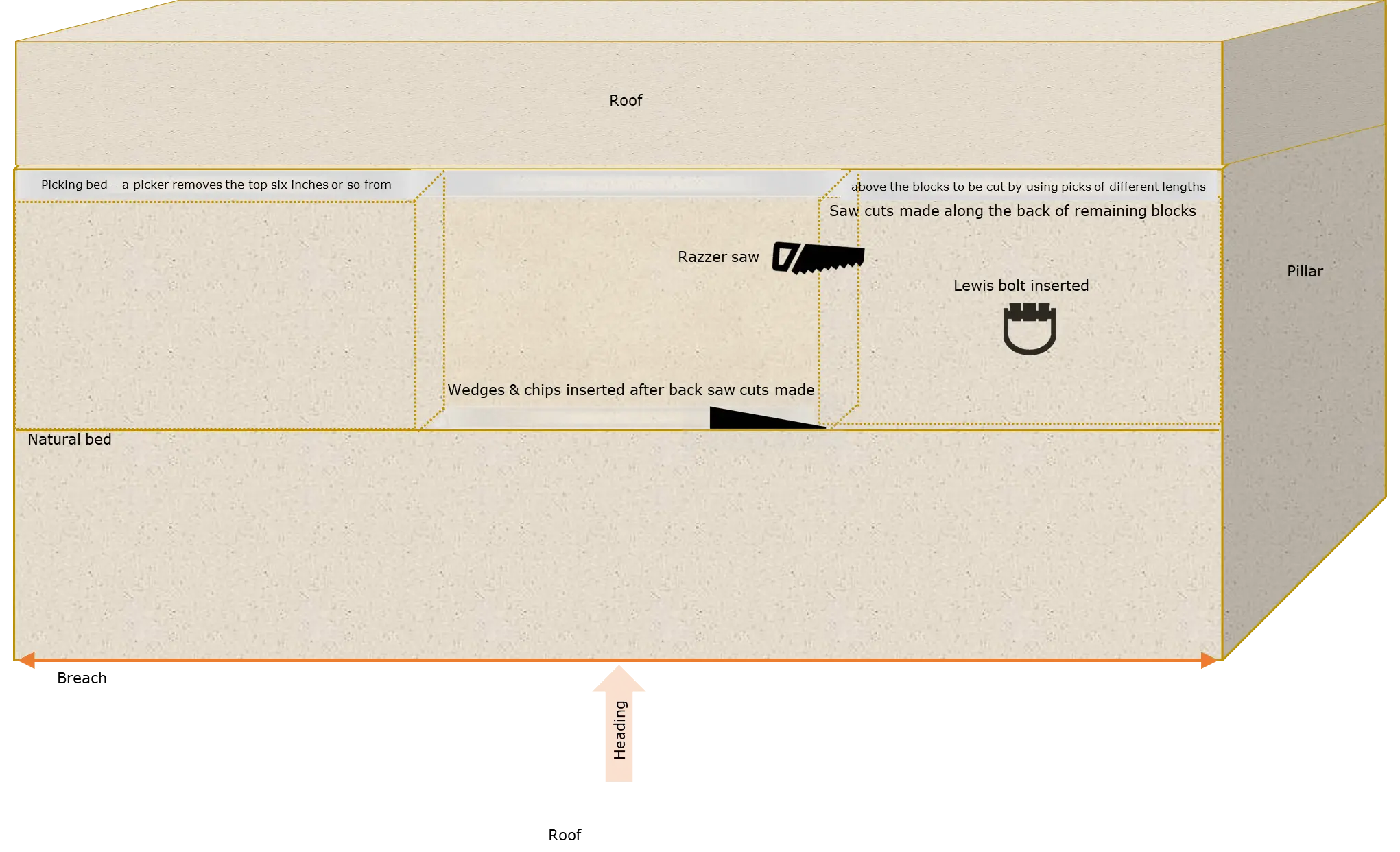

The area to be quarried was marked out at the working face at the end of the heading. Picks of different lengths are used to cut a horizontal slot, called the picking bed, along the top of the bed of stone. This was 6 – 9” deep at the front and about half that at the back. This allowed a saw to be inserted, so that large blocks could be extracted.

Once a slot has been picked out with the pick a long narrow saw, called a razzer, was inserted and a vertical cut started. Once deep enough a much wider saw, called a frig bob, continued to cut down to the base. The wooden handle could be reversed to allow the saw to be used near the roof of an underground quarry. Frig bobs could be eight feet in length and saws were lubricated by water dripping from a can placed on top of the cut. On the Wrist block cuts must be narrower at the back or the block could not be removed. The pillar cut had to be finished without stopping the saw or the pressure from the pillar would break the blocks or jam the saw.

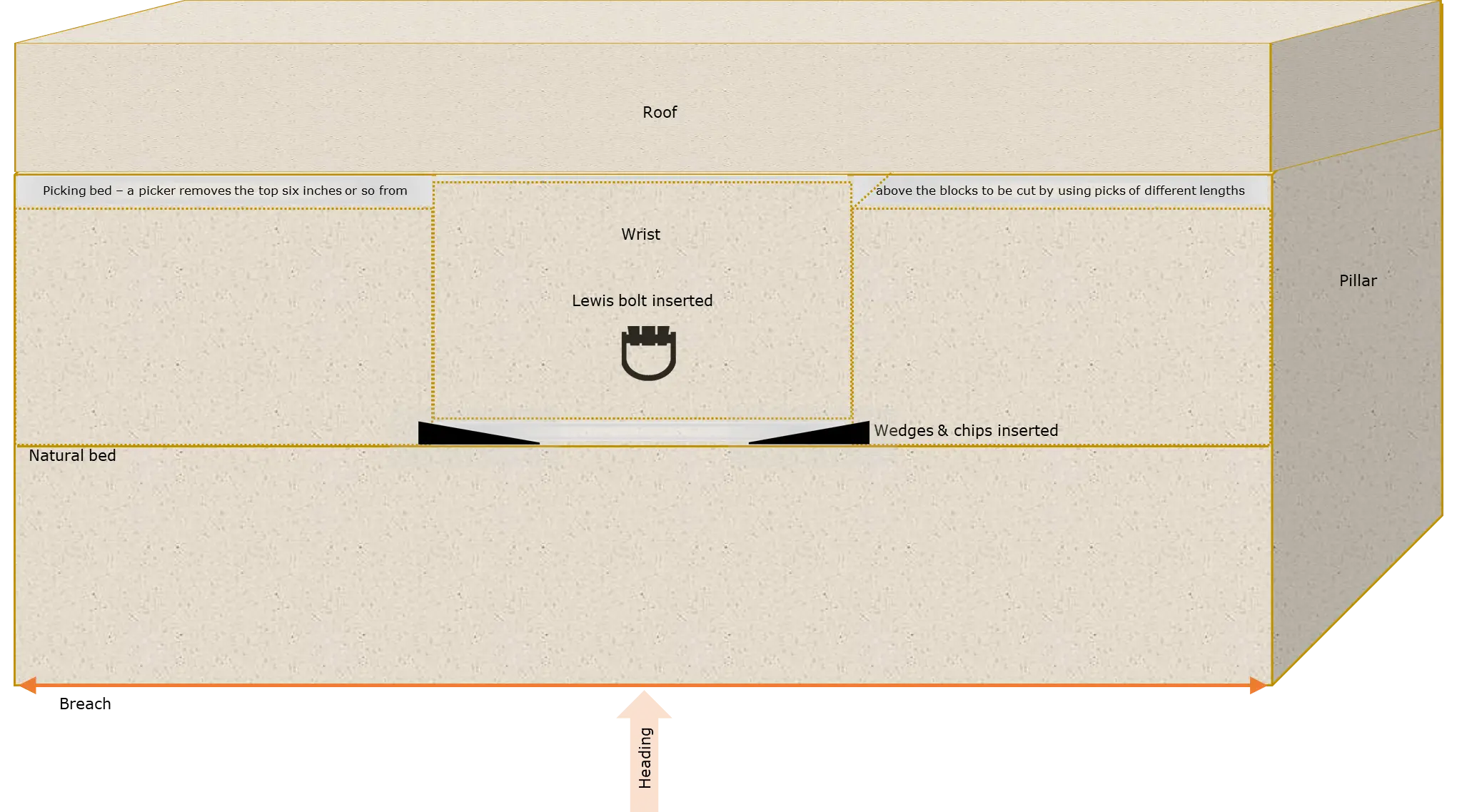

Once the blocks had been sawn, the Wrist was removed by putting a plug and feathers (a wedge and two tapered plates of metal used in reverse, to break the block off the bed) between the beds by hitting them into the stone, forcing the block to break down the back. A Lewis is then fitted into the face of the wrist in a narrow slot cut into block. A crane was fitted to the Lewis via a chain and the crane pulled the chain the pieces of the Lewis were forced to bite into the sides of the slot and it could be hauled out.

Once the Wrist block has been removed the back of the wrist was cleaned with a pick to allow a sawyer with a Razzer to make a cut along the back of the remaining blocks on either side. They would also be broken from their beds by the plug and feathers and removed with a Lewis.

Work starts on the bottom blocks. They would be sawn along the back as well as horizontally and the blocks removed after breaking them off the bed with a handy bar or jump bar.

Glossary of quarry terms

Adit: entrance into a hillside that is nearly horizontal.

Ball: horseshoe shaped iron piece attached to the Lewis pin.

Basket: chaining a block if you cannot get the chain underneath.

Bed: the thickness of each layer of stone based on the natural fault between layers.

Belly: chaining a block by passing it underneath.

Breach: the width worked between two pillars, removed first by the picker.

Breakfast hole: area away from the work used by the quarrymen at meal times.

Brog: nail used to fix rails down to wooden sleepers.

Brogging: hammer for nailing brogs into the sleepers.

Callust: calcite coating deposited by water underground.

Cant: a long end on a block of stone.

Cap or squat block: flat piece of wood placed on top of a prop, between it and roof. allowing a slight amount of downward movement.

Capping: name for the ceiling bed.

Chain: Small = trace, medium= half inch, large= big chain.

Chaps: brown threads running about six inches into the stone.

Chips: two flat pieces of metal inserted with the wedge to create more torque when lifting block from its natural bed.

Chog hole: square hole in ceiling approx. 12 ins. square and 6 to 10 ins. deep, used to hold the crane upright.

Chog: metal sleeve in centre of wood block in ceiling to take the pin from the upright of a hand crane.

Cleats: oak wedges placed in roof joints. In the event of movement these would lock the roof blocks before they could fall.

Cockle: calcite crystals in a hole in the stone.

Crab: like a boatman’s winch. Used with a Lewis and pulley block in the roof to haul hand cranes up into position.

Crane cup: iron cup in the centre of a crane stone.

Crane stone: square hole in floor for the upright of a hand crane to stand in.

Cricks: brown faults going through the stone, usually iron minerals washed in.

Dogs: two-pronged version of a Lewis, usually used to lift blocks in construction of buildings.

Dreadnought: large track mounted chain cutter originally used to cut coal, larger than the Samson.

Drip tin: can with hole and matchstick in, to drip feed water into saw cut.

Fault: large natural fissures in the stone.

Flask basket: two handled straw baskets, hung on files in wall to keep out rats.

Frig bob: long and wide bladed saw used to cut out the blocks.

Ginny / Jinny ring: horse powered windlass used to haul the blocks up shafts.

Gobs: small pieces of waste stone.

Green block: unhardened fresh stone which still has its quarry sap and needs seasoning.

Hand crane: worked by four men, two on each side. Capable of lifting 5 tons.

Handy bar: worked by two or three men, a large crow-bar used to lift bottom stones off their bed.

Hatching: the offset along a pillar between one saw cut and the next.

Heading: direction of a working face.

Helve: wooden handle on pick.

Holing iron: a short iron with a chisel head used to complete Lewis holes.

Jadding iron: long iron rod used to take out the back corners of the breach which could not be reached by the curving swing of the pick. A good picker would not need to use one as he would be able to swing both to right and left.

Jim crow: tool to bend or straighten tramway rails.

Joints: small faults or cracks in the stone.

Jump: a change in level of the beds, i.e. a geological fault.

Jumper or big bar: giant crow bar used to break the blocks away from the beds.

Kivel: the trade mark of Kingston Minerals, a tool with a hammer head opposite a pick head, used in squaring up harder stones, e.g. Portland, but not on Bath Stone which is softer at the time of extraction, hardening on exposure.

Lewis: trapezoid shaped attachment in two or three sections, inserted into tapered holes made in blocks to enable them to be pulled from the face or lifted.

Loading bay: sunken platform near working face where before cranes were introduced blocks could be winch and barred onto the wagons.

Much: waste stone on a block.

Muck box: three-sided metal container for haulage of rubble.

Nips: small version of shears, see below.

Old men: brown faults in all directions.

Opening hammer: used to set the teeth of saws.

Paddy link: link similar in shape to a key-hole, used to make a loop on a chain and hold it without tying.

Pick: Beater pick, for packing sleepers under rails. Holing pick, for making holes for the chips and wedge and commencing Lewis holes. Muck or navvy pick, for breaking up hard rubble. Picking pick, for picking out the roof area before sawing the stone. Roughing pick, for squaring up the block before finishing with a double-headed axe.

Picking or Jad: the bed to be removed at the top.

Pillar cut: cut alongside of the area to become the pillar.

Pillar: area of stone left to support the roof.

Plug and feathers: the plug is a thin long wedge; the feathers, two reverse taper pieces of metal that fit in a hole and the plug is driven between them.

Point: small iron tool for breaking gobs.

Prop / stick: used to support areas of the ceilings.

Qarr: name used by the quarrymen when referring to the quarries.

Quarry sap: natural moisture in the stone when in the ground.

Razzer: tapering saw used to commence cutting until the frig bob could be inserted.

Road: term used for the tracks.

Samson: track mounted chain cutter.

Saw block: block with long slot in used to hold saws while sharpening and re-setting.

Scappled block: block which has been roughly squared up by hand axe.

Scappling: to square a block with a double headed axe.

Scaulter / Scorter: diagonal wooden prop from pillar to roof.

Scriber: tool to scratch number and cubic size on block.

Shears: like large callipers, used for lifting block; spans vary from two feet to eight feet.

Sleighter joint: a clean fault in the stone.

Slipper: sheer sided fault that can be dangerous as there is nothing natural to catch against.

Slope shaft: entrance shaft usually steep.

Squaring: only blocks that have been cleaned and squared will be paid for.

Squats: small stones, one in front and two at the back, put on the trolley before the block is put on it. The squats allow the trolley to rock on bends in the mine roadways. If it were rigid it would derail.

Stacker: movable crane used to stack stone underground in winter.

Stacking ground: area where blocks are seasoned and stored.

Stake: wooden holder for an oil lamp.

Tapper: pebble or piece of metal used to test stone by striking it and listening to the ring. Faults invisible to the eye can thus be traced.

Tapping iron: various length bars with a ball end, used to tap ceiling beds, again the sound tells the condition of the beds.

Trace: chain used to pull block from face instead of a Lewis.

Trolley bar: bar to stop a trolley or to replace it on the rails.

Trolley: mine wagon, sometimes called a bogey cart or wagon.

Wedge: short broad chisel driven in between the chips.

Whim: animal powered winding drum or winch.

Whimmer: like a long brace and bit; used for making blast holes in the days when black powder (gunpowder) was used.

Windy drill: pneumatic drill.

Wood hole: a piece of fossil driftwood in the bed.

Working face: the area where the stone is being removed.

Wrist: first block removed from the heading after making a new set of cuts. The wrist had to be wedged off from the back and when it had been removed a sawyer could squeeze into the narrow space and make back-cuts behind the other blocks.

The quarrymen

Chopper: man who squared up (scappled) the stone using a hand axe.

Dayman: member of the stacking gang in the stock yard.

Gaffer: The owner or boss / manager, pays money to ganger.

Ganger: man responsible for the heading, pays piece work earnings to men.

Picker: man who removed the roof bed, using picks with increasing length of handle.

Roadman: maintained the roadways in the mine.

Sawyer: man who sawed out the blocks. By putting the saws in at an angle on the outer margins of the heading, the sawyer could increase the width of the lower blocks over the size for which the picker had been paid in removing the roof bed. This was known as robbing the picker. It resulted in a downward tapering shape to the pillars left in the mines to support the roof.

Useful reading

Bath Stone a quarry history by J W Perkins, A T Brooks & A E McR Pearce, 1979, ISBN 0-646045-24-0

Bath Stone Quarries by Derek Hawkins, 2011, ISBN 978-0-9654405-4-9

Quarries of England & Wales by Peter Stanier, 1995, ISBN 0-906294-33-9

Stone Quarry Landscapes by Peter Stanier, 2000, ISBN 0-7524-1751-7

The Fashionable Stone by Kenneth Hudson, 1971, SBN 239-00066-8